In following, I resume 3 recent articles on this most valuable topic, related to the survival of our environment, societies and species.

Why the world cannot afford the rich

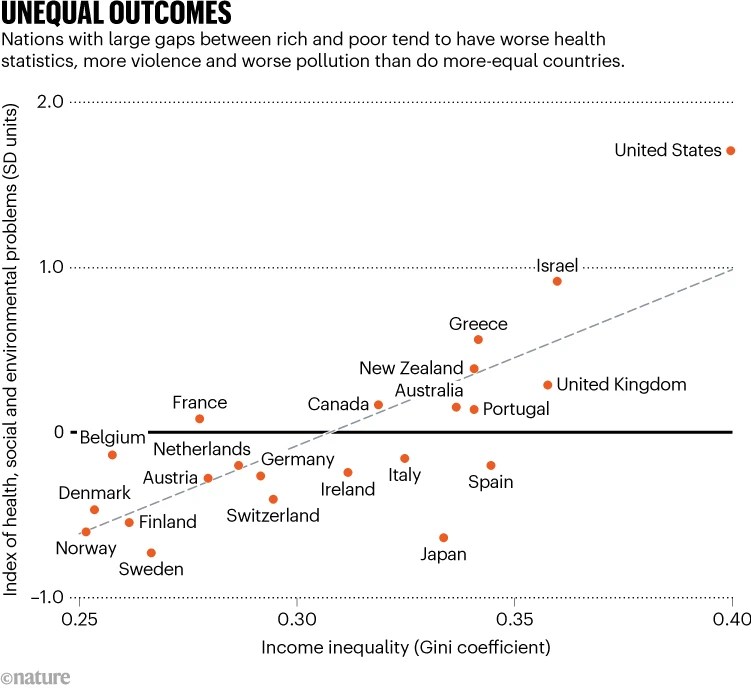

Equality is essential for sustainability.

The science is clear — people in more equal societies are more trusting and more likely to protect the environment than are those in unequal, consumer-driven ones.

The costs of inequality are also excruciatingly high for governments.

For example, the Equality Trust, a charity based in London estimated that the United Kingdom alone could save more than £100 billion ($126 billion) per year if it reduced its inequalities to the average of those in the five countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that have the smallest income differentials — Denmark, Finland, Belgium, Norway and the Netherlands. And that is considering just four areas:

– greater number of years lived in full health,

– better mental health,

– reduced homicide rates and

– lower imprisonment rates.

Many commentators have drawn attention to the environmental need to limit economic growth and instead prioritize sustainability and well-being.

Inequality also increases consumerism.

Perceived links between wealth and self-worth drive people to buy goods associated with high social status and thus enhance how they appear to others — as US economist Thorstein Veblen set out more than a century ago in his book The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899).

Studies show that people who live in more-unequal societies spend more on status goods.

Oxfam reports that, on average, each of the richest 1% of people in the world produces 100 times the emissions of the average person in the poorest half of the world’s population.

That is the scale of the injustice. As poorer countries raise their material standards, the rich will have to lower theirs.

Inequality also makes it harder to implement environmental policies. Changes are resisted if people feel that the burden is not being shared fairly. For example, in 2018, the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) protests erupted across France in response to President Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to implement an ‘ecotax’ on fuel by adding a few percentage points to pump prices. The proposed tax was seen widely as unfair — particularly for the rural poor, for whom diesel and petrol are necessities… Similarly, Brazilian truck drivers protested against rises in fuel tax in 2018, disrupting roads and supply chains.

More-equal societies are more cohesive, with higher levels of trust and participation

… more equal societies are more cohesive, with higher levels of trust and participation in local groups.

The scientific evidence is stark that reducing inequality is a fundamental precondition for addressing the environmental, health and social crises the world is facing. It’s essential that policymakers act quickly to reverse decades of rising inequality and curb the highest incomes.

– First, governments should choose progressive forms of taxation, which shift economic burdens from people with low incomes to those with high earnings, to reduce inequality and to pay for the infrastructure that the world needs to transition to carbon neutrality and sustainability.

– International agreements to close tax havens and loopholes must be made.

– Legislation and incentives will also be needed to ensure that large companies — which dominate the global economy — are run more fairly.

Reducing economic inequality is not a panacea for health, social and environmental problems, but it is central to solving them all. Greater equality confers the same benefits on a society however it is achieved. Countries that adopt multifaceted approaches will go furthest and fastest.

