“Defining intelligence: Bridging the gap between human and artificial perspectives“

- Proposes unified definitions for human and artificial intelligence.

- Distinguishes between artificial achievement/expertise and artificial intelligence.

- Advocates for AI metrics to ensure good quality AI system evaluations.

- Describes artificial general intelligence (AGI) mirroring human general intelligence.

- Evidence currently favours presence of artificial achievement over intelligence.

Achieving a widely accepted definition of human intelligence has been challenging, a situation mirrored by the diverse definitions of artificial intelligence in computer science.

By critically examining published definitions, highlighting both consistencies and inconsistencies, this paper proposes a refined nomenclature that harmonizes conceptualizations across the two disciplines. Abstract and operational definitions for human and artificial intelligence are proposed that emphasize maximal capacity for completing novel goals successfully through respective perceptual-cognitive and computational processes.

Additionally, support for considering intelligence, both human and artificial, as consistent with a multidimensional model of capabilities is provided. The implications of current practices in artificial intelligence training and testing are also described, as they can be expected to lead to artificial achievement or expertise rather than artificial intelligence. Paralleling psychometrics, ‘AI metrics’ is suggested as a needed computer science discipline that acknowledges the importance of test reliability and validity, as well as standardized measurement procedures in artificial system evaluations.

Drawing parallels with human general intelligence, artificial general intelligence (AGI) is described as a reflection of the shared variance in artificial system performances.

We conclude that current evidence more greatly supports the observation of artificial achievement and expertise over artificial intelligence.

Models of intelligence and g

In psychology, general intelligence (g) is a theoretical construct postulated to account for the empirical observation that test scores from a diverse collection of intelligence tests tend to correlate with each other positively. In practical terms, people who tend to perform relatively well on verbal tasks also tend to perform relatively well on spatial tasks, memory span tasks, quantitative tasks, etc.

Arguably, the most commonly recognised model of intelligence is the Cattell-Horn-Carroll model (CHC), a comprehensive framework that integrates a wide range of cognitive abilities.

The CHC model categorises abilities across three strata, each representing a different level, or breadth, of cognitive functioning.

- At stratum I are abilities that are narrow in nature, representing specific cognitive tasks and processes. Examples include induction (I), reading comprehension (RC), spatial relations (SR), and working memory (MW).

- Stratum II is the intermediate level and consists of relatively broad cognitive abilities in comparison to those abilities of Stratum I. Stratum II abilities arise because of relatively highly-correlated clusters of narrow stratum I abilities. In addition to the relatively well-known fluid reasoning factor (Gf), there are four factors that represent acquired-knowledge abilities, including comprehension–knowledge (Gc), domain-specific knowledge (Gkn), reading and writing (Gw), and quantitative knowledge (Gq). There are five specific sensory abilities, including visual (Gv), auditory (Ga), olfactory (Go), tactile (Gh), and kinesthetic (Gk). There are three memory factors, including working memory capacity (Gwm), learning efficiency (Gl), and retrieval fluency (Gr). There are also three speed-relevant abilities, including reaction/decision time (Gt), processing speed (Gs), and psychomotor speed (Gps). Finally, there is a psychomotor ability factor (Gp).

People who have high reasoning ability (Gf) also tend to have higher levels of comprehension-knowledge (Gc), for example. - Finally, stratum III is the top level, representing general intelligence or ‘g’. It may be considered a representation of overall cognitive ability. To date, there are two approaches to the representation of general intelligence:

(1) g as superordinate factor; and

(2) g as breadth factor.

