Industrial strategy is experiencing a renaissance.

Getting the details right matter.

Mission-oriented industrial strategy needs to be more than words if we want to avoid missions becoming part of the problem, not the solution.

This report (Mission-oriented industrial strategy: global insights) is based on research conducted over the past several years, led by Professor Mazzucato and her team at IIPP.

It offers practical insights gained from work with governments around the world – on opportunities ranging from healthy and sustainable housing estates in our local Camden Council to the ecological transition in Brazil – that are advancing new approaches to bring economic, social, and environmental policy goals into alignment at the centre of their growth strategies.

The report offers a one-stop-shop for how to design, implement, and govern mission-oriented industrial strategies and examines the tools, institutions, partnerships, and capabilities governments need to deliver transformative change.

Countries must decide what missions can help direct their economies.

The challenges leading to these missions are similar globally: global warming, weak health systems, insufficient access to decent housing, and the need to govern our digital platforms in the public interest.

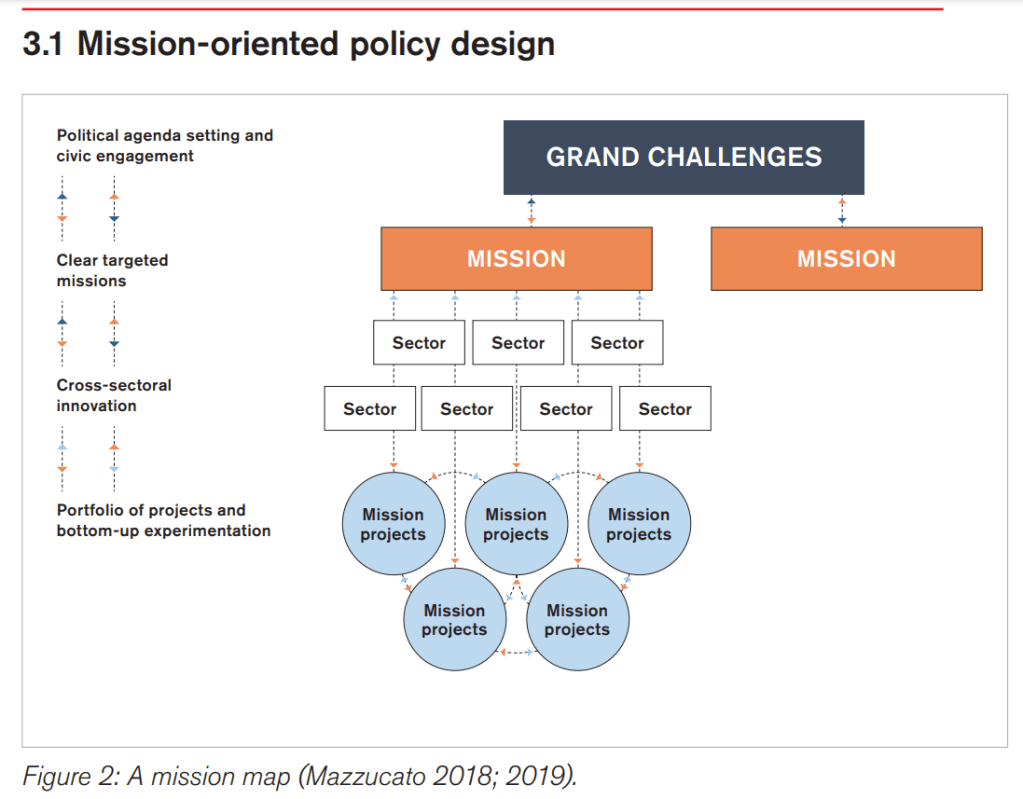

How they play out will depend on local contexts and the ways that different stakeholders come together. A mission oriented approach will ensure that industrial strategy creates opportunities not only for companies, but also for cross-sectoral innovation, investment and public–private collaboration that contribute to solving problems that matter to people and the planet.

This is not about moderating growth; on the contrary, because missions require investment and innovation, they generate solutions (technological and organisational changes) with dynamic spillovers, like those that allowed us to reach the moon (camera phones, software, baby formula, etc.). Missions can lead to a new direction for growth that changes how value is created and distributed across the economy ex ante, enabling a predistributive approach.

