Chronic psychosocial stress increases disease risk and mortality, but the underlying mechanisms remain largely unclear. This article in Psychoneuroendocrinology outlines an energy-based model for the transduction of chronic stress into disease over time. The energetic model of allostatic load (EMAL) emphasizes the energetic cost of allostasis and allostatic load, where the “load” is the additional energetic burden required to support allostasis and stress-induced energy needs.

Living organisms have a limited capacity to consume energy.

Overconsumption of energy by allostatic brainbody processes leads to hypermetabolism, defined as excess energy expenditure above the organism’s optimum. In turn, hypermetabolism accelerates physiological decline in cells, laboratory animals, and humans, and may drive biological aging.

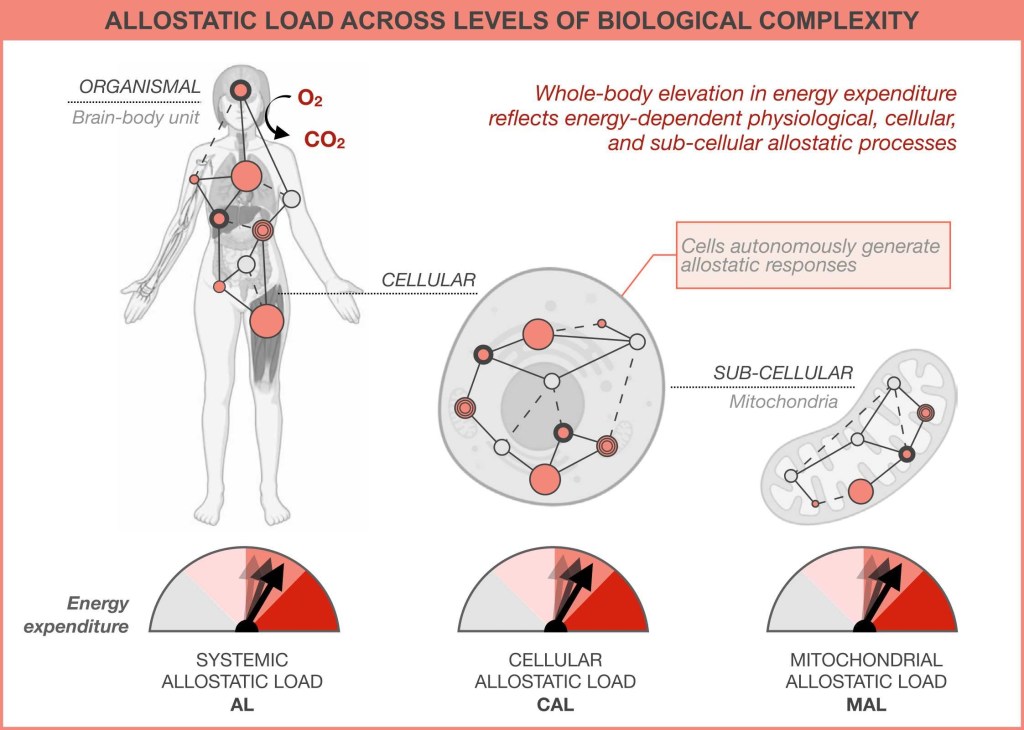

Therefore, we propose that the transition from adaptive allostasis to maladaptive allostatic states, allostatic load, and allostatic overload arises when the added energetic cost of stress competes with longevity-promoting growth, maintenance, and repair. Mechanistically, the energetic restriction of growth, maintenance and repair processes leads to the progressive wear-and-tear of molecular and organ systems. The proposed model makes testable predictions around the physiological, cellular, and sub-cellular energetic mechanisms that transduce chronic stress into disease risk and mortality. We also highlight new avenues to quantify allostatic load and its link to health across the lifespan, via the integration of systemic and cellular energy expenditure measurements together with classic allostatic load biomarkers.

