The article “Getting Things Right; Diagnose and Design in The Evolution of Community Provisioning Systems” tackle the great questions behind the observation of “Why do some governments, organisations and community leaders seem to get it wrong in confronting a crisis?” Why do others succeed? Is there something to be learned from how the different responses came to be so?

For most individuals, organisations and governments, it is

– the tensions that emerge between authoritarian regulatory control and small group independent self-organization, and

– between simple and complex choices in collective decision making,

that present the most difficulties for a shared future.

The hoped for outcomes do not always follow the choices made, highlighting the unpredictability of such complex crises.

Consequently, drawing on macromarketing, marketing systems and human social evolution, we consider how to avoid failure or collapse, enhance quality of life for all, foster insights into community flexibility and resilience, whilst continually shaping over time and space our social, economic, political and environmental systems.

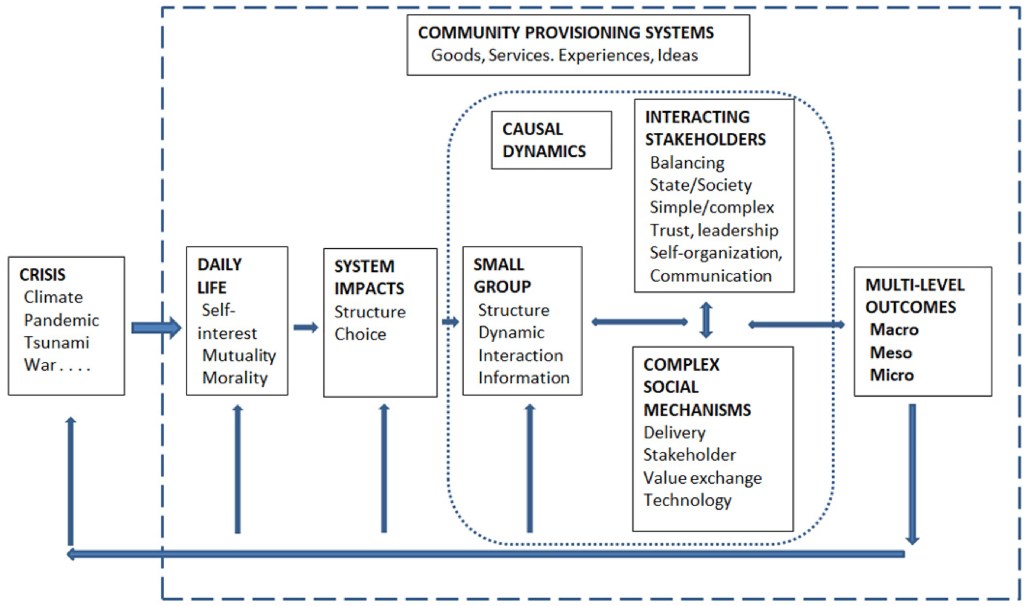

Applying a provisioning systems lens quickly shifts the attention to the causal dynamic impacts of the provisioning systems that every community self-organizes to meet their needs and wants. The performance of the complex social mechanisms involved in the workings of a provisioning system comes into question. The consequences may be that delivery systems collapse, stakeholders disintegrate into disagreement and sometimes conflict, technology evolution is challenged to fill emerging gaps, and the community blend of self-interest, mutuality and morality values are often threatened and subject to rethinking. It is these evolutionary dynamics in communities, small and large, traditional or developed, remote or central, which provides the settings for provisioning systems. The evolutionary dynamics of provisioning systems are critical challenges for macromarketing scholars, for policy makers and managers and for external influencers, at a time when effective intervention in response to crisis is a high priority in most communities.

A first mapping of the issues involved.

An essential part of the social reconstruction of a community is the re-emergence of the provisioning systems. That is the social systems and structures that make possible the sourcing, supply and consumption of the ever-changing set of goods, services, experiences and ideas that people in a community need and want.

This re-emergence is a social process, reflecting both top-down initiatives and bottom-up, self-organized, experimental collaborations; combining helping hands with innovation, and opportunistic market exchanges as individuals, groups and entities work together to fill an almost endless series of gaps and possibilities.