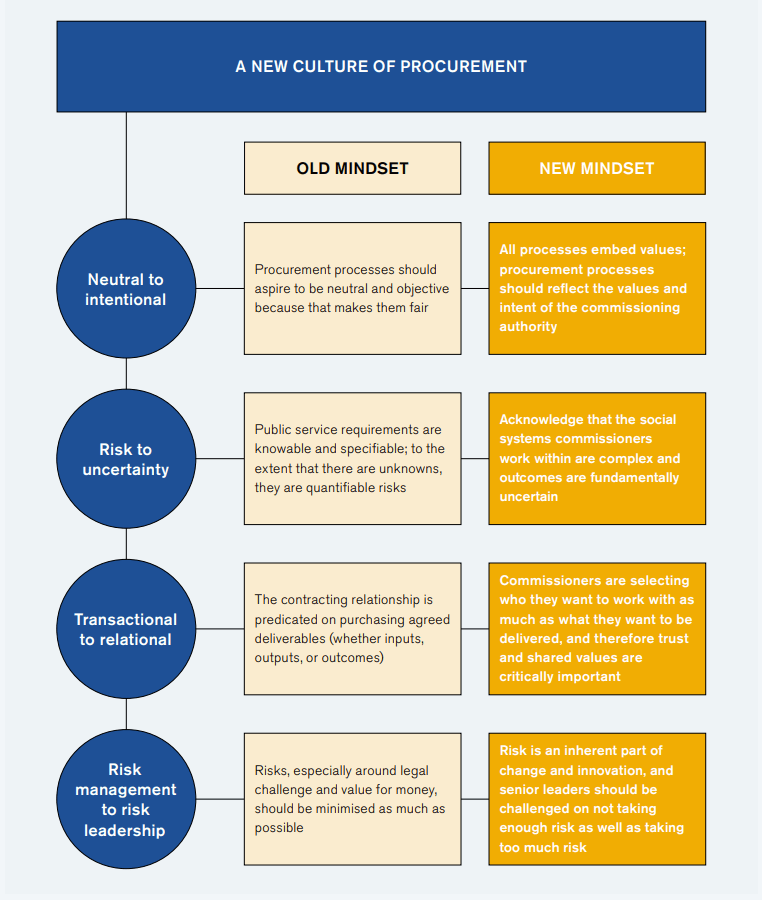

Mission orientation that goes beyond window dressing requires fundamental changes in how governments work, to ensure that key institutions and tools are fit for purpose, that partnerships between economic actors are mutualistic, that new voices are brought into decisions about how the economy functions, and that the state has the necessary capabilities and confidence. The successful implementation of mission-oriented industrial strategy requires letting go of old assumptions about the role of the state in the economy, and instead recognising and investing in its transformational capacity.

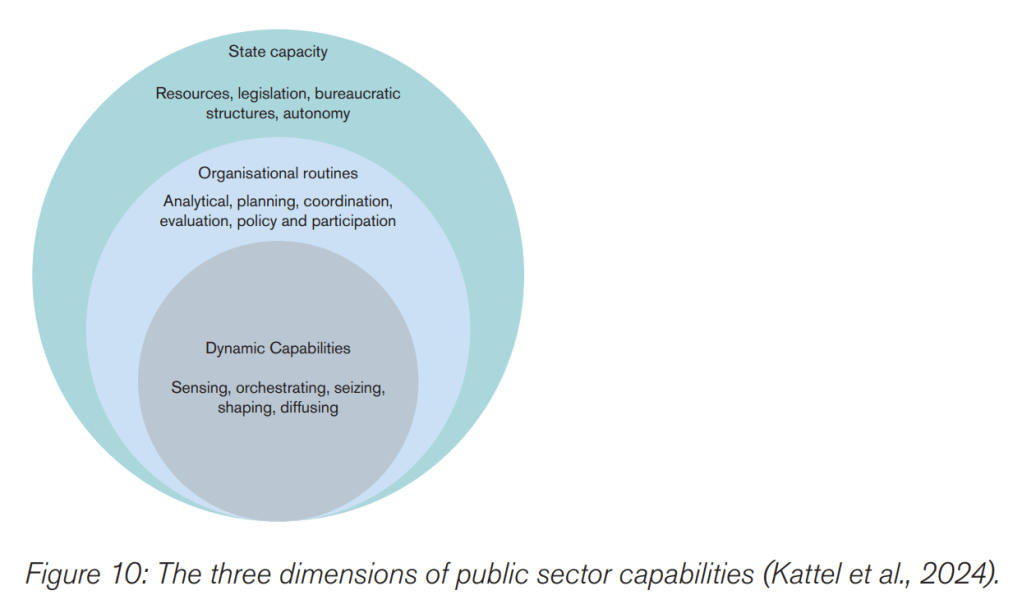

There is no established consensus on the number and content of public sector dynamic capabilities. We propose to typologise these capabilities as follows (cf. Spanó et al. 2024):

1. Sense-making (system awareness): i.e., the ability to scan and make sense of the environment where a public organisation operates to analyse opportunities and threats. This can be broken into ‘low order’ routines:

i) strategic thinking to discern potential challenges;

ii) analytical thinking to discern potential opportunities;

iii) analytical thinking to discern political leverage and bargaining

2. Connecting (policy coordination): i.e., the ability to coordinate the connections, interfaces and linkages between the functions performed by a public organisation in its relation with the external environment. This can be broken into ‘low order’ routines:

i) vertical coordination among leadership and frontline of the public organisation;

ii) horizontal coordination among silos/departments in the public organisations; and

iii) inter-organizational coordination between the public organisation and other relevant ones.

3. Seizing (action as experimentation): i.e., the ability to take advantage of emerging opportunities within a public organisation’s external environment. This can be broken into ‘low order’ routines:

i) strategic investment and allocation of non-monetary resources;

ii) decision-making procedures that avoid bias and welcome innovation; and

iii) stakeholder management.

4. Shaping (transforming contexts): i.e., the ability to change a public organisation’s internal resources in view of changes in the external environment. This can be broken down into ‘low order’ routines:

i) management and prioritisation of stable financial funds;

ii) insourcing and outsourcing of goods, Human Resources, projects, and processes;

iii) management, reskilling and reshaping of HRs.

5. Learning (organisational learning): i.e., the ability to control and manage how the routines developed by a public organisation are monitored, assessed, and ultimately discarded or institutionalised. This can be broken into ‘low-order’ routines:

i) politico-administrative learning;

ii) politico-economic learning; and

iii) techno-economic learning.

Dynamic capabilities identify the set of specific abilities that enable the renewal of governments — more specifically, through the structuring and restructuring of their organisational routines and broader state capacity:

- In terms of capabilities, they support the development of routines that bolster governments’ ability to make the most of its available resources and achieve their desired goals.

- In terms of capacity, they support the identification, acquisition, or reallocation of the resources that bolster overnments’ ability to achieve their desired goals.