Every few seconds, our visual world disappears behind a thin fold of skin that maintains the tear film on the corneal surface and, for more than a tenth of a second, blocks light from falling onto the retina. “Blink and you miss it” is a common idiom that captures how we have conceived of those moments in time. A new study now turns this idea on its head, showing that the transients caused by blinks effectively enhance visual contrast sensitivity. The authors argue that these movements are a computational component, not an inconvenience, of visual processing.

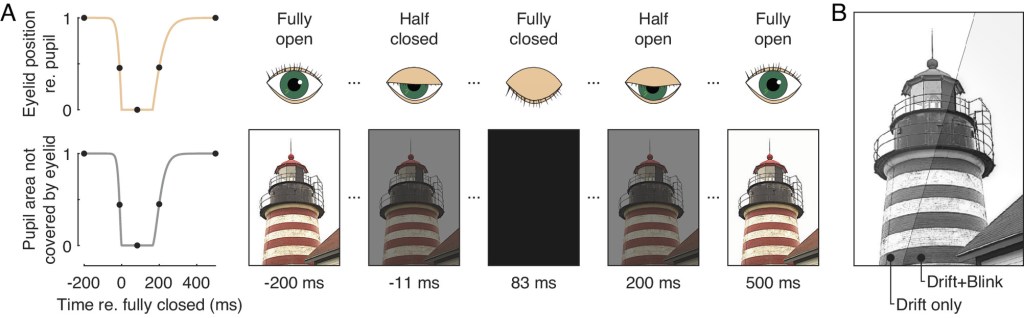

(A) Following measurements of the dynamics of eyelid closure, the study modeled the pupil area not covered by the eyelid. An example image highlights the amount of light reaching the retina in different blink phases (time points correspond to black dots in the leftmost panels).

(B) Schematic depiction of the visual benefit resulting from a blink—an enhancement of luminance contrast emphasizing lower spatial frequencies while leaving high spatial frequencies unaffected.

Eye blinks would, in principle, increase the power across a wide range of spatial and temporal frequencies. But because fixational eye movements cause incessant transients in the range of high-spatial frequencies, the luminance variations resulting from eye blinks would most strongly affect visibility of stimuli with wider-spaced luminance variations (spatial frequencies lower than 5 cycles per degree).

the major transients that blinks impose on the visual input effectively enhance sensitivity to luminance contrast for a wide range of medium to low spatial frequencies.

It is known that humans strategically select periods of time for blinking during which a momentary loss of vision is least critical—in expectation of behaviorally relevant information or in between scenes in the narrative of movies. In a similar vein, blink rates transiently break down in response to the appearance of salient stimuli.

It becomes clearer that the sudden and rapid changes in retinal input that result from these movements are a feature, not a bug, that affects visual processing in efficient ways

Concluding remark from the related study (Eye blinks as a visual processing stage): “In sum, we have shown that the luminance transients resulting from eye blinks enhance contrast sensitivity to low spatial frequencies, an effect that occurs despite the loss of exposure imposed by the blink itself. Thus, in addition to lubricating the eye, blinks also appear to serve an information-processing function by shaping the spatial content of the signals that fall within the temporal range of visual sensitivity. It is known that humans plan blinks to avoid missing salient events.”