Wisdom is the hallmark of social judgment, but how people across cultures recognize wisdom remains unclear—distinct philosophical traditions suggest different views of wisdom’s cardinal features.

This article in Nature Communications explores perception of wise minds across 16 socio-economically and culturally diverse convenience samples from 12 countries.

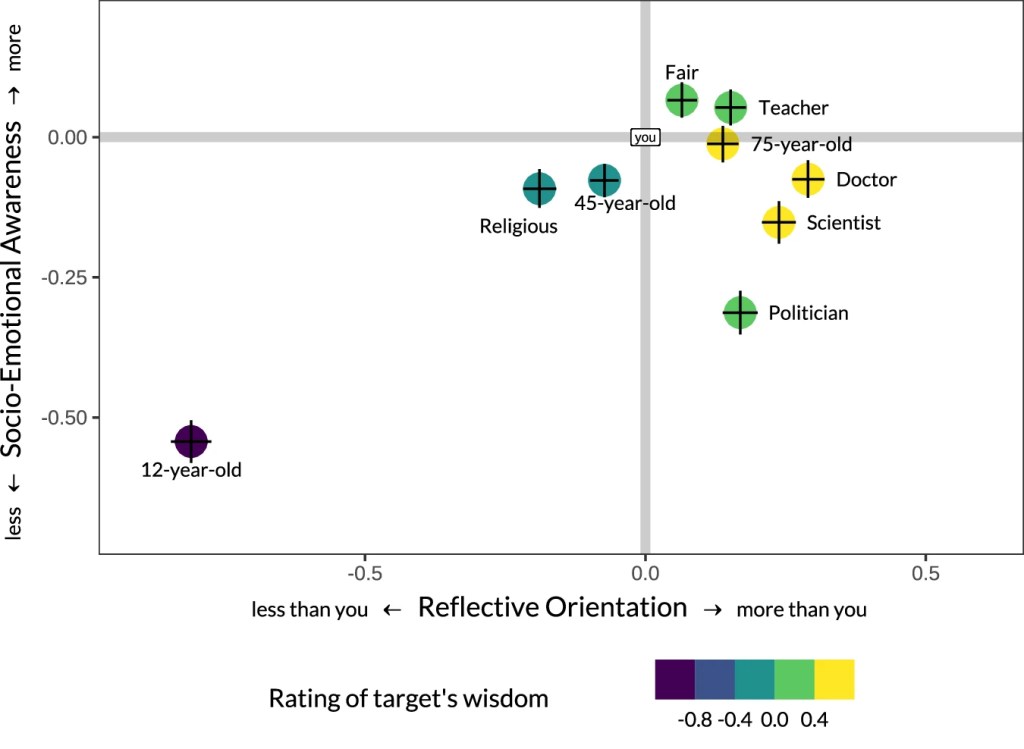

Targets were regressed on the two latent dimensions and explicit ratings of wisdom. Values of ‘you’ were used as a reference category in regression analyses and were therefore set to zero. Thus, all other scores represent the distances from ‘you.’ The bars represent 95% confidence intervals of estimated parameters for each axis.

Participants assessed wisdom exemplars, non-exemplars, and themselves on 19 socio-cognitive characteristics, subsequently rating targets’ wisdom, knowledge, and understanding. Analyses reveal two positively related dimensions—Reflective Orientation and Socio-Emotional Awareness.

These dimensions are consistent across the studied cultural regions and interact when informing wisdom ratings: wisest targets—as perceived by participants—score high on both dimensions, whereas the least wise are not reflective but moderately socio-emotional.

Additionally, individuals view themselves as less reflective butmore socio-emotionally aware than most wisdom exemplars. These findings expand folk psychology and social judgment research beyond the Global North, showing how individuals perceive desirable cognitive and socio-emotional qualities, and contribute to an understanding of mind perception.

A Network graph representation of items demonstrating closer (and stronger) associations of items making up each factor.

B Unstandardized factor loadings of items of the two factors taken from a multigroup multilevel confirmatory factor analysis.

Three further observations are noteworthy.

First, after holding the Reflective Orientation constant, Socio-Emotional Awareness showed a negative association with wisdom ratings. Thus, among equally (less) reflective individuals, targets that were perceived as more caring were viewed as less wise. To elaborate, consider an example of evaluating people who give indiscriminately or people who are mindlessly driven by emotions. These individuals might be admired and revered in some instances, but unlikely to be perceived as wise. Reflective Orientation

thus seems to be a necessary condition for obtaining higher wisdom, whereas Socio-Emotional Awareness positively contributes to wisdom only when the first condition is satisfied.

Second, while the cross-cultural agreement about the targets’ positions with respect to Reflective Orientation was high, we found notable cultural variation in their positions with respect to Socio-Emotional Awareness. Several conjectures may post-hoc explain this observation. One interpretation could involve the grounding of social and emotional acts in local norms, which are more subject to culturally-mediated scripts compared to a more generally applied logic or self-control, at least in the societies examined in the present study.

For instance, the attribution of ‘care for others’ feelings,’ one of our 19 wisdom-related characteristics, to doctors might vary more across cultures than the attribution of ‘logical thinking.’

Another interpretation is that Reflective Orientation may be considered the primary element of wisdom perception across cultures, whereas Socio-Emotional Awareness comes in as a secondary, contextually and culturally dependent element.

This conjecture aligns with cultural narratives that often depict wise individuals, such as hermits or philosophers, who, despite their social detachment, are revered for their profound insights into virtuous living. Therefore, while Socio-Emotional Awareness is an integral aspect of wisdom, its attribution to specific targets, such as professionals or leaders, exhibits greater variability across cultures. This is likely due to its encompassing of a broader range of characteristics, which include both solitary introspection and socially engaged behaviors, leading to diverse cultural interpretations in the attribution of these traits in the context of wisdom.

Third, the two latent dimensions appeared to be differentially susceptible to self-enhancement bias: in most societies, people considered themselves superior to exemplars on socio-emotional competencies while inferior on reflective competencies. The latter observation expands on prior research on personality (i.e., greater selfenhancement of agreeableness versus conscientiousness) and the role of cultural factors such as religiosity for self-enhancement on warmth rather than competence. Contrary to the existing evidence, this self-enhancement tendency was present in East Asia as well as in other parts of the world.

Finally, our results might explain why philosophers have long debated whether there are two kinds of wisdom—practical and theoretical wisdom—or whether these two forms of wisdom are in some way unified. The two types of wisdom examined by philosophers may be rooted in the two dimensions of wisdom perception such that theoretical wisdom(or sophia) is more influenced by the perception of characteristics aligned with Reflective Orientation, whereas practical wisdom (or phronesis) is more influenced by the perception of socioemotional characteristics.

Alternatively, Reflective Orientation may be informing both practical and theoretical wisdom, whereas Socio-Emotional Awareness chiefly contributes to the practical wisdom; a fruitful avenue for future research.

One response to “wisdom perception across 12 countries”

[…] Wisdom perception across 12 countries […]

LikeLike