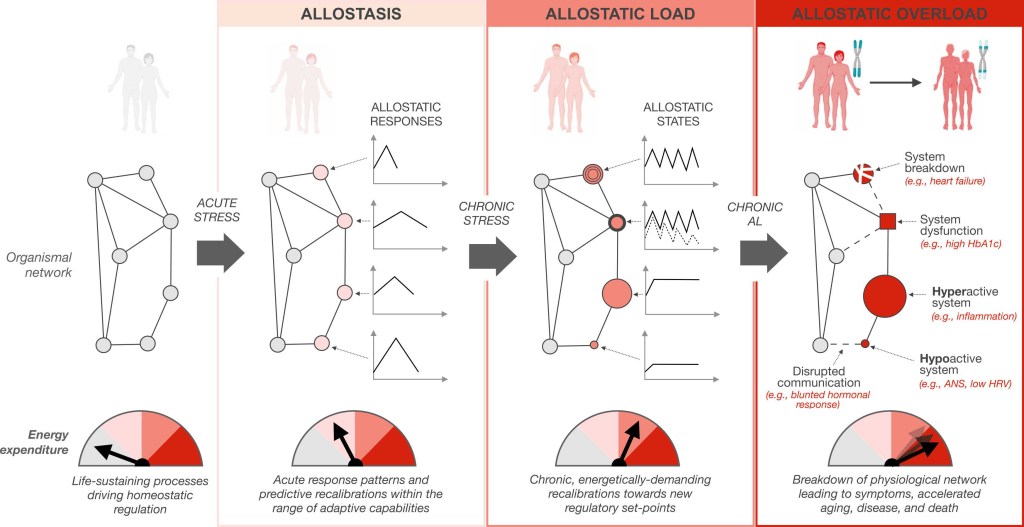

Real or imagined stressors trigger an energy dependent cascade progressing from adaptive allostasis to allostatic states and allostatic load, to allostatic overload, ultimately manifesting as an increased disease risk and accelerated rate of aging. The physiological network, illustrated as nodes and edges, depicts the constant communication (edges) between cells, tissues, organs, and systems (nodes) within the human body under the influence of biopsychosocial and environmental forces. The change in appearance of nodes illustrates the dysfunction, breakdown, and hypo- and hyper-activation of organ systems in response to allostatic load and overload. Dashed lines illustrate impaired communication between organ systems. These changes manifest as measurable circulating biomarkers that eventually become clinical signs and symptoms.

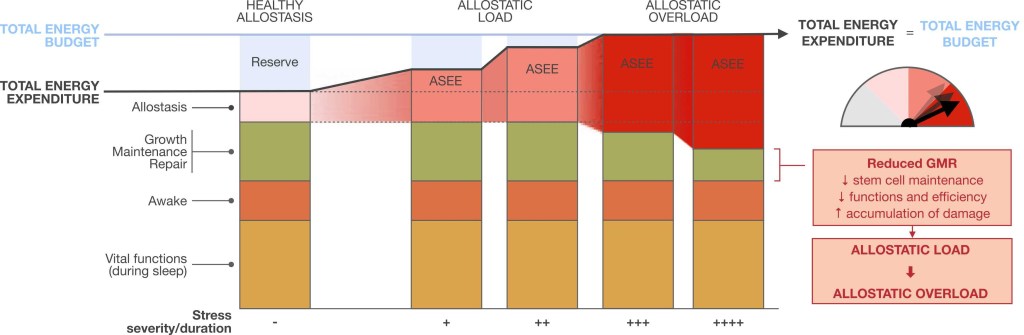

This figure illustrates the effects of stress-induced allostasis on the partitioning of energy costs within the organism, and the transition from allostasis to allostatic load and overload. Real or imagined stressors increase allostasis and stress-induced energy expenditure (ASEE), which consumes the reserve portion of the organism’s total energy budget. When this excess energetic cost exceeds the reserve capacity, it impinges on growth, maintenance, and repair (GMR) processes that are required to sustain health and prevent the entropic decay of cells and systems. As a result, the compression of available resources constrains GMR processes, accelerating the decay of structures leading to allostatic overload marked by the ‘wear-and-tear’ of cellular and physiological systems. Taken together, allostatic load and allostatic overload arise when the energetic costs of stress-induced allostasis supersede or the organism’s available energetic reserve, or when they are prioritized over GMR owing to some other evolutionary mechanism.

The added energetic cost and biological ‘wear-and-tear’ that brain-body allostatic states impose on the organism during chronic stress is a more complex expression of the same process that also take place in cells, and in sub-cellular organelles, such as the energy-transforming mitochondria.