It takes time, often more than expected, to do what is needed. It takes place in a multi-level setting, for communities within communities within communities. It sometimes stalls, goes backwards, occasionally collapses; often however the social processes involved pass thresholds and cascading change occurs. It is at times like these where multi-level interactions can be positive or negative, where power – social, economic and political – is firmly in play, that governments can go wrong.

The underlying problem is that it is times like these that call for a radical shift from the self-interested individual to the small cooperative group. It is in these settings where meaningful initiative and power often resides, where action is possible, where evolutionary fitness is established, and where the emergence of fresh social, economic and political structures can take place.

It is through the instinctive leadership, state action or self-organized formation of small cooperative groups that humans in a community achieve common benefit through communication and sharing, enabling learning, innovation, and growth. It is the same instinct that enables multi-level cultural evolution in human communities, generating ever more complex systems and structures. This is the causal dynamics underlying the growth of community provisioning systems.

The systems and structures that evolve in this way, prescriptive state systems, collaborative cooperative systems, market systems and informal systems are sometimes successful and sometimes failures, lacking key design elements. Ostrom has identified a number of core design principles that characterize successful group functioning. These provide a useful checklist to anyone interested in studying, forming or improving on group functioning and dynamics.

These principles are not always easy or obvious to implement especially in crisis situations where strong political and social governance is seen as essential, or external governance is imposed without consent on the communities.

Top-down controls and governance meet with bottom-up self-organized small group structures, interacting multi-level webs of stakeholders emerge with often widely differing needs and wants, resources and cultures, power and networks.

