Adam Rupe, James P. Crutchfield published “On principles of emergent organization“:

After more than a century of concerted effort, physics still lacks basic principles of spontaneous self-organization. To appreciate why, we first state the problem, outline historical approaches, and survey the present state of the physics of self-organization. This frames the particular challenges arising from mathematical intractability and the resulting need for computational approaches, as well as those arising from a chronic failure to define structure. Then, an overview of two modern mathematical formulations of organization—intrinsic computation and evolution operators—lays out a way to overcome these challenges. Additionally, we show how intrinsic computation and evolution operators combine to produce a general framework showing physical consistency between emergent behaviors and their underlying physics. This statistical mechanics of emergence provides a theoretical foundation for data-driven approaches to organization necessitated by analytic intractability. Taken all together, the result is a constructive path towards principles of organization that builds on the mathematical identification of structure.

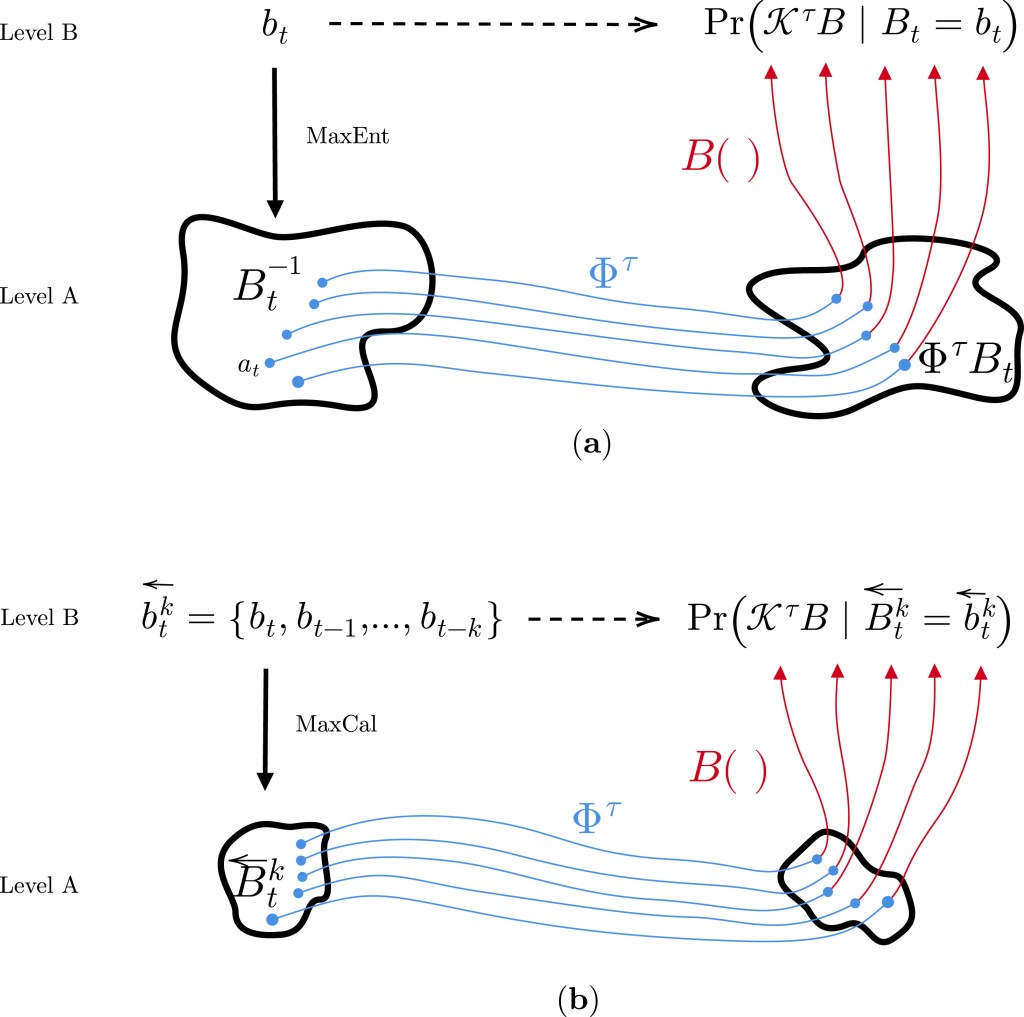

(a) Instantaneous case of a single Level B observation.

(b) History-dependent case of a trajectory of Level B observations.