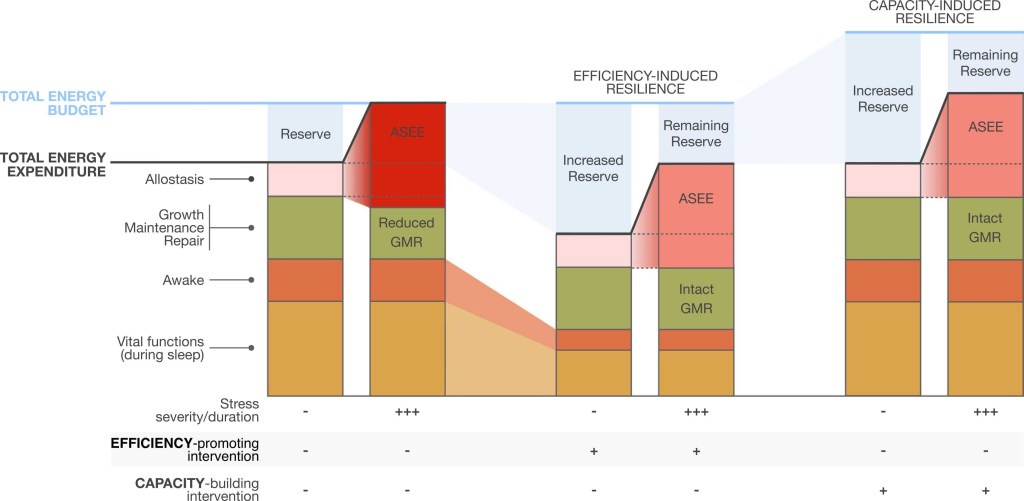

Illustrated are two types of hypothetical scenarios for resilience-promoting interventions. Compared to the situation (left) where allostasis and stress-induced energy expenditure (ASEE) bankrupts the total energy budget and steals energy from growth, maintenance and repair (GMR), resilience to the same stressor can arise from either a reduction in basal metabolic costs (metabolic compensation, middle) or increase the total energy budget (right).

The shifting of the threshold for allostatic overload can increase the ability of the organism to tolerate chronic stress with less of the damaging effects of allostatic overload.

If the EMAL is (partially) correct, it should be possible to demonstrate that chronic stress is damaging because it increases the cost of living or steals energy from GMR processes. A translational combination of cellular, animal, and human studies will be required to fully examine and refine portions of the model. If validated in humans, there would be direct implications for the design of health-promoting and resilience-building interventions.

For example, a new class of interventions could be designed with the explicit goal to reduce the adverse effects of stress by directly targeting energy expenditure. The therapeutic goal would be to prevent hypermetabolism or promote “normometabolism”. A successful outcome would consist of optimizing metabolic efficiency during daily life and upon stress exposure. For example, in the intensive care unit setting – a naturally stressful environment where hypermetabolism predicts mortality – using energy expenditure to design individualized care improved patient outcomes. Energy expenditure, we argue, represents a more integrative, and possibly more accurate, measure of optimal physiological functions than individual molecular markers can reflect. The EMAL suggests that incorporating measures of energy expenditure and metabolic efficiency could increase the sensitivity and specificity afforded by approaches focused on traditional organ-specific allostatic biomarkers. This could in turn help to evaluate the effectiveness of existing interventions in reducing allostatic load, or the magnitude of physiological dysregulation more generally.

The energetic model of allostatic load (EMAL) to account for the stress-disease cascade in humans.

Every biological process costs energy.

Consequently, the anticipatory allostatic processes induced by real and imagined threats consume the organism’s limited energetic resources. Because of evolutionary-acquired cellular and physiological energy constraints, allostasis and stress-induced energy expenditure can divert energy away from GMR processes.

Thus, we propose that the physiological transition between adaptive allostasis and maladaptive allostatic load is the point at which stress-induced energy costs compete with health-sustaining and longevity-promoting growth, maintenance, and repair.

The proposed model opens several testable questions regarding the energetic basis of resilience or susceptibility to stress. Studies specifically designed to test these hypotheses should examine, beyond current models based exclusively on molecular biomarkers, how much added value sensitive and specific measures of energy expenditure contribute to predict meaningful health outcomes. Empirically, these measures could be applied at both the (sub)cellular and whole-body levels, leveraging approaches from both mitochondrial science and human energetics. Importantly, an energetic understanding of the allostatic load theory and of the stress-disease cascade emphasizes the interplay of mind and body processes, and how their interactions rely on energy to survive and thrive across the lifespan.