Today, 42 years ago, we had the great pleasure of discovering the reality of 5-fold crystals.

On the morning of 8 April 1982, an image counter to the laws of nature appeared in Dan Shechtman’s electron microscope. In all solid matter, atoms were believed to be packed inside crystals in symmetrical patterns that were repeated periodically over and over again. For scientists, this repetition was required in order to obtain a crystal.

Shechtman’s image, however, showed that the atoms in his crystal were packed in a pattern that could not be repeated. Such a pattern was considered just as impossible as creating a football using only six-cornered polygons, when a sphere needs both five- and six-cornered polygons. His discovery was extremely controversial. In the course of defending his findings, he was asked to leave his research group. However, his battle eventually forced scientists to reconsider their conception of the very nature of matter.

From “A remarkable mosaic of atoms” – Noble Prize Chemistry, 5 October 2011

Even more interesting was the discovery of 5-fold symmetry in nature by Paul Steinhardt, a physicist whose fields include the gritty physics of matter, a theorist, that is, he uses computers, math, and his brains to make sense of data that the more hands-on experimentalists collect.

But also, he returned some years ago from an expedition to the Koryak mountains in far east Russia, farther east than Siberia, on what he thought was a 1 percent chance that he’d find a rock from outer space containing a forbidden crystal.

He found the rock, and in it was the forbidden crystal.

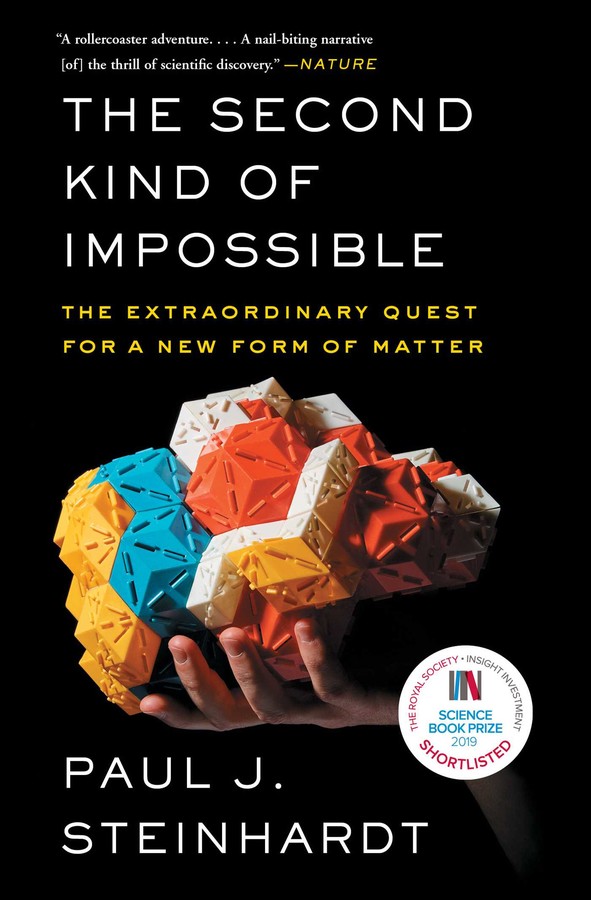

The story is available in a great book, summarized here and discussed by the author in this presentation, available on-line.

It was natural.

Paul Steinhardt

But it was not made on Earth.

It was made in space.

“THE SECOND KIND OF IMPOSSIBLE tells one of the strangest scientific stories that you will ever hear – a thirty-five year quest for new forms of matter, known as quasicrystals, that violate scientific principles that had been established for centuries. The talk describes the scientific odyssey that unfolds over the ensuing decades, first to prove the validity of the idea, and then to pursue Steinhardt’s wildest conjecture: that nature made quasicrystals long before humans discovered them. Along the way, his team encounters clandestine collectors, corrupt scientists, secret diaries, international smugglers, and KGB agents. Their quest culminates in a daring expedition to a distant corner of the Earth, in pursuit of tiny fragments of a meteorite forged at the birth of the solar system.”

Stepping back from our speculations, we must admit that we really do not know whether quasicrystals are rare in the Universe, but the discovery of natural quasicrystals forces us to set aside the historic arguments that suggested they must be. Scientists will learn more as they conduct further searches for natural quasicrystals and perform the experiments they inspire.

Are quasicrystals really so rare in the Universe? – Outlooks in Earth and Planetary Materials, 2020

Paul Steinhardt says that the quasicrystal is a new phase of matter which not only formed naturally but also was also one of the first the solar system formed. He says, his hope all along has been “to find something nature made that we didn’t know it could make.

Key takeaway for me is:

Do not exclude options, even if they are not obvious.

Nature has more to offer than what we observe or expect.