This paper introduces a model of collective behavior, proposing that individual members within a group, such as a school of fish or a flock of birds, act to minimize surprise. This active inference approach naturally generates well-known collective phenomena such as cohesion and directed movement without explicit behavioral rules. This model reveals intricate relationships between individual beliefs and group properties, demonstrating that beliefs about uncertainty can shape collective decision-making accuracy. As agents update their generative model in real time, groups become more sensitive to external perturbations and more robust in encoding information.

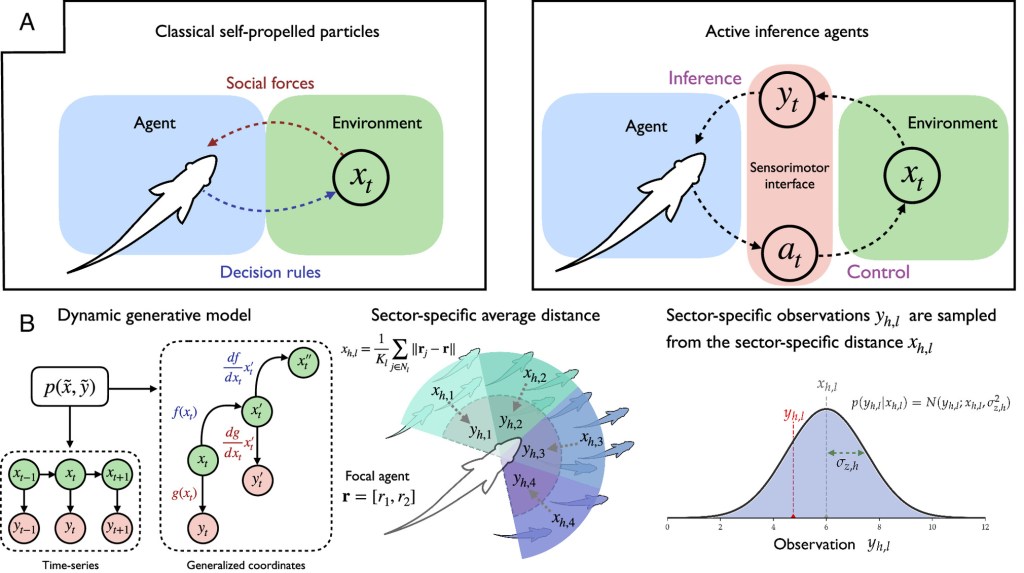

(B) Schematic illustration of the sector-specific distance tracking. The Left panel shows a Bayesian network representation of a dynamic generative model

Collective motion is ubiquitous in nature; groups of animals, such as fish, birds, and ungulates appear to move as a whole, exhibiting a rich behavioral repertoire that ranges from directed movement to milling to disordered swarming. Typically, such macroscopic patterns arise from decentralized, local interactions among constituent components (e.g., individual fish in a school). Preeminent models of this process describe individuals as self-propelled particles, subject to self-generated motion and “social forces” such as short-range repulsion and long-range attraction or alignment. However, organisms are not particles; they are probabilistic decision-makers.

This paper introduces an approach to modeling collective behavior based on active inference. This cognitive framework casts behavior as the consequence of a single imperative: to minimize surprise.

We demonstrate that many empirically observed collective phenomena, including cohesion, milling, and directed motion, emerge naturally when considering behavior as driven by active Bayesian inference—without explicitly building behavioral rules or goals into individual agents.

Furthermore, we show that active inference can recover and generalize the classical notion of social forces as agents attempt to suppress prediction errors that conflict with their expectations. By exploring the parameter space of the belief-based model, we reveal nontrivial relationships between the individual beliefs and group properties like polarization and the tendency to visit different collective states.

We also explore how individual beliefs about uncertainty determine collective decision-making accuracy.

Finally, we show how agents can update their generative model over time, resulting in groups that are collectively more sensitive to external fluctuations and encode information more robustly.

The results shown in the current work serve primarily as a proof of concept: we started by writing down a specific, hypothetical active inference model of agents engaged in group movement, and then generated naturalistic behaviors by integrating the resulting equations of motion (i.e., free energy gradients) for this particular model. Taking inspiration from fields like computational psychiatry, we emphasize the ability to move from simple forward modeling of behavior to data-driven model inversion, whereby one hopes to infer the values of parameters that best explain empirical data (of e.g., behavioral movement data). Instead of using “force mapping” techniques to estimate social forces from behavioral measurements, our approach would instead frame the problem as one of computational phenotyping, where alternative generative models that a particular animal might be equipped with, could be estimated from behavioral or neural data acquired from that animal. The resulting social forces or interaction rules would then emerge as those behaviors that minimize surprise, relative to the generative model that best explains the animal’s behavior. Both the estimation of model parameters and alternative model structures can be achieved through Bayesian model inversion and system identification methods like Bayesian model selection, averaging, or reduction.