“Basic Functional Trade-offs in Cognition: An Integrative Framework” by Marco Del Giudice and Bernard J. Crespi, 2018.

Trade-offs between advantageous but conflicting properties (e.g., speed vs. accuracy) are ubiquitous in cognition, but the relevant literature is conceptually fragmented, scattered across disciplines, and has not been organized in a coherent framework.

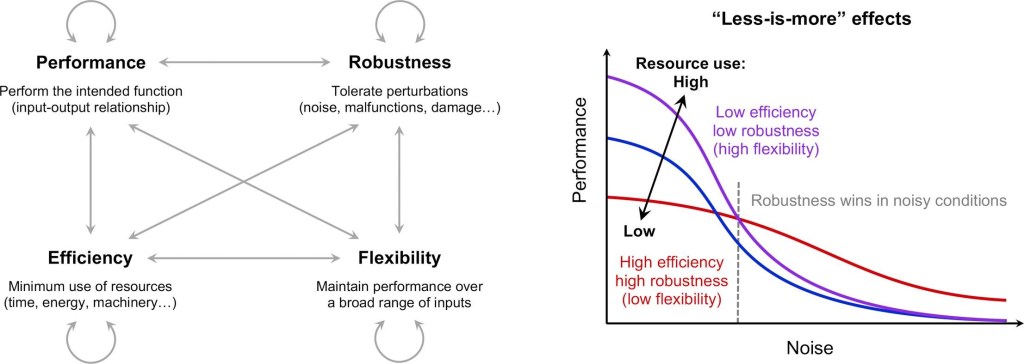

This paper takes an initial step toward a general theory of cognitive trade-offs by examining four key properties of goal-directed systems: performance, efficiency, robustness, and flexibility.

These properties define a number of basic functional trade-offs that can be used to map the abstract “design space” of natural and artificial cognitive systems. Basic functional trade-offs provide a shared vocabulary to describe a variety of specific trade-offs including speed vs. accuracy, generalist vs. specialist, exploration vs. exploitation, and many others. By linking specific features of cognitive functioning to general properties such as robustness and efficiency, it becomes possible to harness some powerful insights from systems engineering and systems biology to suggest useful generalizations, point to under-explored but potentially important trade-offs, and prompt novel hypotheses and connections between disparate areas of research.

Less-is-more effects as triple trade-offs between efficiency, robustness, and flexibility. When conditions are sufficiently noisy, robust heuristics that use limited information and computational resources systematically outperform more complex and resource- or knowledge-intensive algorithms (right side of the figure). However, such efficient and robust heuristics lack flexibility, and perform well only when matched to a specific kind of environment and/or task.

Trade-offs—balances between separately advantageous but conflicting traits—are fundamental aspects of all goal-directed systems, whether they are artificial machines or biological mechanisms designed through evolution by natural selection. Trade-offs are also ubiquitous in cognitive systems. Enhanced computational performance does not come for free; the same is true of other desirable properties such as speed, flexibility, or the ability to withstand damage.

Crucially, improving a system on one front will typically worsen it in other ways. For example, the speed of decisions can be increased by sacrificing their accuracy, and more flexible learning algorithms also tend to be more computationally demanding. The design of cognitive systems is thus shaped by constraints, compromises, and opposing priorities that can be understood only in relation to the underlying trade-offs.

basic functional trade-offs: a set of highly general trade-offs that apply to all natural or artificial systems designed to perform a function, including cognitive systems whose function can be described as manipulation of information

Broadly defined, a cognitive system is an information-processing

mechanism that computes mappings between inputs and outputs. Input-output mappings can be extremely complex; as well, outputs can take many possible forms, including commands to physical effectors but

also representations that are used as inputs to other systems (e. g., information transfer between different brain regions).

Note that we employ both “computation” and “information” in a broad sense, to include non-algorithmic and non-digital types of computation as well as various types of information.

Performance

The performance of a system is usually defined as its ability to produce an intended result (or some other roughly equivalent formulation). The concept of performance is meaningless without explicit or implicit reference to function, the idea that the system has an identifiable purpose, goal, or rationale. In turn, function implies design—in order to fulfill a purpose, a system needs to be structured in an organized, non-random fashion. When the term “design” is employed in this broad sense it does not require the existence of a conscious designer.

Cognitive systems are often arranged hierarchically, with smaller/simpler systems nested within larger/more complex ones (e.g., hierarchies of routines and subroutines in software applications; hierarchies of neural circuits in brains, down to the level of individual neurons and synapses).

Efficiency

The efficiency of a system is its ability to perform its function with minimal use of resources. Time is a vital resource, particularly in cognition: a faster system can respond more quickly to important events, make rapid decisions, and free up time for other tasks. When the activity of a system relies on the serial (as opposed to parallel) concatenation of multiple subsystems, the delays introduced by each of them will cumulate, making speed a highly desirable property.

Another crucial type of resource is energy, which is required for the operation of any natural or artificial system.

Less obviously, evolutionary simulations show that selection to minimize the cost of the connections between the elements of a network (including the necessary machinery and the energy required to run it) may be sufficient to favor the evolution of a modular organization.

Finally, complex cognitive systems often contain centralized computational resources (e.g. shared memory spaces) that can be accessed and used by multiple subsystems.