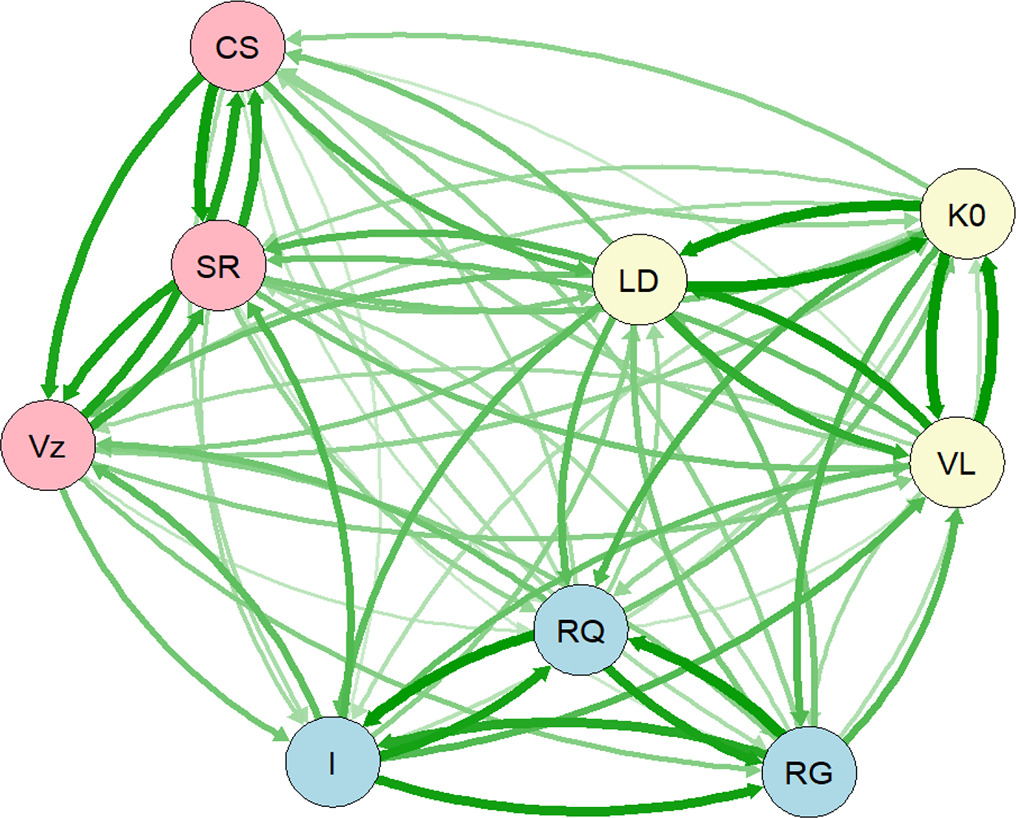

Note. CS = closure speed; SR = spatial relations; Vz = visualization; I = induction; RQ = quantitative reasoning; RG = general sequential reasoning; LD = language development; K0 = general (verbal) information; VL = lexical knowledge; mauve coloured circles represent fluid reasoning abilities (Gf);

yellow coloured circles represent comprehension knowledge abilities (Gc);

blue coloured circles represent visual intelligence abilities (Gv).

Like intelligence, learning is a construct:

it is not observed directly, but inferred from the observation of inter-related behaviours. Human learning may be defined as a demonstrable change in the probability or intensity of a specific behaviour or behaviour potential, underpinned by neurological processes and cognitive strategies in response to various stimuli. This change excludes factors unrelated to learning, such as instinct or physical maturation.

By comparison, AI learning may be defined as a demonstrable change in the probability or intensity of a specific response or decision-making potential in an artificial system, underpinned by computational algorithms and data. This change excludes factors unrelated to learning, such as programming updates or hardware modifications.

Our complementary definitions of learning emphasize the role of the probability of responses in both human and AI domains, while also accounting for the distinct nature of learning in each domain.

Within the CHC model of intelligence, learning represents only a relatively small facet of the model.

Learning is represented by a relatively small stratum II ability known as a learning efficiency (Gl), a dimension that represents “how much time and effort is needed to store new information in secondary memory [e.g., long-term memory]”. Associative memory is considered an indicator (stratum I ability) of learning efficiency (Gl). A commonly used test of associative memory consists of face-name pairings. In face-name pairings test, participants first view a series of face-name pairs and then, in the test phase, they are shown the faces again and asked to recall the associated names. This assesses their ability to form and retrieve associations, reflecting their learning efficiency in encoding and storing associative information in long-term memory. As the visual processing capacities of AI systems develop, their associative memory capacity could be measured with the validated face-name pairing test.

In addition to associative memory, meaningful memory is considered an indicator of Gl. Meaningful memory refers to the ability to remember information that is significant and conceptually rich, as opposed to rote memorization of arbitrary or unrelated facts. A psychometrically established measure of meaningful memory is the Story Recall subtest. In the Story Recall test, participants are presented with a prerecorded short prose story, typically one to three paragraphs in length.

Research indicates that higher general intelligence enhances learning outcomes, with more intelligent individuals showing better responses to training. Furthermore, having more prior knowledge (Gk) also improves learning on new tasks.

A remarkable instantiation of human learning is the acquisition of language, a capacity that develops rapidly from infancy. Furthermore, typically developing children acquire complex linguistic structures with minimal instruction – a stark contrast to AI’s need for extensive data and iterative training to achieve somewhat comparable concept formation.

AI systems have demonstrated their capability to solve cognitive ability test problems, primarily through guided training or programmed approaches to transform problems into algorithmically solvable formats. While remarkable, it is debatable whether these accomplishments signify intelligence, given that the capabilities of most current AI systems are limited to specific programming and/or training data, without the necessary demonstration of novel problem-solving ability characteristic of human intelligence.

Consequently, many AI systems might be more aptly recognised as having the capacity to exhibit artificial achievement or artificial expertise. Despite not reaching the threshold of artificial intelligence, artificial achievement and expertise systems should, nonetheless, be regarded as remarkable scientific accomplishments, ones that can be anticipated to impact many aspects of society in significant ways.

Furthermore, with clear and coherent conceptualisations and definitions of achievement, expertise, intelligence, and general intelligence adopted by the fields of psychology and computer science, greater collaborations and insights may be facilitated, which may ultimately help bridge the gap between artificial and human-like intelligence.