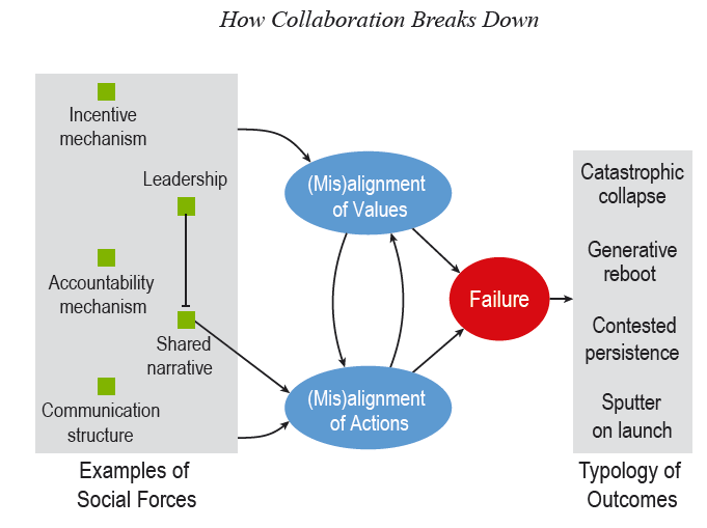

Simon DeDeo and many other authors describe in this chapter how humans may be “super-cooperators,” but no collaboration lasts forever. This chapter summarizes the outcome of an interdisciplinary collaboration between political, social, economic, and cognitive scientists into the question of collaboration collapse. It locates the breakdown of collaboration downstream from the failure to align on either values or actions. A fourfold taxonomy is presented of the consequence of these failures: catastrophic collapse, generative reboot, contested persistence, and sputter on launch.

Each failure mode is illustrated by case studies (e.g., the breakup of the Beatles, the collapse of the Hawai‘ian kapu system, the failure of the Kyoto Protocol, kinship taxation, resistance to antibiotics) to demonstrate how general principles of our taxonomy unfold over a range of historical, political, and economic contexts. Understanding the mechanisms that underpin successful collaborations and the taxonomies of dysfunction might inform efforts in pursuit of stable collaboration and enable interventions that do not disrupt or enfeeble alignment mechanisms.

The complexity of human cognition and culture means that an enormous variety of causes interact to both sustain and interfere with collaboration (the alignment of values) and coordination (the alignment of actions).

Misalignment of values and actions may arise separately.

The emergence of misalignment in one leads to feedback effects on the other, either directly (e.g., failure to coordinate may lead to the divergence of values among the collaborators) or via social forces (misalignment of values may cause a legitimacy crisis that makes it impossible for a leader to correctly coordinate action).

A taxonomy of breakdown by failure type, with samples of each and the

type of mismatch created:

| Failure Type | Example | Mismatch Type |

| Catastrophic collapse | Breakup of the Beatles | Values |

| Catastrophic collapse | Collapse of the Hawai‘ian kapu | Actions |

| Generative reboot | Copenhagen Climate Conference | Values |

| Generative reboot | Scaling Wikipedia | Actions |

| Contested persistence | Kinship tax | Values |

| Contested persistence | Fencing among the Maasai | Actions |

| Sputter on launch | Antibiotic resistance | Actions |

How Collaboration Breaks Down

Four key epistemic tasks appear to be in play when we seek to initiate and maintain a collaboration:

- We have to imagine a future we want and to share that imagination with other agents.

(We have to be able to set goals and to share those representations with others.) - We have to foresee how collaboration can make real that desired future and again share that perception.

(We have to understand the structure of potential collaboration and its benefits.) - We have to predict the behaviors of others regarding their willingness and abilities to collaborate, how they might collaborate, and whether they can be trusted.

(We have to understand the values and capacities of others.) - We have to manage the risks associated with uncertainty due to the temporal and spatial extent of a collaboration. When rewards to oneself depend on the actions of others, for example, collaboration may require that participants contribute without specific knowledge of reward but instead with a general expectation of reciprocity. When rewards to others are uncertain, we have to rely on proxies and signals (e.g., market prices) to see how we might contribute.

(We have to see any particular aspect of a collaboration as part of a larger context of information- and reward-sharing.)

Collaborations are composed of individuals, whose psychologies and capacities define and limit how their values and actions can be aligned.

Individuals may be members of multiple collaborations at the same time, leading to both synergies and challenges: one might be simultaneously a member of a tribe, a business endeavor, and a political party.

This can lead to competing demands and new potentials for misalignment between value systems. Collaborations themselves exist in a common wider context, interfering or coordinating with each other both through ties of common membership

If we can identify the generic features of how collaborations break down, we can better identify which collaborations might be in danger, plan when failure is near, and use this information to build more robust collaborations in the future. To that end, we offer a simple message: collaboration failure is best understood through the causal drivers responsible for misalignment—either of values or actions—and that the causal sequelae of these misalignments trace out a small number of basic patterns.

One consequence of our analysis is the idea that policy makers conduct what we call an “ alignment review”: an assessment of how a policy change will affect the alignment of values and actions of the various collaborations that exist within the society in question. Such a review would be a natural

extension of already existing practices. It is increasingly common to consider the effect policy changes might have on the culture as it currently exists, and policy makers are increasingly aware of the phenomenon of institutional crowding-out —the perverse effects that novel external incentives can have on behavior previously guided by longer-standing traditions.

Our work suggests a larger framework for conducting this kind of analysis.

By becoming familiar with the values and coordination mechanisms that underlie a society’s successful collaborations—as well as the taxonomies of dysfunction described in this chapter—policy makers have a chance to investigate how necessary alignments might be stabilized. This will also enable them to make sure that policy interventions do not disrupt or enfeeble these alignment mechanisms, or, if required, that truly necessary interventions provide new mechanisms to replace old ones.