“A Pragmatist Approach to Complexity Theorizing in Project Studies: Orders and Levels” offers pragmatist recommendations to develop strong theorizing strategies organized in a triad:

1. orders of theorizing (degree of recursiveness of the theorizing process),

2. levels of theorizing (interactions between micro, meso, and macro loci of analysis), and

3. the integration between orders and levels brought together in a recursive relationship of co-construction.

The article offers four main contributions to complexity theorizing in project studies:

– pragmatism is useful,

– deeper attention should be paid to theorizing across levels,

– third-order theorizing is needed, and

– complexifying terminology is required.

“Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.”

Shakespeare – Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2.

Most scholars “acknowledge the complexity of the world but deny it in [their] theorizing” . Such lack of theoretical sophistication is generated by dualistic theorizing, which more often than not seeks to provide “a clear-cut and decisive contrast, a well-defined boundary, and no overlap between categories” of complexity theories. However, complexity is “a joint property of the system and its interaction with another system, most often an observer and/or controller” (Casti -Complexification: Explaining a paradoxical world through the science of surprise (1994),p. 269). Thus, we contend, any theorizing strategy that ignores the interactions between the (hard) system and the (soft) observer is bound to generate inadequate theories.

“How can a pragmatist approach enable improved theorizing strategies for complexity theory in project studies?”

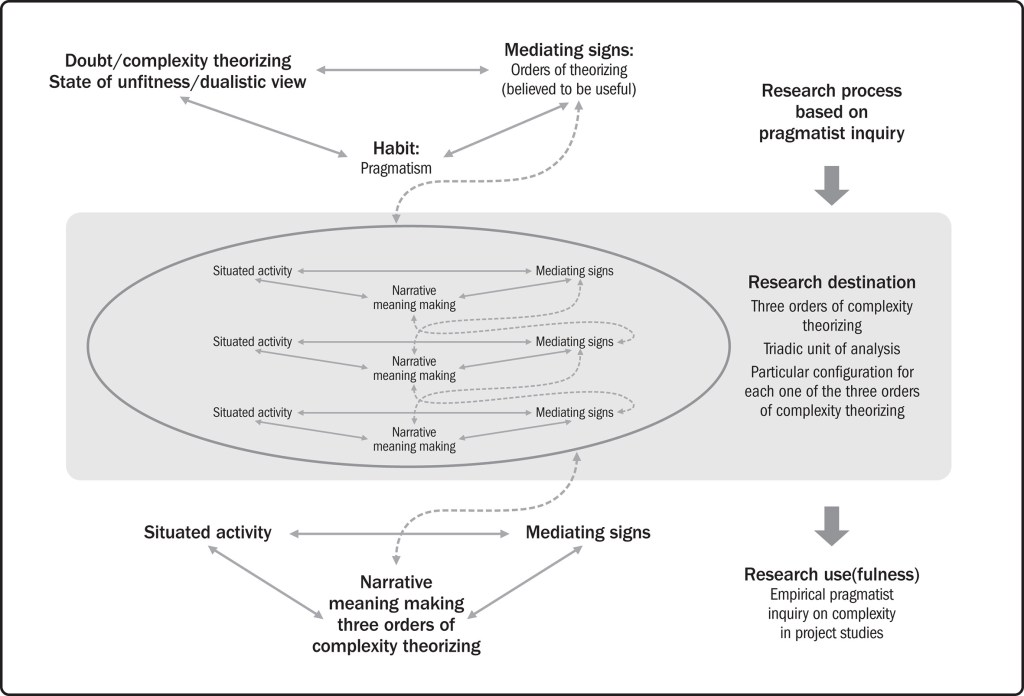

Complexity theorizing in project studies is mediated by and mediating orders of theorizing.

Indeed, narrative meaning-making allows reflexivity about—and intelligence of—the empirical situation under inquiry (situated activity) and deliberation leading to inquiry outcomes (mediating signs).

Table 1 briefly describes the three orders of theorizing for complexity in project studies, highlight some key characteristics of their triadic categories.

