“Is bad philosophy holding back physics?“

Carlo Rovelli states:

“My hunch is that it is at least partly because physicists are bad philosophers. Scientists’ opinions, whether they realize it or not (and whether they like it or not), are imbued with philosophy. And many of my colleagues — especially those who argue that philosophy is irrelevant — have an idea of what science should do that originates in badly digested versions of the work of two twentieth-century philosophers: Karl Popper and Thomas Kuhn.

From Kuhn comes the idea that new scientifictheories are not grounded in previous ones: progress instead comes about through ‘paradigm shifts’, the scientific equivalents of revolutions.

Popper, meanwhile, supplies the notion that a theory is scientific only if it is ‘falsifiable’: if it can be proved wrong by empirical evidence.

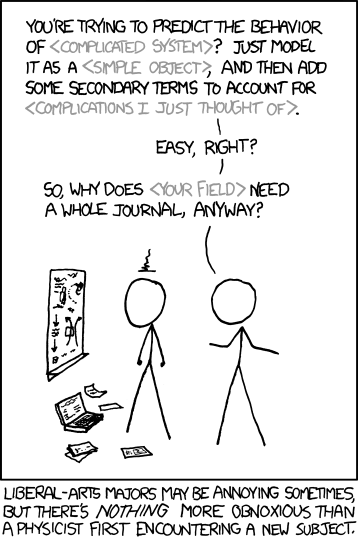

Superficial readings of Popper and Kuhn, I think, have encouraged several assumptions that have misled a good deal of research: one, that past knowledge is not a good guide for the future and that new theories must be fished from the sky; and two, that all theories that have not yet been falsified should be considered equally plausible and in equal need of being tested.

The history of science suggests that such attitudes are wrong-headed. It is difficult, if not impossible, to think of a major advance in fundamental physics that has emerged from arbitrary hypotheses. They have instead come from two sources, both empirical.

The first is new data. ….

The second source of advances is the study of apparent inconsistencies or incoherencies in established knowledge: taking this knowledge seriously, and trying to make it consistent. … “

“It is almost impossible to think of a major advance in physics that has emerged from arbitrary hypotheses.”

‘Revolutions’ in the history of fundamental physics are thus more conservative than they are often depicted.

Kuhn’s emphasis on discontinuity has led many scientists to devalue the relevance of past knowledge in making sense of what we do not yet know.

Popper’s emphasis on falsifiability, meanwhile, originally intended only as a criterion for demarcating a scientific theory, has been misinterpreted as legitimizing the idea that all speculation is equally plausible.

“The new physics was again born from previous knowledge — from taking it seriously as reliable information about reality.”

… some reflection on methodology is due.

… there are two clear open challenges for fundamental physics.

One comes from observational data: the unknown nature of dark matter.

The other comes from the incompletenessof current physics: the lack of an agreed account of what happens in situations in which the quantum aspects of gravity cannot be disregarded.

There is a healthy sense of crisis in fundamental theoretical physics. Crises are good because they make scientists question underlying assumptions and approaches. It has at times been fashionable to say in theoretical physics that there is a lack of sufficiently wild, completely new ideas. But perhaps the problem is physicists running too much after wild new ideas. New knowledge will come when new data are shown truly not to fit with what we know; or by reflecting in depth on what established theories, such as general relativity and quantum theory, imply when taken together.