“When expert predictions fail“ examines the opportunities and challenges of expert judgment in the social sciences, scrutinizing the way social scientists make predictions.

While social scientists show above-chance accuracy in predicting laboratory-based phenomena, they often struggle to predict real-world societal changes.

Most causal models used in social sciences are oversimplified, confuse levels of analysis to which a model applies, misalign the nature of the model with the nature of the phenomena, and fail to consider factors beyond the scientist’s pet theory.

Taking cues from physical sciences and meteorology, we advocate an approach that integrates broad foundational models with context-specific time series data. This article calls for a shift in the social sciences towards more precise, daring predictions and greater intellectual humility.

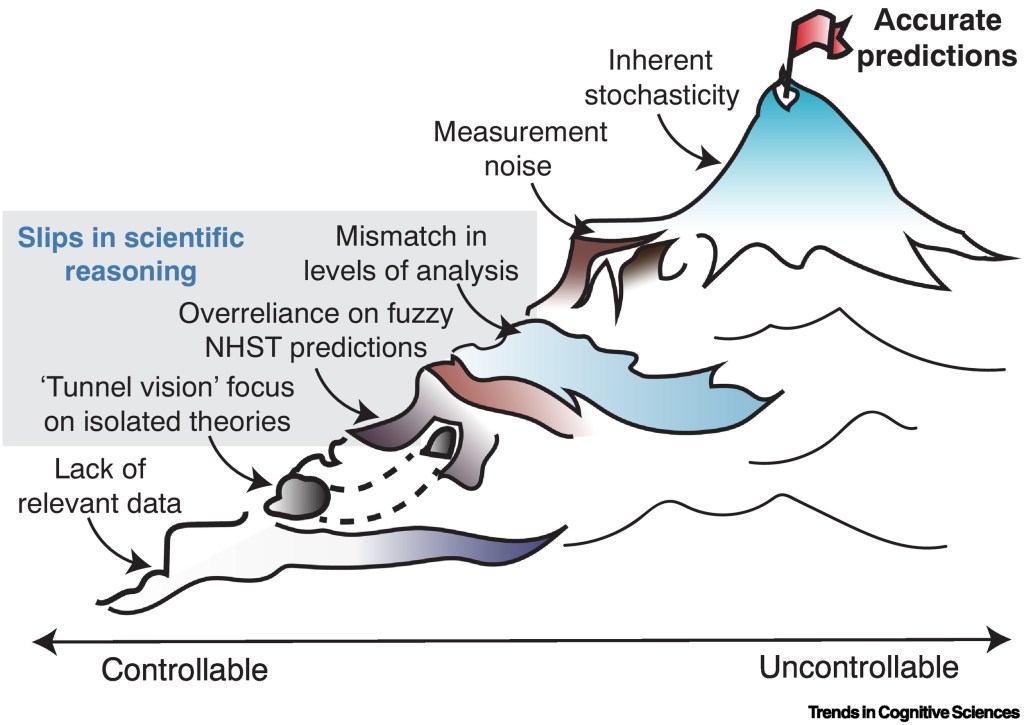

While some sources of inaccuracy are inherently impossible to overcome, others stem from a variety of common slips in scientific reasoning, resulting in poor or no accuracy. (NHST : Null-hypothesis significance testing)

- Unlike in controlled settings, social scientists’ performance when predicting real-world societal trends is indistinguishable from that of laypeople or naive statistical methods.

- There is no conclusive evidence that domain-specific expertise improves predictive accuracy of societal change.

- Causal models in social sciences are oversimplified, confusing levels of analysis, and generally lack specificity about the magnitude or distribution of effects, limiting prediction accuracy.

- Engaging in counterfactual thought experiments to go beyond the most obvious factors specified in a theory, predictive accuracy in social sciences can be improved.

- Integrating broad foundational models with context-specific time series data, as in meteorology, can enhance the accuracy of social science predictions.

- Enhancing analytical training and understanding of temporal dynamics can yield more precise, riskier predictions, the practical application of which requires the fostering of intellectual humility in scientists.

Predictions at the right level of analysis?

The first crucial point to consider is the alignment of your prediction to the correct level of analysis.

The first error, the fallacy of composition (also known as the reversed ecological fallacy), confuses societal and individual-level effects. This error lies in equating what applies to the whole (society) with what applies to the parts (individual differences).

The second error is the conflation of causal models for between-unit differences with those for within-unit changes. In other words, researchers may be led astray by assuming that the conditions affecting variations between different individuals or groups can be directly applied to understand changes within individuals or groups over time, which requires statistical conditions referred to as ergodicity. This presumes a statistical equivalence across individuals and over time that rarely occurs in dynamic social phenomena.

A transformative shift towards a predictive social science necessitates not only the reshaping of our existing models but also the nurturing of future scientists. They should be trained to appreciate computational precision, to have the bravery to embrace riskier predictions, and to cultivate the intellectual humility to concede when they are incorrect.

The existing incentive structures should be redesigned to reward these values.

The predictive power of simulation-based computational models

How can social scientists bypass the pitfalls of prediction, such as levels-of-analysis misalignment and the need for predictions that go beyond directional hypotheses? One solution may be simulation-based computational modeling approaches. Simulation-based computational models rely on mathematical and computational formalisms to implement causal models in code. Successful examples include computational models of learning and decision-making and agent-based models (ABMs) of collective behavior.

Several features of these models make them compelling tools for the improvement of social science predictions.

(i) Explicit level of analysis: Computational models force researchers to make explicit often-implicit assumptions.

(ii) Magnitude and distributional predictions: Computational models usually yield precisely quantifiable predictions.

(iii) Counterfactuals and causal combinations: It is also straightforward to add assumptions from additional causal models and to examine how model dynamics change under different conditions. Simulations can thus provide a formal evaluation of the likely impact of different counterfactuals.

(iv) Specification of necessary data: The existence of a computational model often clarifies the type of data required to generate and test its predictions, facilitating rapid model improvement through accepted model comparison approaches.

One response to “Expert Predictions Fail …”

[…] humble and show the needed intellectual humility, to avoid failure, allowing “playful” decision making, to support the missions defined, and be […]

LikeLike