Table 1 Three Orders of Theorizing: A Summary of Key Characteristics

| First-Order Theorizing | Second-Order Theorizing | Third-Order Theorizing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Situated activity | Ontology > epistemology Simplifying and reductionist ontology Positivism | Epistemology > ontology Open-world ontology Performative epistemology Constructivism | Ontology <>epistemology Recursive nondualistic relationship between ontology and epistemology Radical constructivism |

| Narrative meaning-making | Disjunctive thinking Logico-scientific mode Learning I (Following the rules: Are we doing things right?) | Conjunctive thinking Narrative mode Learning II (Changing the rules: Are we doing the right things?) | Ingenium, prescience Poetic mode Learning III (Reflecting on how we think about rules: How do we decide what is right?) |

| Mediating signs | Trivial machine First-order cybernetics Teleology (pertains to systems whose purposes are determined by an observer) Observed systems | Non-trivial machine Second-order cybernetics Teleonomy (pertains to systems whose purposes are determined by feedback with their environment) Observing systems | Non-trivial machine Third-order cybernetics Teleology and teleonomy Mutually observing systems |

The literature on complex systems has long drawn attention to their recursive nature.

Complex systems are fractal: like Russian dolls, they exhibit the same shape at different levels of granularity and what happens at one level will influence the levels above and below through feedback loops.

Yet, it is not common to distinguish between levels of theorizing in complexity research in project settings. To date, many project scholars have focused on describing projects as complex adaptive systems, encouraging a departure from traditional and reductionist conceptions of projects and project management to address challenges arising from complexity or characterizing complexity and identifying its contributing factors. How are we to develop a comprehensive theory of complexity in project settings if we ignore the feedback loops between the factors contributing to complexity and the challenges and outcomes that arise from the interactions between factors?

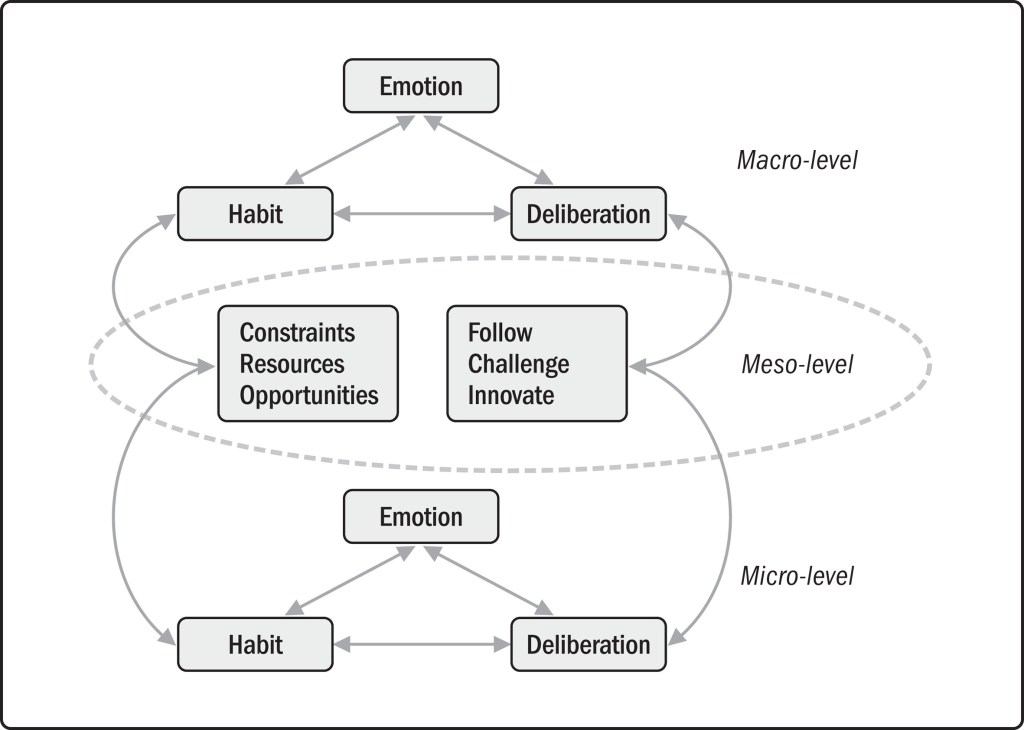

Pragmatism straddles the micro–macro divide that separates theories emphasizing, for example, either the primacy of structure or that of rational agency. This kind of dualism opposes theorizing that aggregates micro-level phenomena (individual actions) to produce macro-level outcomes (structures), and theorizing that pulls down macro-level events to the level of individuals.