Do billionaire philanthropists skew global health research?

Personal priorities are often trumping real needs and skewing where charitable funding goes.

Book review of “The Bill Gates Problem: Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire” by Tim Schwab.

Global wealth, power and privilege are increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few hyper-billionaires. Some, including Microsoft founder Bill Gates, come across as generous philanthropists. But, as investigative journalist Tim Schwab shows in his latest book, charitable foundations led by billionaires that direct vast amounts of money towards a narrow range of selective ‘solutions’ might aggravate global health and other societal issues as much as they might alleviate them.

In The Bill Gates Problem, Schwab explores this concern compellingly with a focus on Gates, who co-founded the technology giant Microsoft in 1975 and set up the William H. Gates Foundation (now the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) in 1994. The foundation spends billions of dollars each year (US$7 billion in 2022) on global projects aimed at a range of challenges, from improving health outcomes to reducing poverty — with pledges totalling almost $80 billion since its inception.

Schwab offers a counterpoint to the prevailing popular narrative, pointing out how much of the ostensible generosity of philanthropists is effectively underwritten by taxpayers.

Schwab traces the origins of this ‘Gates problem’ to the 1990s. At that time, he writes, Gates faced hearings in the US Congress that challenged anti-competitive practices at Microsoft and was lampooned as a “monopoly nerd” in the animated sitcom The Simpsons for his proclivity to buy out competitors. By setting up the Gates foundation, he pulled off a huge communications coup — rebranding himself from an archetypal acquisitive capitalist to an iconic planetary saviour by promoting stories of the foundation’s positive impact in the media.

Schwab often implies that Gates’s altruism is insincere and rightly critiques the entrepreneur’s self-serving “colonial mindset”. But in this, Gates is a product of his circumstances. As Schwab writes, “the world needs Bill Gates’s money. But it doesn’t need Bill Gates”. Yet maybe the real problem lies less in the man than in the conditions that produced him. A similar ‘tech bro’ could easily replace Gates.

Perhaps what is most at issue here is not the romanticized intentions of a particular individual, but the general lack of recognition for more distributed and collective political agency.

And more than any single person’s overblown ego, perhaps it is the global forces of appropriation, extraction and accumulation that drive the current hyper-billionaire surge that must be curbed.

Resolution of the Bill Gates problem might need a cultural transformation.

Emphasis on equality, for instance, could be more enabling than billionaire-inspired idealizations of superiority.

Respect for diversity might be preferable to philanthropic monopolies that dictate which options and values count.

Precautionary humility can be more valuable than science-based technocratic hubris about ‘what works’.

Flourishing could serve as a better guiding aim than corporate-shaped obsessions with growth.

Caring actions towards fellow beings and Earth can be more progressive than urges to control.

If so, Schwab’s excellent exposé of hyper-billionaire ‘myths’ could yet help to catalyse political murmurations towards these more collective ends.

To build a better world, stop chasing economic growth

The year 2024 must be a turning point for shifting policies away from gross domestic product and towards sustainable wellbeing.

Design better measures of societal well-being

Hundreds of indicators of societal well-being are already in use. Examples include the Genuine Progress Indicator; the OECD Better Life Index; and annual surveys of life satisfaction. To become a societal goal used by all, and to displace GDP, the world must settle on a new indicator. Broad consensus is needed on what should be included.

For example, it is not just income that matters, but also the ways in which it is distributed.

The costs of environmental and social degradation must be included, as should contributors to well-being that are unconnected to income — such as our relationships and communities, good governance, the ability to participate in decision-making and ecosystem services provided by the natural environment. Several research initiatives are beginning to address these issues (including MERGE, which is funded by the European Union).

Constructing a sustainable world where well-being is prioritized must be a key goal for 2024 and beyond

People often fear that such transformations will require sacrifices. In the short term, change is difficult, and addictions are powerful.

But in the long run, it is a huge sacrifice of our personal and societal well-being to continue down the business-as-usual path. Sustainable well-being can improve the lives of everyone, and protect the biodiversity and ecosystem services on which we all depend.

In the coming year, let’s continue to build the shared vision of the world we all want, and accelerate progress towards it.

One response to “Equality is essential for sustainability.”

[…] This approach is still valuable, since the intelligent life of humans and their societies are facing many challenges, not unknown to mankind, but still lacking appropriate action. […]

LikeLike