Historically, principles of organization are given in the constructionist paradigm.

Paraphrasing Feynman, what we now call constructionism is described as: “We look for a new law [principle] by the following process. First, we guess it. Then, we compute the consequences of the guess … to see what it would imply. Then we compare the computation results with experiment or observations”. The nonlinear dynamics bifurcation-theoretic derivation of the critical Rayleigh number that predicts the first onset of Bénard convection cells is a prototypical example that follows Feynman’s dictum. There are limits, however, to constructionism, and so general principles of organization require a new paradigm of understanding for complex systems with emergent behaviors.

For equilibrium, we outlined how the 2nd Law provides a variational organization principle: equilibrium thermodynamic states, including organized states, are those that maximize entropy subject to system constraints.

We described Classical Irreversible Thermodynamics as an attempt to generalize the First and Second Laws of equilibrium thermodynamics to nonequilibrium field theories. However, we showed that the entropy production density and its associated balance equation—the nonequilibrium generalizations of entropy and the 2nd Law—are superfluous at best and, at worst, not physically justified. Indeed, extrema of entropy production do not determine nonequilibrium steady-states, analogous to extrema of entropy determining equilibrium states. Ultimately, empirically-derived phenomenological laws and energy balance—the nonequilibrium generalization of the 1st Law—are used to derive the nonequilibrium transport equations used by nonlinear dynamics’ pattern formation theory.

Prigogine et al.’s theory of dissipative structures claimed to be a thermodynamic theory of pattern formation and self-organization.

After reviewing prior arguments and counterexamples that disproved dissipative structures, we went further to show that certain foundational assumptions from classical irreversible thermodynamics—on which dissipative structures theory is built—are not valid for interacting systems with nonzero levels of organization. Therefore, dissipative structures cannot be a theory of self-organization, as it purported to be. The thermodynamics of pattern formation and spontaneous self-organization thus remains an open problem.

What might a future theory, or principles, of organization look like?

We argued that the standard constructionist paradigm can fail for systems with emergent behavior. Since the intricate organization that forms in far-from-equilibrium systems is emergent, it is no wonder that universal principles of organization have remained elusive within the constructionist paradigm. Analytic intractability and even uncomputability thwart our ability to “compute the consequences” of a proposed mechanistic hypothesis.

A key step forward is to mathematically identify organization. Implicitly, this implies moving beyond simple notions of exact symmetries (and small deviations from them) and beyond subjectively selecting function bases for representational “dictionaries”.

We reviewed two modern approaches to this challenge—evolution operators and intrinsic computation. Both lie outside constructionism, as neither can be analytically computed in general. However, they provide a theoretical framework for data-driven discovery of pattern and organization. Koopman and Perron–Frobenius evolution operators evolve system observables and probability distributions, respectively. Their spectral decompositions can identify statistical organization in time-independent systems, as well as coherent structures that heavily dictate transport in time-dependent systems.

In a complementary way, intrinsic computation decomposes a system into its minimal causal components using predictive equivalence. The semigroup algebra of intrinsic computation identifies organization by generalizing exact symmetries, and its extension to field theories using lightcones can also identify coherent structures.

Completing the relation between evolution operators and intrinsic computation is a challenge currently. It is encouraging that they both converge on their identification of coherent structures. At this time, though, it is not clear whether these two represent two pieces of a larger, universal theory of organization. Whether or not such a universal theory of organization even exists is an open question.

A tantalizing path forward is offered by combining evolution operators with predictive equivalence to formulate a statistical mechanics of emergence. Emergence is what has stymied efforts to develop constructionist principles of organization. The new mathematical tools that directly identify complex forms of organization also come together in a universal theory that provides complete and self-contained dynamics for a higher-Level emergent description of a system that is physically consistent with its lower-Level description. While not analytically constructible in practice, this theory provides a rigorous foundation for data-driven approximation of emergent dynamics through predictive equivalence.

We close with a brief remark on causal mechanism discovery.

While nonequilibrium equations govern transport of energy and matter, different equations—specifically those derived from different phenomenological laws—represent distinct, but equally important mechanisms governing system dynamics. To address emergent behaviors in such broader classes of complex system, the added importance of information transport and related causal mechanisms is increasingly appreciated. Identifying causal mechanisms directly from system behaviors is an active and ongoing area of research.

We once again see the data-driven paradigm to scientific discovery filling the void left by the shortcomings of constructionism for complex systems with emergent behaviors.