Robustness

Robustness is the ability of a system to maintain performance in the face of perturbations. There are many possible kinds of perturbations, both external (e.g., physical damage, extreme events that exceed the system’s operating range) and internal (e.g., component failures, conflicts between subsystems). Cognitive systems are particularly exposed to perturbations caused by information corruption or noise. Noise can arise at any stage in the flow of information, including the system’s input (e.g., sensors, neural connections), internal processing mechanisms, and output (e.g., inaccurate effectors), as well as in the environment in the form of stochastic fluctuations, sampling error, and unreliable cues to the true state of the world.

An especially widespread strategy to counteract perturbations is to

include feedback loops in the system. Feedback controllers track the state of the system over time, correcting discrepancies between the desired and actual state as they arise. If the behavior of the system and the effect of perturbations can be modeled with some accuracy, feedback control can be supplemented with feedforward mechanisms that anticipate disturbances and correct them proactively instead of reactively.

Finally, the potentially catastrophic impact of rare outlier events (“black swans”) can be attenuated by pessimistic decision-making strategies that are biased toward expectations of worst outcome scenarios.

Whereas robustness is defined as the ability to maintain performance

against perturbation, the concept of antifragility refers to systems that improve their performance in response to perturbations, at least within a certain range. More precisely, antifragile systems are defined as those that exhibit convex sensitivity to perturbations, so that stronger perturbations lead to disproportionally larger improvements. In a general sense, the ability to use perturbations to enhance performance is a pervasive feature of systems that learn from their failures and errors, including many cognitive systems.

Observation of natural and artificial systems indicates that, as a general rule, the more a system depends on an intricate network of communication and control mechanisms, the more it is exposed to catastrophic failure if those mechanisms fail or are hijacked. Paradoxically, systems that are especially well optimized to resist a specific kind of perturbation tend to become more vulnerable to unanticipated or rare events. The general principle that enhancing a system’s robustness against one type of perturbation often generates fragilities to other types of perturbation is summarized by the phrase “robust yet fragile”; the resulting trade-offs have been labeled robustness-fragility trade-offs.

While functional complexity can give rise to vulnerabilities, it would be a mistake to think that less complex systems are immune from robustness-fragility trade-offs. In fact, a classic case of robust-yet-fragile effect is the “conservation of fragility” in controllers based on negative feedback.

Flexibility

Of the functional properties examined in this paper, flexibility is the hardest to pinpoint with precision; even in the scientific literature the term is often employed intuitively, without an explicit definition. Generally speaking, a system or organism is regarded as flexible if it can perform in a broad range of conditions and/or successfully adjust to changes and novelties in its operating environment. For cognitive systems we suggest that flexibility can be recast as the ability to maintain performance (i.e., produce the intended input-output relationship) over a broad range of inputs, potentially including novel or unanticipated ones. We construe inputs broadly to include variation in operating conditions, domains of application, task demands, and so on.

A recurring theme in the literature is the ability to quickly update the

system’s operating parameters or stored information. For this reason, flexibility can be enhanced by accepting new inputs without filtering them, and/or by processing them in real time. Conversely, flexibility is markedly reduced when the system is controlled by feedforward processes that ignore or discount new inputs. An extreme example of the latter is offered by defensive reflexes (e.g., retracting one’s hand from a burning

object), which once triggered tend to be carried out inflexibly and with

little room for correction.

Less intuitively, slow-acting feedback processes can also stabilize a system, locking it in the current state and reducing the influence of new inputs.

There are a number of neural feedback mechanisms (e.g., facilitation by recurrent excitatory synapses) that seem to play this role in the stabilization of memory traces. At a more abstract level of analysis, investing time in exploration (vs. exploitation) may contribute to increase the future flexibility of the system by broadening the range of inputs it is exposed to, as well as gathering information that can be stored and used later to improve performance in the face of change and novelty.

Fast-and-frugal heuristics are a class of simple algorithms that make rapid decisions (fast) by discarding most of the available information and employing only a few cues from the environment (frugal).

Fast-and-frugal heuristics are defined by their efficiency; in many real-world conditions, they can outperform more complex algorithms that make full use of the available information, such as linear regression. The key to the

success of simple heuristics is their “ecological rationality:” each particular heuristic is matched to a specific kind of environment, and works by exploiting ecological regularities while avoiding overfitting (i.e., minimizing variance) by virtue of its computational simplicity.

Interestingly, recent work indicates that fast-and-frugal heuristics can themselves be outperformed by Bayesian models that use all the available information while heavily discounting some of it in order to match the structure of the environment or task, rather than discarding it altogether as heuristics do. These models are somewhat more flexible than fast-and-frugal heuristics, but markedly less efficient owing to their computational complexity.

Multiple trade-offs

Up to this point, we have focused our analysis on trade-offs between pairs of functional properties—performance versus efficiency, robustness versus flexibility, and so on. However, several of the examples we discussed involve multiple trade-offs that jointly define the system’s design constraints.

Looking at fast-and-frugal heuristics from the standpoint of functional trade-offs helps clarify a crucial but counterintuitive phenomenon.

Under the right conditions, simple heuristics can be more accurate than more complex algorithms that use all the available information, even with unlimited time and computational resources; so that increasing the amount of resources devoted to computation actually results in worse performance. This violation of the performance efficiency trade-off is an instance of what have been labeled “less-is-more effects”. The violation is

only apparent, however. The key to the superiority of fast-and-frugal heuristics lies in the combination of robustness—which boosts their performance in noisy conditions—and specialization for a particular kind of environment or task (ecological rationality). In other words, the lack of flexibility of these heuristics ultimately allows them to perform well despite their extreme efficiency.