Become a Better Problem Solver by Telling Better Stories is a great article from Arnaud Chevallier, Albrecht Enders, and Jean-Louis Barsoux on MIT SMR.

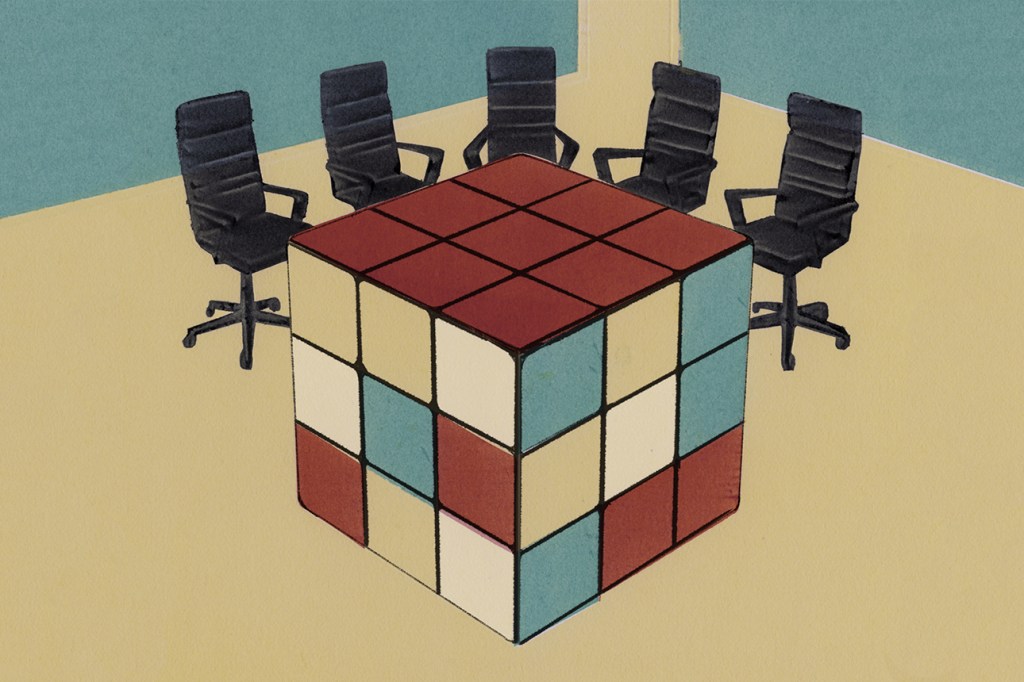

One of the biggest obstacles to effective decision-making is failure to define the problem well.

Invoking the power of narrative and a simple story structure can help ensure that teams are solving the right problem.

To find better answers, it is necessary to ask better questions. This is called problem framing. Often neglected, this initial step in the decision-making sequence sets the trajectory for generating alternative options. It is critical for two reasons: It can reveal new possible solutions, and it avoids wasting time, money, and effort on half-baked ideas.

As with any high-order activity,

it takes mastery to make it look simple.

An effectively framed problem is simple to understand, which may explain why executives often underestimate the effort that good problem formulation requires. As with any high-order activity, it takes mastery to make it look simple. Executives don’t realize how tricky framing can be until they try it. To compound the challenge, plenty has been written on the importance of framing, but there’s been little concrete guidance on how to do it. Senior executives are especially prone to overestimating the value of experience as a guide to solving novel challenges.

Framing Fails

1. Assuming everyone sees the same problem. The biggest pitfall comes when executives take for granted that all stakeholders have the same intuitive understanding of the problem. This is hardly ever the case.

By default, we frame problems without a great deal of thought, using routines, heuristics, and experience to bypass formal analysis. We instinctively recognize the type of problem before us and reach for familiar solutions. his makes sense for problems that are urgent, recurring, and low risk, where experience is most likely to lead to a good answer. The trouble starts when we try to apply the same approach to problems that are complex, novel, or high risk.

When relying on intuition, cognitive biases (such as overconfidence and confirmation bias) can muddle the decision-making process. The deep smarts that enable people to discern problems and propose instant remedies in their domains of expertise quickly become a liability outside it. The French call this déformation professionnelle — the tendency to see any problem through the distorting lens of one’s professional experience.

2. Targeting the wrong problem. Even when someone makes a conscious effort to articulate the problem and not rely on instinct, they might frame it too narrowly or too broadly.

