(but it is useful to act like it does)

All of statistics and much of science depends on probability — an astonishing achievement, considering no one’s really sure what it is.

In our everyday world, probability probably does not exist — but it is often useful to act as if it does.

— David Spiegelhalter

Uncertainty has been called the ‘conscious awareness of ignorance’

Probability is not an objective property of the world, but a construction based on personal or collective judgements and (often doubtful) assumptions.

Probability was a relative latecomer to mathematics.

Iit was not until the French mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat started corresponding in the 1650s that any rigorous analysis was made of ‘chance’ events.

Meteorologists make predictions of temperature, wind speed and quantity of rain, and often also the probability of rain — say 70% for a given time and place.

The first three can be compared with their ‘true’ values; you can go out and measure them. But there is no ‘true’ probability to compare the last with the forecaster’s assessment. There is no ‘probability-ometer’. It either rains or it doesn’t.

Probability is “Janus-faced”:

it handles both chance and ignorance.

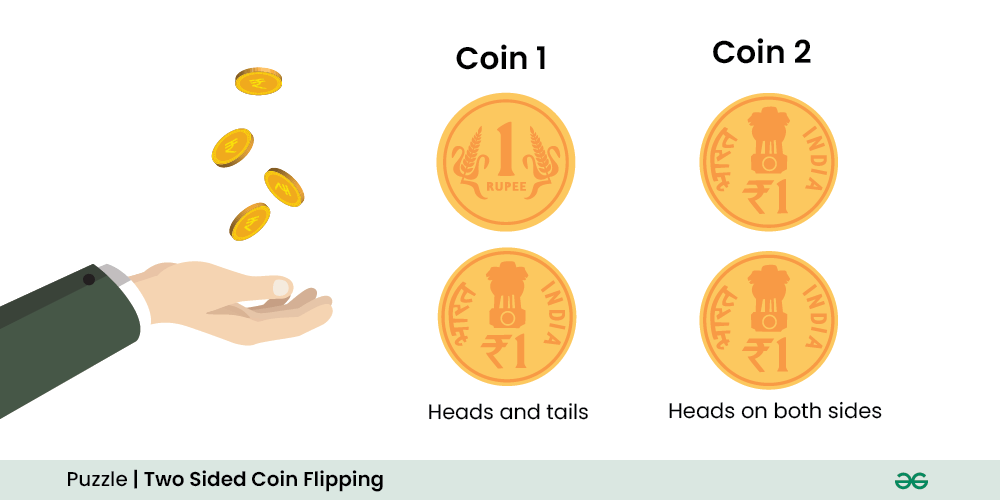

Imagine I flip a coin, and ask you the probability that it will come up heads. You happily say “50–50”, or “half”, or some other variant. I then flip the coin, take a quick peek, but cover it up, and ask: what’s your probability it’s heads now?

Note that I say “your” probability, not “the” probability. Most people are now hesitant to give an answer, before grudgingly repeating “50–50”. But the event has now happened, and there is no randomness left — just your ignorance.

The situation has flipped from ‘aleatory’ uncertainty, about the future we cannot know, to ‘epistemic’ uncertainty, about what we currently do not know. Numerical probability is used for both these situations.

Even if there is a statistical model for what should happen, this is always based on subjective assumptions.

Any practical use of probability involves subjective judgements.

The objective world comes into play when probabilities, and their underlying assumptions, are tested against reality (see ‘How ignorant am I?’); but that doesn’t mean the probabilities themselves are objective.

“all models are wrong, but some are useful”

— Box, J. E. P., 1976, J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 71, 791–799.

frequentist probability: an approach that defines the theoretical proportion of events that would be seen in infinitely many repetitions of essentially identical situations.

It does not make sense to think of our judgements as being estimates of ‘true’ probabilities. These are just situations in which we can attempt to express our personal or collective uncertainty in terms of probabilities, on the basis of our knowledge and judgement.

How do we define subjective probability?

