“Top-down and bottom-up neuroscience: overcoming the clash of research cultures“

As scientists, we want solid answers, but we also want to answer questions that matter.

Yet, the brain’s complexity forces trade-offs between these desiderata, bringing about two distinct research approaches in neuroscience that we describe as ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’.

Bottom-up neuroscience

The bottom-up research culture cares primarily about building knowledge from firm foundations and drives progress through systematic accumulation of solid evidence and increasing detail. Accordingly, bottom-up approaches emphasize careful experimental design for studying neuroscientific scenarios by keeping everything as controlled as possible. When this cannot be achieved, researchers are willing to revise the definition of their object of study until it becomes amenable to full experimental control — thereby prioritizing a less direct but safer path to address the ‘big’ questions by breaking them down into more manageable parts.

Examples of bottom-up research include the tightly controlled experiments in the Nobel prize-winning work of Eric Kandel, whose team operationalized memory as habituation to repeated prodding in a sea slug, Aplysia californica. By accepting this — arguably drastic — simplification, Kandel’s team were able to leverage the exquisite experimental accessibility of Aplysia, characterising synaptic long-term potentiation with unprecedented detail.

Top-down neuroscience

In contrast to the bottom-up culture, the top-down research culture is driven by the desire to work on ‘big’ questions directly, with less willingness to swap the object of study for more tractable surrogates.

However, the price for directly addressing ‘big’ questions rather than more tractable substitutes is that top-down researchers often have to tolerate more uncertainty in their investigations and their outcomes, as experimental and analytical tools are often inadequate to fully capture the richness of big-picture questions. Thus, top-down approaches usually start from approximate attempts at an answer that are then progressively refined, with the details added later — rather than thoroughly answering a simplified question and then expanding it. Accordingly, top-down approaches sometimes follow hard-to-anticipate intuitions that go beyond the next logical step.

A paradigmatic example is physicist Ludwig Boltzmann’s work: while their ground-breaking results were correct, Boltzmann’s often incomplete arguments sometimes appeared as ‘logical jumps’. Network neuroscience also exemplifies successful work based on top-down principles: by emphasizing fundamental properties that the brain shares with other networked systems (for example, cities and social networks), network neuroscience has become a flourishing neuroscientific subfield, bridging scales and promoting translational discovery.

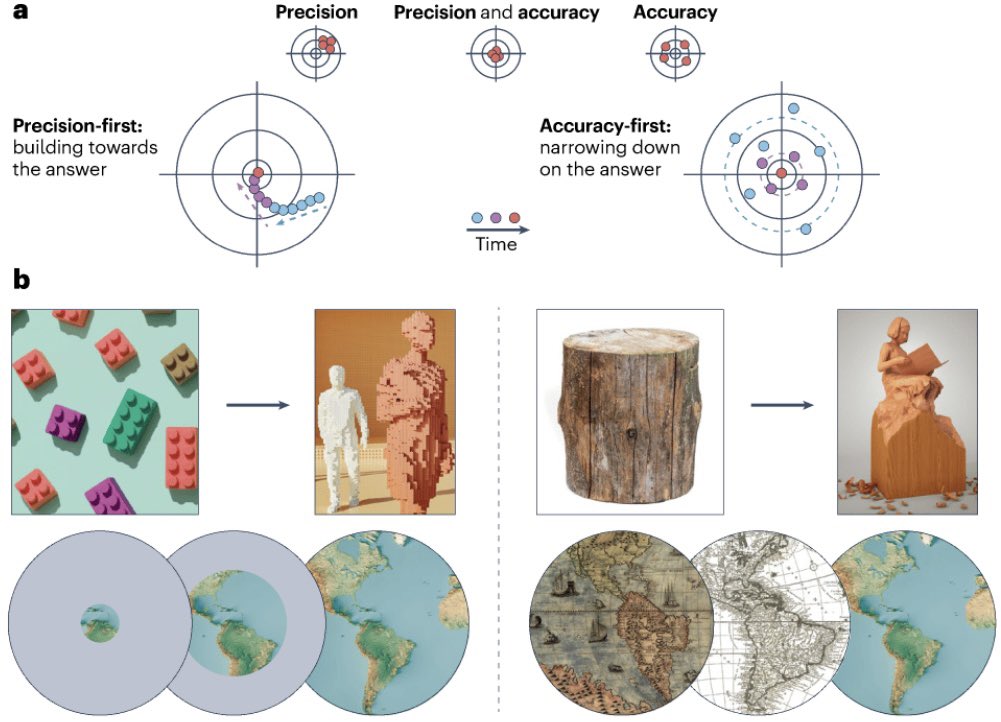

a, Precision and accuracy (or bias and variance) from statistics. Precision means that hits are closely clustered. Accuracy means that hits are centred around the true target. For bottom-up neuroscience, ‘hits’ will be close to each other at every step of the way (high precision), but the starting point may be far from the ultimate target (low initial accuracy). Top-down neuroscience goes for the desired target right away, but its tools may initially be inadequate, resulting in wide dispersion (low precision) but more focus around the target itself (higher accuracy).

b, Analogies from art and cartography. In art (top), bottom-up approaches build from the parts to the whole; top-down strategies start with a barely specified whole and develop it until the figure within becomes apparent. In cartography, bottom-up approaches can be seen as building maps by carefully charting one patch of land at a time, moving on to the next only when one is complete; top-down approaches resemble the ancient cartographers, providing a large-scale picture that is initially coarse, with the details filled in later.

Consilience and synthesis: concrete actions for progress

Ultimately, science is about rational, evidence-based resolution of disagreement, and this process is more productive if we understand why we disagree. This is why we have devoted much of this piece to explaining the values and motivations of each research culture. We urge neuroscientists to acknowledge that others may have good-faith disagreements about what counts as ‘making progress’.

Respecting the value of each research culture calls for more than mere lip-service. Concretely, reviewers, grant-makers and hiring committees should refrain from imposing their preferred meaning of scientific progress when evaluating others’ work. Instead, a fair critique should acknowledge that there can be different but equally valid ways of contributing to progress. The understanding that there are different but equally valid meanings of scientific progress should be passed on to trainees. While it is fair to teach one’s approach to one’s students, it is a disservice — to those students and the broader neuroscience community — to act as though that approach is the only valid one.

These are concrete actions that every individual neuroscientist can take to reduce unnecessary conflict arising from a simple but pervasive misunderstanding.

Furthermore, a synthesis between these different research cultures can bring about tangible progress. Concretely, computational modelling provides one fruitful avenue for achieving this synthesis (although certainly not the only avenue). Coming up with a viable model that can actually be implemented forces the top-down neuroscientist to ensure that theories remain concrete and testable. Conversely, model-development forces the bottom-up neuroscientist to confront the bigger picture by drawing a line between (putatively) necessary and unnecessary details, whose relevance is then demonstrated or refuted by the model’s performance. Models can then integrate data and knowledge across different scales and domains of neuroscience: for example, modelling the effects of pharmacological interventions by enriching one’s macroscopic model with biological detail about receptors. It can be especially valuable to engage in this modelling exercise with colleagues from the ‘other culture’, as the model represents a tangible output that grounds discussions by demanding convergence — combining the virtues of both research cultures.

In summary, as scientists we want our answers to be correct, and we also want to answer questions that matter. When these two desiderata pull in different directions, we need to decide how to weigh them. We advocate for transitioning away from the current pervasive but unacknowledged dichotomy and towards a more constructive mindset in which different dimensions of progress in neuroscience are explicitly acknowledged and their value is recognized — to temper their respective limitations and build on each other’s strengths.