Recent experiments have found that prompting people to think about accuracy reduces misinformation sharing intentions. The process by which this effect operates, however, remains unclear. Do accuracy prompts cause people to “stop and think,” increasing deliberation? Or do they change what people think about, drawing attention to accuracy?

Do accuracy prompts cause people to think more, or do they change what people think about (or both)?

Since these two accounts predict the same behavioral outcomes (i.e., increased sharing discernment following a prompt), we used computational modeling of sharing decisions with response time data,

as well as out-of-sample ratings of headline perceived accuracy, to test the accounts’ divergent predictions across six studies.

The results suggest that accuracy prompts do not increase the amount of deliberation people engage in. Instead, they increase the weight participants put on accuracy while deliberating.

By showing that prompting people makes them think better even without thinking more, our results challenge common dual process interpretations of the accuracy-prompt effect.

Our findings also highlight the importance of understanding how social media distracts people from considering accuracy, and provide evidence for scalable interventions that redirect people’s attention.

People often fail to attend to accuracy when making sharing decisions on social media, even though they express a preference for sharing only accurate content and can often discern true from false news when asked to evaluate content accuracy.

According to the attention account, inattention to accuracy causes

people to share misinformation unwittingly. As a result, simple accuracy prompts that redirect attention to accuracy (e.g., asking people to evaluate the accuracy of a random news headline) will increase the quality of news shared

Accuracy prompts could cause people to share higher quality news by encouraging people to deliberate more (even without increasing the relative share of attention directed to accuracy).

This deliberation account follows from the dual-process perspective wherein intuitive “System 1” processes are distinguished from analytic “System 2” processes. Merely increasing deliberation (i.e., “triggering System 2”) could increase judgment accuracy by making people question their faulty intuitions.

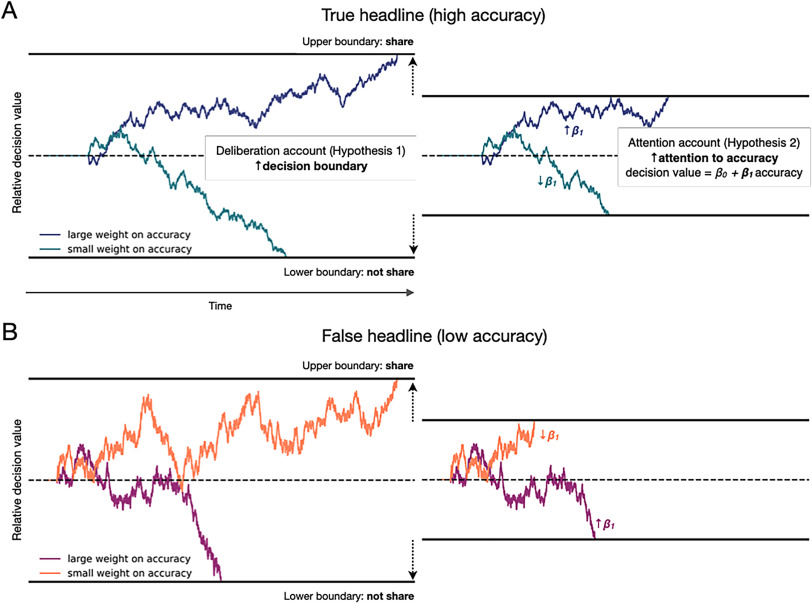

Simulated trajectories for a true (A) and false (B) headline.

Trajectories in the right panels are truncated versions (due to reduced boundaries) of the trajectories in the left panels.

The figure illustrates various simulated trajectories, which plot the relative decision value in favor of sharing (upper bound) or not sharing (lower bound) a true (Fig.A) or false (Fig.B) news headline, as a function of time during a single choice. As the participant deliberates, the decision value “drifts” toward one boundary (corresponding to a discrete choice), along a line influenced by, among other things, the headline’s perceived accuracy. A decision is made once the decision value reaches one of the boundaries.

DDMs enable us to make separable inferences about the

(i) amount of deliberation that occurs and

(ii) extent to which that deliberation is influenced by accuracy.

By decomposing the joint distributions of choices (sharing intentions) and response times into parameters that capture these different processes, DDMs allow us to more directly adjudicate between the attention and deliberation accounts of the accuracy-prompt effect.

If accuracy prompts make people deliberate more—as per the deliberation

account rooted in dual-process theories—the decision boundaries

should be larger in the accuracy prompt (vs. control) condition (Fig.

left versus right panels), allowing for more deliberation to occur before

acting (Hypothesis 1).

Alternatively, if accuracy prompts increase how much accuracy influences the trajectory of deliberation (i.e., increase accuracy’s influence on the slope along which the decision value drifts)—as per the attention account—then only weight placed on accuracy (but not the amount of deliberation) should be increased in the accuracy prompt (vs. control) condition (Hypothesis 2). In this case, true (high perceived accuracy) headlines will tend to be shared (Fig.A, blue trajectories) whereas false (low perceived accuracy) headlines will not be shared (Fig.B, magenta trajectories).

“thinking better” is different from—and perhaps more important than—“thinking more.”

Our results indicate that accuracy prompts do not work by causing people to “stop and think”, and therefore challenge common dual-process interpretations of the accuracy-prompt effect.

Moreover, it is notoriously difficult to increase deliberation.

Redirecting attention, however, might be relatively easier.

Thus, the accuracy-prompt approach may be more effective and scalable than interventions that try to increase people’s propensity to engage in analytical thinking.

For example, social media platforms could ask users to periodically consider content accuracy—particularly if platforms had reasons to believe the user is about to be exposed to misinformation.