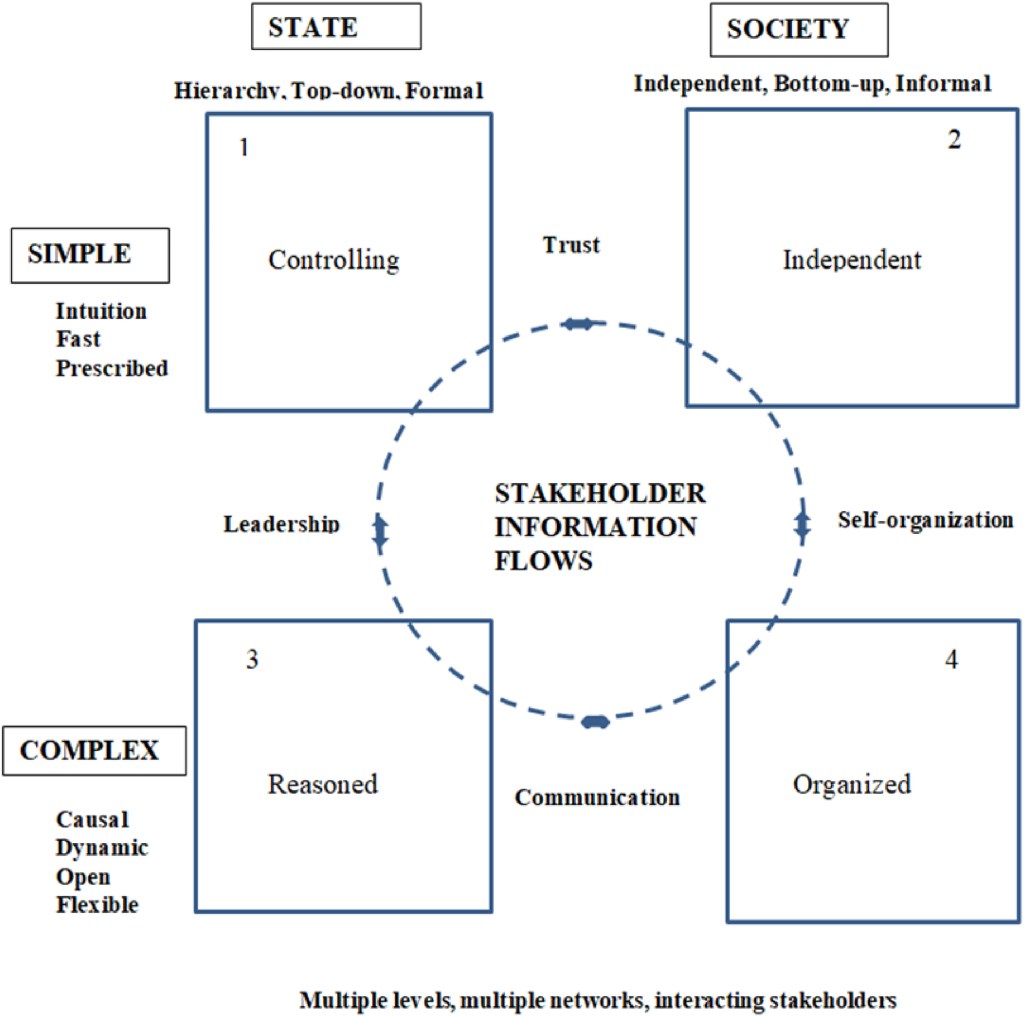

Any resolution of these interacting tangled webs will rest on an understanding of the complex social mechanisms that are at work. These are identified in following figure. This figure is useful because it considers not only the structure of the systems, but how information is moving within the system. This could illuminate the need for improved flows providing a basis for recommendations.

The information flows that are the culmination of this figure are central to the negotiations within and between stakeholder alliances and groupings, often in a multi-level setting, and are the product of interacting complex social mechanisms – delivery systems, stakeholder action fields, technology evolution systems and value exchange fields.

Finding an even temporary balance between state and independence and between the attractions of simple choice, unidimensional or single focus driven decision making which greatly limits openness to the ideas and concerns of others, and the acceptance of complexity, bureaucratic autonomy for collective choices is far from easy, especially when seeking to meet, in part at least, the demands of the four intersecting complex social mechanisms depicted in adjacent figure in an assemblage of provisioning systems with differing cultures and values.

Following table summarises the research issues in the community-provisioning system framework.

| Community life dynamics | Provisioning systems dynamics | Getting things right |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals Values Capabilities Diversity Specialization Perceptions Creativity Logics Collectives Friendship Communication Trust Cooperation, competition Networks, alliances, coalitions Self-organization – spontaneous, lasting Emergence – multilevel, entities Innovation Stability, growth/collapse Equality Resilience, sustainability | Community specific Needs, wants – goods, services, experiences, ideas Location, geography, history Infrastructures Networks Local cultures Adaptive cycle positioning Satisfaction, QOL, growth Sustainability, resilience Emerging diversity Assemblage networks State prescriptive Cooperative. Collaborative Platforms, sharing Market value exchange systems Formal, informal Unregulated, illegal Adjacencies – supervening, co-existing, embedded Inter-system linkages, coalitions Flows of communication, power, trust, information Culture conflicts, clashes, merges Corruption | Diagnose, Design, Map Stakeholders – individuals, small groups, Entities, institutions Linkages, adjacencies, competing, cooperative, coexisting, supervening Dynamics – stable, unstable; chaotic Outcomes – Satisfaction, QOL, growth, de-growth; fairness, justice, inclusion Choice processes – stakeholders; state, self-organized; top-down, bottom-up; simple, complex Complex social mechanisms Delivery systems Stakeholder action fields Innovation systems Value exchange fields Path dependence Specific tensions within, between Structure/ diversity Top-down, bottom-up decisions Macro-micro-macro interface Adaptive cycle positioning |

Community provisioning systems are particularly important to meet the needs of daily life and bridge gaps that exist when systems with differing cultures interact with each other – medical and managerial being an example. Social change and many other factors require both immediate and long-term responses to complex evolving problems that engage with multi-level complex systems.

There is a need to rethink contemporary optimization, rework the logics we apply, effect complexity insights, not only at a meso level but also at searching for an understanding the evolutionary dynamics that are driving change at all levels. Ultimately it is the individuals, small groups, entities, organisations and institutions all making choices in response to their individual and group perceptions that drive the evolution of a community provisioning system. Creating positive social impact and societal evolution is easier said than done.

Nevertheless, that is the very work, the change, the radical, urgent transformation demanded of macromarketing and indeed marketing, by climate change, a pandemic and the numerous local-to-global crises communities are confronted with in their everyday lives around the world.

Macromarketers should be at the centre of this transformation but this will take a rethinking of what marketing, marketing systems and provisioning systems are about.