The laws of probability can be derived simply by acting in such a way as to maximize your expected performance when using a proper scoring rule, such as the one shown in “How ignorant am I?”.

Alan Turing uses the working definition that “the probability of an event on certain evidence is the proportion of cases in which that event may be expected to happen given that evidence”.

This acknowledges that practical probabilities will be based on expectations — human judgements.

But by “cases”, does Turing mean instances of the same observation, or of the same judgements?

“probability does not exist”

— Bruno de Finetti, Theory of Probability

A sequence of events is judged to be exchangeable if our subjective probability for each sequence is unaffected by the order of our observations. De Finetti brilliantly proved that this assumption is mathematically equivalent to acting as if the events are independent, each with some true underlying ‘chance’ of occurring, and that our uncertainty about that unknown chance is expressed by a subjective, epistemic probability distribution. This is remarkable: it shows that, starting from a specific, but purely subjective, expression of convictions, we should act as if events were driven by objective chances.

‘How ignorant am I‘

The need to evaluate the accuracy of the probabilities people assign to things became clear when weather forecasters started giving probabilities of precipitation.

In 1950, meteorologist Glenn Brier developed the Brier score to assess predictions, and it can be adapted to check how good, or how bad, you are at assessing your degree of confidence about facts.

Any positive score indicates some degree of awareness about your own knowledge level. If your score was negative, you are supremely overconfident.

A good Brier score depends on a probability assessor both being discriminatory, so they give some confident judgements, but also calibrated, so that, of the situations in which they state a ‘70% probability’, they are right around 70% of the time. This idea turns out to be fundamentally important when we consider the meaning of these subjective judgements.

With each of the following questions, decide which answer you feel is most likely to be correct, and then quantify your confidence on a scale from 5 to 10. For example, if you are certain that answer is correct, you should give it 10/10, but if you are only around 70% sure, then it gets 7/10. If you have no idea, then give 5/10 to either choice.

The scoring is deliberately harsh (in technical terms, it is based on the square of the prediction error). By punishing failure more than rewarding success and giving a steep penalty for being confident and wrong, honesty is encouraged.

People with an exaggerated sense of their own knowledge tend to end up with large negative scores. Those with an awareness of their own doubts tend to mainly use 5s, 6s or 7s, and might end up with a small positive score. People who actually know a lot, or are extremely lucky, get higher scores. This type of exercise is used to train forecasters to be less overconfident, and to gain insight into their own thought processes.

| Score table: Confidence | Score if you are right | Score if you are wrong |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 9 | 11 |

| 7 | 16 | 24 |

| 8 | 21 | 39 |

| 9 | 24 | 56 |

| 10 | 25 | 75 |

Since being uncertain is part of being human, can we learn to live with it? Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman claimed, “I’m smart enough to know I’m dumb”, and was comfortable with not fully understanding things, saying: “I can live with doubt, uncertainty and not knowing.”

This sets a fine example for how to deal with the inevitable ignorance in our lives.

In the end we have to admit we are ignorant of so much and just learn to live with it.

The Art of Uncertainty: How to Navigate Chance, Ignorance, Risk and Luck by David Spiegelhalter discusses how to navigate uncertainty in an unpredictable world. A statistician offers a masterful guide to embracing the unknown.

Uncertainty is thus not an intrinsic property of events, Spiegelhalter writes, but rather a reflection of the knowledge, perspective and assumptions of the person trying to understand or predict those events. It varies from person to person and situation to situation, even when the circumstances are identical. It is subjective and shaped by what we know or don’t know at a given time.

Spiegelhalter distinguishes two main types of uncertainty:

– aleatory uncertainty, that which we cannot know, and

– epistemic uncertainty, that which we do not know.

Understanding this distinction is crucial for making informed decisions. Whereas aleatory uncertainty is often irreducible, epistemic uncertainty can be minimized through better data collection, refined models or deeper investigation.

A central theme woven throughout Spiegelhalter’s book is the importance of humility in prediction.