Learning by thinking in natural and artificial minds:

Canonical cases of learning involve novel observations external to the mind, but learning can also occur through mental processes such as explaining to oneself, mental simulation, analogical comparison, and reasoning.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) reveal that such learning is not restricted to human minds: artificial minds can also self-correct and arrive at new conclusions by engaging in processes of ‘learning by thinking’ (LbT).

How can elements already in the mind generate new knowledge?

This article aims to resolve this paradox, and in so doing highlights an important feature of natural and artificial minds – to navigate uncertain environments with variable goals, minds with limited resources must construct knowledge representations ‘on demand’. LbT supports this construction.

Learning is central to cognitive science. A great deal of research has accordingly focused on ‘learning from observation’ – cases in which the learner obtains new information from their senses (e.g., a visual observation or a speaker’s testimony) and updates their mental representations accordingly. What this focus excludes is less canonical instances of learning that occur within the mind – a phenomenon called ‘learning by thinking’ (LbT).

Consider the scientist who achieves new insight through a thought experiment, the driver who discovers how to navigate an obstacle through mental simulation, or the writer who learns something new by trying to explain her ideas. In each case, learning occurs in the absence of novel input from the external world.

Recent evidence from psychology demonstrates the ubiquity of LbT: both children and adults learn through explanation, simulation, comparison, and more. However, the latest advances in computer science bring the phenomenon of LbT into starkest relief.

Consider the following

dialogue with GPT-4, a large language model (LLM):

1. USER:

Is 420 60% of 700?

2. GPT-4:

No, 420 is not 60% of 700.

To find 60% of 700:

0.60 × 700 = 420

Actually, I made a mistake in my initial response.

420 is indeed 60% of 700.

LbT is a paradoxical phenomenon.

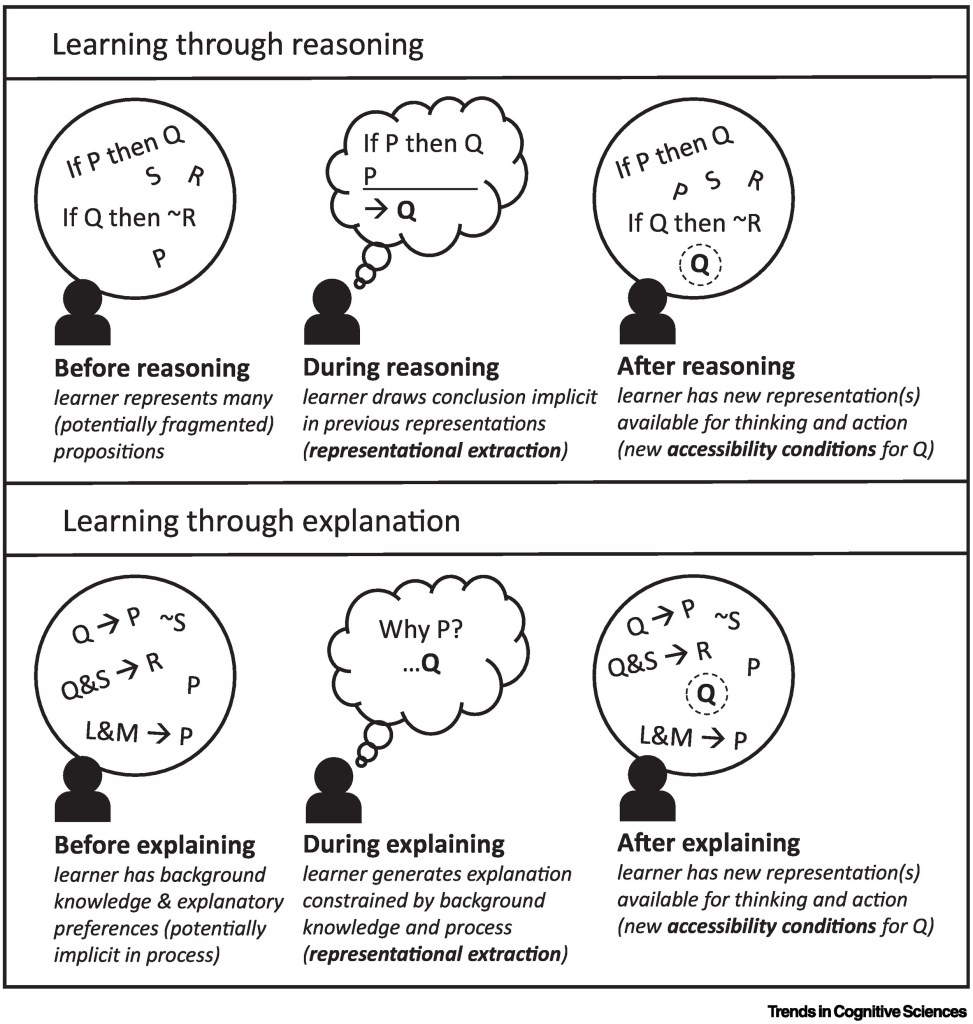

Schematic illustration of different forms of learning.

Represented are two canonical forms of learning from observation, and four examples of learning by thinking (LbT).

In each case the learner ‘learns’ the new proposition, Q.

– In one sense, learners gain no new information: they have only the elements already in their minds to work with.

– In another sense, learning has occurred: the agent has acquired new knowledge or new abilities.

One aim of this article is to suggest a resolution to this paradox. Another is to highlight the parallels between LbT across natural and artificial minds, focusing on learning through explanation, simulation, comparison, and reasoning.

Doing so reveals parallel computational problems and solutions across humans and AI: both systems make use of processes that re-represent existing information to support more reliable inferences. In so doing, LbT processes help resource limited systems like us reach relevant conclusions ‘on demand’ rather than relying exclusively on the learning that occurs when observations are first made.

Four varieties of LbT

- Learning through explanation

- Learning through simulation

- Learning through analogical reasoning and comparison

- Learning through reasoning

How can ‘thinking’ be sufficient for ‘learning’?

learning by speaking

Heinrich von Kleist

On the gradual construction of thoughts during speech

‘For it is not we who know, but at first it is only a certain state of mind of ours that knows’

On this view, the ‘learning’ in LbT comes from making some knowledge newly accessible to the learner (the ‘we’).

The reason thinking is sufficient – without external input – is because the basis for that knowledge was already in the mind (or in a ‘certain state of mind‘)

Two examples of LbT, schematically representing the role of representational extraction and its consequences for the accessibility conditions of representations. Note that LbT processes can change multiple representations; for example, explaining might not only result in the explicit representation of some explanation, Q, but also in the target of that explanation being represented at a different level of abstraction

LbT is ubiquitous: humans learn not only through observation but also through explanation, comparison, simulation, reasoning, and beyond. Recent developments reveal that AI systems can also learn in these ways. In both cases we can resolve the paradox of LbT by recognizing that representations can vary in their accessibility conditions; through LbT, representations with novel accessibility conditions can be extracted and put to use to yield new knowledge and abilities.

In one sense, LbT reflects cognitive limitations:

a system with unlimited resources and limited uncertainty would be able to work out the consequences of observations as they occur.

By contrast, natural and artificial minds face limited resources and considerable uncertainty about what will be relevant to future judgments and decisions. In such cases, LbT offers a way to support ‘on demand’ learning that capitalizes on the strengths of existing representations in

the context of the agent’s current situation and goals.

However, many questions remain open about how LbT processes are implemented in natural and artificial minds, including how they contribute to human intelligence and when they might lead us astray. Learning the answers to these questions will ultimately require more than merely thinking – it will take the full, interdisciplinary toolkit of cognitive science.