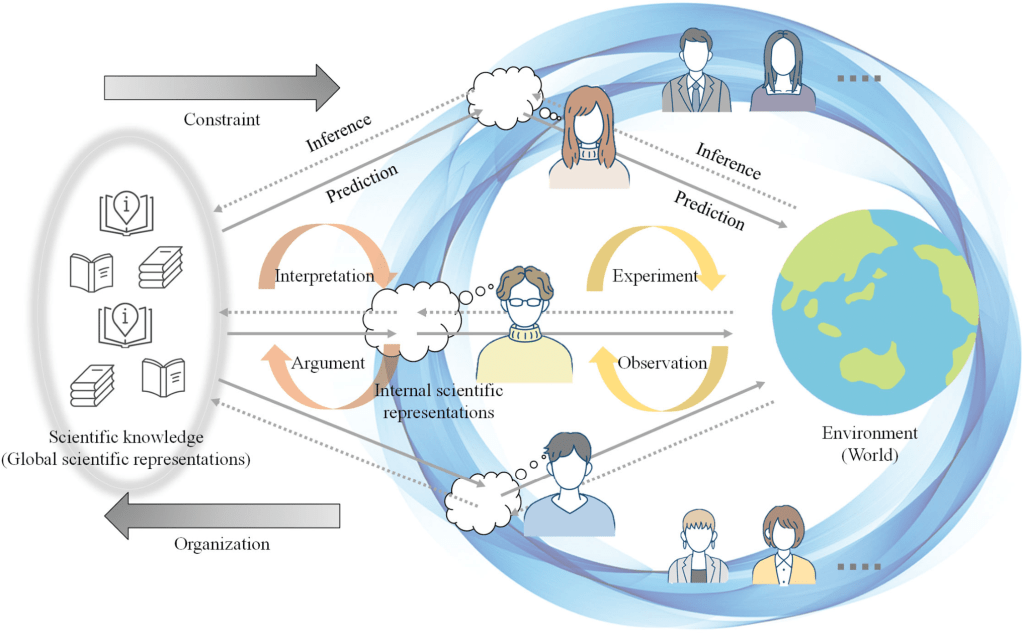

This figure illustrates how scientific knowledge emerges through collective processes. Scientists conduct experiments and observations, engaging with the target objects, i.e. environment, through their research methodologies. These individual interactions generate data and insights, which are then synthesized and encoded into a shared system of scientific knowledge, analogous to how language emerges in linguistic systems. The diagram depicts a cyclical nature of this process, where internal scientific activities contribute to and are informed by the collective understanding, forming a dynamic feedback loop between personal research and the broader scientific corpus.

This article proposes a new conceptual framework called collective predictive coding as a model of science (CPC‑MS) to formalize and understand scientific activities.

Building on the idea of CPC originally developed to explain symbol emergence, CPC‑MS models science as a decentralized Bayesian inference process carried out by a community of agents.

The framework describes how individual scientists’ partial observations and internal representations are integrated through communication and peer review to produce shared external scientific knowledge.

Key aspects of scientific practice like experimentation, hypothesis formation, theory development and paradigm shifts are mapped onto components of the probabilistic graphical model.

This article discusses how CPC‑MS provides insights into issues like social objectivity in science, scientific progress and the potential impacts of artificial intelligence on research.

The generative view of science offers a unified way to analyse scientific activities and could inform efforts to automate aspects of the scientific process. Overall, CPC‑MS aims to provide an intuitive yet formal model of science as a collective cognitive activity.

Scientific activities as collective predictive coding:

From a mathematical perspective, CPC can be modelled using probabilistic graphical models (PGMs) where latent variables representing shared external representations are inferred in a decentralized way through agent interactions and communication. Following figure represents a general form of CPC, ignoring the temporal and dynamic aspects of agent–environment sensory–motor interactions, and focusing on representation learning perspectives. The computational model for CPC was obtained by extending the PGM for individual representation learning to a social one.

CPC hypothesis proposes that language emerges and evolves as a shared representation system that encodes information about the world in a compressed way, allowing agents to align their models of the world.

Left: an integrated model depicting the relationship between individual scientists’ observations and a shared global scientific representation. Right: a decomposed version of the model, illustrating how the global scientific representation wd evolves through inter-scientist communication, acting as a decentralized Bayesian inference.

Causal inference in scientific activities

The current CPC‑MS framework primarily focuses on correlational patterns between observations and internal/external representations within scientific activities.

However, a significant aspect of scientific inquiry involves establishing causal relationships rather than mere correlations—scientists often aim to determine what causes what, not just what predicts what.

While our current formulation captures the predictive aspect of science through the Bayesian inference framework, it does not explicitly address how causal inferences are made or how interventional data (as opposed to observational data) is integrated into the scientific process.

Scientists make causal statements by taking action—by manipulating variables and observing the effects—going beyond inferences about language or symbols. Future extensions of CPC‑MS could incorporate formal causal modelling tools such as causal Bayesian networks, do‑calculus or potential outcomes framework to explicitly represent how scientists form and test causal hypotheses.

This extension would bridge the gap between the current predictive framework and the causal nature of scientific explanation, potentially providing insights into how collective scientific activities establish causal knowledge despite individual limitations in experimentation and observation.

The CPC‑MS framework presented in this article offers a novel perspective on scientific activities, viewing them through the lens of CPC and decentralized Bayesian inference. By modelling science as a generative process carried out by a community of agents—namely, generative science—CPC‑MS provides several key insights.

It formalizes the social nature of scientific knowledge production, demonstrating how individual observations and hypotheses are integrated into explicit scientific knowledge, i.e. global scientific representations, through communication and peer review. The CPC‑MS framework offers a mathematical foundation for understanding scientific progress, paradigm shifts and the role of diversity in scientific communities.

It bridges the gap between individual cognitive processes and collective knowledge creation in science, offering a unified view of scientific activities, from experimentation to theory development.

The CPC‑MS framework aligns with and extends existing ideas in the philosophy of science, such as social objectivity and the generative nature of scientific theories. It encourages us to view science not just as a collection of facts or theories, but as a dynamic, collective cognitive process that continually refines our understanding of the world.