I used to drink it, long time ago, a little bit… coffee.

I’m happy without – and the evidences are being presented more and more.

Coffee consumption decreases the connectivity of the posterior Default Mode Network (DMN) at rest. The obvious clear title of a recent paper.

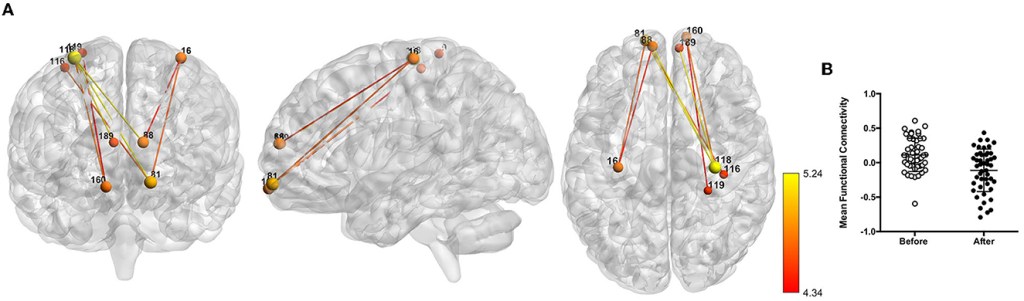

(A) Coronal, sagittal, and axial view of the networks, with connections color-coded from red to yellow according to the statistical strength of the effect.

(B) Box plots representing the before and after coffee consumption average FC

A very readable summary is offered by Frontiers Science News: That essential morning coffee may be a placebo. Scientists testing coffee … found that plain caffeine only partially reproduces the effects of drinking a cup of coffee, activating areas of the brain that make you feel more alert but not the areas of the brain that affect working memory and goal-directed behavior.

“Acute coffee consumption decreased the functional connectivity between brain regions of the default mode network, a network that is associated with self-referential processes when participants are at rest,”

“The functional connectivity was also decreased between the somatosensory/motor networks and the prefrontal cortex, while the connectivity in regions of the higher visual and the right executive control network was increased after drinking coffee. In simple words, the subjects were more ready for action and alert to external stimuli after having coffee.”

The main article states in the conclusions.

Comparing resting-state FC before and after coffee consumption in habitual coffee drinkers, reveals that the connectivity of the posterior DMN is decreased after drinking coffee, while the connectivity in nodes of the higher visual and the right executive control network (RECN) is increased after drinking coffee. Importantly, the decrease in the posterior DMN connectivity is replicated by caffeine intake, whereas the alterations observed in the higher visual and the RECN are not. These observations add to our knowledge of the motivation to drink coffee and disentangle the brain connectivity effects that are attributable to caffeine (posterior DMN), from those that are triggered by other dimensions of coffee intake.

The impact of coffee (and caffeine) on the connectivity of the posterior DMN, namely in the left precuneus. The components of the DMN are known as a cognitive and physiological neurobiological framework necessary for the brain to respond to external stimuli. In particular, the precuneus is a dynamic area of the brain involved in self-consciousness, memory, and visuospatial imagery, functions commonly reported to be altered after coffee intake.

Similarly, coffee and caffeine are well-known to induce wakefulness, and the finding herein reported is noticeable given that the precuneus network is connected to subcortical areas of the reticular activating system implicated in arousal.

Additionally, it is worth noting that the precuneus has emerged as a central node of the DMN and perhaps the most connected hub in the cortex and, therefore, the observation of decreased connectivity after coffee and caffeine intake at rest in this node points to a higher preparedness to switch from resting to task-context processing after coffee intake.

I also want to state some excerpts from a related article coming from the conversation: Nope, coffee won’t give you extra energy. It’ll just borrow a bit that you’ll pay for later

Many of us want (or should I say need?) our morning coffee to give us our “get up and go”.

You might think coffee gives you the energy to get through the morning or the day – but coffee might not be giving you as much as you think.

The main stimulant in coffee is the caffeine. And the main way caffeine works is by changing the way the cells in our brain interact with a compound called adenosine.

Getting busy, getting tired

Adenosine is part of the system that regulates our sleep and wake cycle and part of why high levels of activity lead to tiredness. As we go about our days and do things, levels of adenosine rise because it is released as a by-product as energy is used in our cells.

Eventually adenosine binds to its receptor (parts of cells that receive signals) which tells the cells to slow down, making us feel drowsy and sleepy. This is why you feel tired after a big day of activity. While we are sleeping, energy use drops lowering adenosine levels as it gets shuffled back into other forms. You wake up in the morning feeling refreshed. Well, if you get enough sleep that is.

If you are still feeling drowsy when you wake up caffeine can help, for a while. It works by binding to the adenosine receptor, which it can do because it is a similar shape. But it is not so similar that it triggers the drowsy slow-down signal like adenosine does. Instead it just fills the spots and stops the adenosine from binding there. This is what staves off the drowsy feeling.

No free ride

But there is a catch. While it feels energising, this little caffeine intervention is more a loan of the awake feeling, rather than a creation of any new energy.

This is because the caffeine won’t bind forever, and the adenosine that it blocks doesn’t go away. So eventually the caffeine breaks down, lets go of the receptors and all that adenosine that has been waiting and building up latches on and the drowsy feeling comes back – sometimes all at once.

So, the debt you owe the caffeine always eventually needs to be repaid, and the only real way to repay it is to sleep.

Timing is everything

How much free adenosine is in your system, that hasn’t attached to receptors yet, and how drowsy you are as a consequence will impact how much the caffeine you drink wakes you up. So, the coffee you drink later in the day, when you have more drowsy signals your system may feel more powerful.

If it’s too late in the day, caffeine can make it hard to fall asleep at bedtime. The “half life” of caffeine (how long it takes to break down half of it) is about five hours). That said, we all metabolise caffeine differently, so for some of us the effects wear off more quickly. Regular coffee drinkers might feel less of a caffeine “punch”, with tolerance to the stimulant building up over time.

Caffeine can also raise levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that can make you feel more alert. This might mean caffeine feels more effective later in the morning, because you already have a natural rise in cortisol when you wake up. The impact of a coffee right out of bed might not seem as powerful for this reason.

If your caffeinated beverage of choice is also a sugary one, this can exacerbate the peak and crash feeling. Because while sugar does create actual energy in the body, the free sugars in your drink can cause a spike in blood sugar, which can then make you feel tired when the dip comes afterwards.

While there is no proven harm of drinking coffee on an empty stomach, coffee with or after a meal might hit you more slowly. This is because the food might slow down the rate at which the caffeine is absorbed.

Caffeine can be useful, but it isn’t magic. To create energy and re-energise our bodies we need enough food, water and sleep.