Theorizing the linkages between micro and macro levels using a simple model only enables us to conceive of linear relationships between levels.

Using this linear strategy, microfoundation theories do not deal well with one central aspect of complexity theory, emergence: “In all, the notion of ‘emergence’ remains vague and thus opportunities remain for both micro and macro disciplines to carefully specify the underlying actors, social mechanisms, forms of aggregation and interaction that lead to emergent outcomes”. This observation suggests that something is missing from traditional approaches to theorizing complexity between the micro and macro levels: “This distinction (or implicit dualism) hinders multi-level theorizing and creates a barrier to understanding organizational change because it misses how phenomena co-constitute each other“. This suggests that something is missing from traditional approaches to theorizing complexity between the micro and macro levels.

Strategic behavior generated by the habit-emotion-deliberation triad can be observed at multiple levels, and that processes of enactment are structurally similar at the individual and organizational levels. Their account indicates that macro-level structures provide constraints but also opportunities and resources, whereas individuals at the micro-level have the ability to follow, challenge, and innovate the macro-level social conventions.

Together these provide a more nuanced account of the meso-level relationships between micro and macro levels.

The theorizing process that defines our three orders is constructed through the pragmatist triad: situated activity, narrative meaning-making, and mediating signs.

The aim of the theorizing process is to produce models (mediating signs) in a manner that action and thought are aligned. The three levels of theorizing are built on another pragmatist triad (habit, emotion, deliberation) at the micro and macro levels, linked by the factors (resources, constraints, opportunities) and mechanisms (follow, challenge, innovate) at the meso level, enabling to connect agency and structure.

Thus, the two main theory-building categorizing processes are distinct from each other: orders are concerned with the degree of recursiveness of theorizing, whereas levels are concerned with the level of agregation of the theorizing objects (macro or micro) and how they are related (meso).

Orders and levels link up as follows: Mediating signs as theoretical models provide social actors with models of action (habits), which can then be mobilized across and/or between levels.

This integration of orders and levels of theorizing is crucial to further complexify complexity theorizing.

In first-order theorizing, the articulation between orders and levels operates as a single loop: Does the mediating sign as a model provide a good template to capture the interactions between levels?

The approach assumes a unitary context where stakeholders agree on what needs to be done.

In second-order theorizing, the articulation between orders and levels operates as a double loop: Not only does one check that the model is appropriately capturing what is going on (are we doing things right?); one also enquires if the model is appropriately contructed (are we doing the right thing?). In other words, second-order theorizing invites a critical evaluation of the theory (mediating signs and habits) from within.

In third-order theorizing, a third feedback loop is added, challenging the purposes that inform the inquiry (why are we doing this?). Here, the feedback loop is no longer between a theory and a contextualized object but between theories that contextualize objects in different ways. If a project is defined as “any action subject to prior examination by a validation or funding authority”, then the authority may be an individual, organization, or government.

This insight offers a pragmatist orders and levels approach to theorizing strategies for complexity theory, describes four major contributions.

1. First, adopting a pragmatist stance, this article takes issue with the prevailing dualistic deadlock in complexity theorizing, including the either-or categorization of existing complexity theories in project studies. Consequently, it offers a pragmatist approach to theorizing strategies for complexity theory along two interrelated categorizing processes: orders and levels brought together in a recursive relationship. This article thus shows how, in a quest for theoretical complexification, a research may display multiorder and multilevel theorizing.

2. Second, beyond the established distinction between first-order theorizing characterized by a disjunctive thinking and second-order theorizing characterized by a conjunctive thinking, we propose a novel third-order theorizing characterized by a more complex and poetic thinking that is akin to prescience, which we contend, offers plentiful opportunities for enriching the variety of our understandings of complexity and complexity theorizing in project studies.

3. Third, through the three-level model of complexity theorizing, we contribute to literature by directing greater attention to the under-researched and under-theorized meso level, where the interactions and transformations between micro-level factors and elements and macro-level outcomes occur.

4. Fourth and last, our construction of orders and levels of theorizing strategies for complexity theory in project studies provides an illustration of how pragmatist principles can be operationalized to develop a useful theorizing process (narrative meaning-making) for a particular topic (situated activity) through the selection of appropriate lenses (orders and levels).