An effective frame captures the essence of the problem. If it’s too narrow, it risks being ineffective by focusing on just one of the drivers, such as demand for parking spaces, and missing important or emerging issues altogether. If it’s too broad, it risks stretching attention and resources across too many concerns, including ones that have little or no relevance.

3. Pushing a single perspective. Another common trap is unilateral framing. Having defined the challenge alone or with like-minded colleagues, problem solvers are often blindsided by objections from critical stakeholders — especially those whose support they had taken for granted.

A cognitive bias known as the false consensus effect leads us to overestimate the extent to which others will perceive a situation in the same way we do. As a result, we underinvest in engaging others or testing our frames.

Having defined the challenge alone or with like-minded colleagues, problem solvers are often blindsided by objections from critical stakeholders.

There are other traps in strategic decision-making, such as failure to consider innovative solutions or simply choosing a bad one. Our point is that effective framing is more important and more difficult than it seems.

A process is necessary.

We propose a two-part solution: Frame and reframe.

Creating an Initial Frame

Research and our experience with executives show that using a basic story framework can help people make sense of complex information. Storytelling is not only useful for persuading others but also valuable for thinking through ambiguous information.

Storytelling is not only useful for persuading others but also valuable for thinking through ambiguous information.

Storytelling makes it possible to structure this complexity by summarizing the problem in the form of a single overarching question — a quest — that will lead to the solution. An effective quest has just three elements:

- A hero — the main protagonist. Depending on the challenge, it could be a single person, a team, an ad hoc project group, a unit, or even the whole organization.

- A treasure — the hero’s aspiration. This captures the one overriding goal, be it transforming the company, expanding into new markets, upgrading a team, or changing careers.

- A dragon — the chief obstacle. This is the complication preventing the hero from getting the treasure. A compelling dragon creates a strong hook and a shared understanding of the challenge to be faced.

Pulled together, these three elements define the quest, which takes the form, How may [the hero] get [the treasure], given [the dragon]? A quest works best with one hero, one treasure, and one dragon — otherwise, it’s more than one story.

When someone is dealing with multiple dragons, it’s better to ask whether there is a single challenge or whether it might be more sensible to place the different dragons into separate problem frames. (See “The Do’s and Don’ts of Framing.”)

The story framework highlights the critical pain points and lays bare assumptions

Framing a Better Quest

One trap to avoid when using this method is the temptation to stick with the first quest that comes to mind. Developing a sound quest is an iterative process, and going deeper into understanding a problem requires stress-testing the quest.

Picking the wrong hero can result in efforts that fail to gain traction.

Focusing on the wrong treasure can mean that efforts won’t yield the desired results.

Picking the wrong dragon means wasting energy on pointless battles.

Why stories Help

Statistician George Box famously said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” The key to developing a useful model is to include all that matters, but only what matters. This is how the story approach helps with problem-solving: by providing a straightforward way to define and clarify the problem to be solved. A concise description of the quest can lead to a clear strategy for moving forward.

The brevity of the quest narrative is part of its strength.

The story ingredients depersonalize criticism.

Stories tap into our playfulness.

The key to developing a useful model is to include all that matters, but only what matters.

Beyond being an analytical challenge, complex problem-solving is also a people challenge. It requires input, different perspectives, involvement, and buy-in from other stakeholders.

The Do’s and Don’ts of Framing

The quest is a classic storytelling technique to help structure a problem. Executives typically make several mistakes as they construct their own quests. Here are five things to keep in mind.

- Remember the dragon. The hero and treasure establish the protagonist and the goal. But one key ingredient is missing: tension. To identify the chief barrier to a goal, introduce the dragon with “However …” or “But … .”

- Don’t use “and.” Each part should have one element, and only one. If there are more, they should either be reconciled under an umbrella term or divided into separate challenges. If there are several potential dragons, choose the one that creates the most relevant tension.

- Exclude unnecessary details. A snappy frame is more useful than a detailed one. Include only what is needed to tell a coherent story, excluding everything else.

- Be consistent. Use the same terms when moving from the individual elements to the overall quest. Synonyms and ambiguous phrasing only cause confusion. The quest should be self-contained and easily understandable, even by a novice.

- Don’t aim for perfection. The first attempt at framing is just a communication tool. There is no such thing as the “right” frame — just a better one. Chances are that sharing the frame with others will reveal new angles and false assumptions that help improve it.