- Computational models should explain both similarities and differences between species.

- Most aspects of neural function are broadly shared across species.

- Single neurons are complex computational devices, with a tree-like form.

- “Dendrophilia” – our proclivity for tree structures – is central to human cognition.

Progress in understanding cognition requires a quantitative, theoretical framework, grounded in the other natural sciences and able to bridge between implementational, algorithmic and computational levels of explanation.

This review article reviews recent results in neuroscience and cognitive biology that, when combined, provide key components of such an improved conceptual framework for contemporary cognitive science. Starting at the neuronal level, It first discusses the contemporary realization that single neurons are powerful tree-shaped computers, which implies a reorientation of computational models of learning and plasticity to a lower, cellular, level.

It then turns to predictive systems theory (predictive coding and prediction-based learning) which provides a powerful formal framework for understanding brain function at a more global level. Although most formal models concerning predictive coding are framed in associationist terms, modern data necessitate a reinterpretation of such models in cognitive terms: as model-based predictive systems.

Finally, it reviews the role of the theory of computation and formal language theory in the recent explosion of comparative biological research attempting to isolate and explore how different species differ in their cognitive capacities. Experiments to date strongly suggest that there is an important difference between humans and most other species, best characterized cognitively as a propensity by our species to infer tree structures from sequential data. Computationally, this capacity entails generative capacities above the regular (finite-state) level; implementationally, it requires some neural equivalent of a push-down stack. This unusual human propensity is dubbed “dendrophilia”, and makes a number of concrete suggestions about how such a system may be implemented in the human brain, about how and why it evolved, and what this implies for models of language acquisition.

It concludes that, although much remains to be done, a neurally-grounded framework for theoretical cognitive science is within reach that can move beyond polarized debates and provide a more adequate theoretical future for cognitive biology.

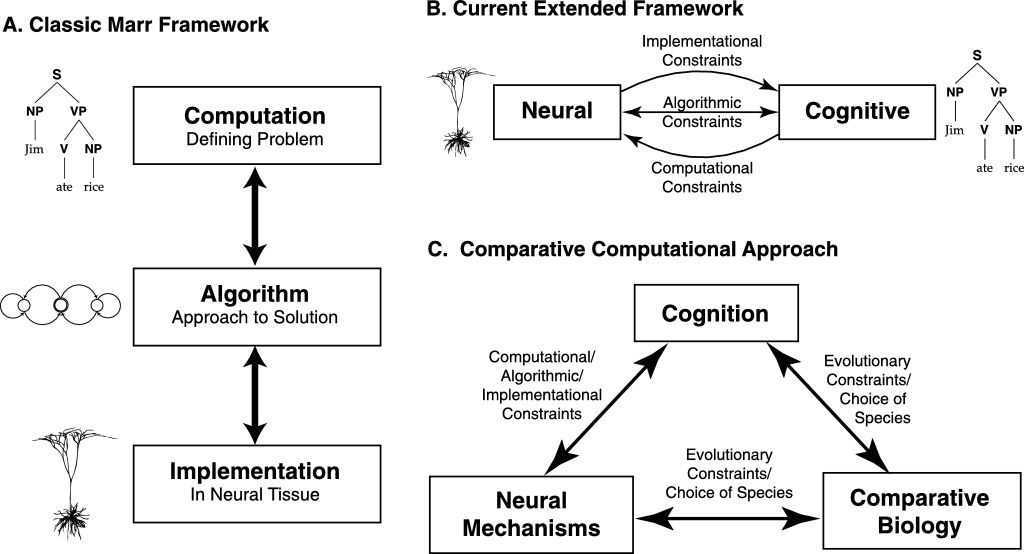

contrasted with the approach developed in the current paper (B and C).

The point of departure will be Marr’s tri-partite approach to vision (Fig. 1A), which advocates separate specifications of the problem (what Marr terms “computation”), of the problem-solving approach (“algorithm”), and of algorithmic instantiation in neural circuitry (“implementation”).

But rather than mapping the three disciplines onto Marr’s hierarchy of computation/algorithm/implementation, I will suggest that each interdisciplinary bridge must incorporate explanations at each Marrian level. My notion of “computation” is thus more fundamental, and more pervasive, than Marr’s, and goes beyond simply “stating the problem” to incorporate all that modern computer science has to teach about which problems are simple, challenging, or intractable, and about what classes of algorithms can solve each type. Thus, although the framework outlined here accepts the importance of Marr’s explanatory levels as originally described, I call for a revision in the manner in which they are used, and I argue against the now standard separation of computational accounts from implementational ones (Fig. 1B). Instead, the insights of modern computer science permeate all three of Marr’s levels, and his conception of “computational theory” was too narrow and confined to the most abstract level.

The general structure of the computational framework I advocate here is shown in Fig. 1C, which illustrates the need for productive interdisciplinary bridges between three disciplines, to form the vertices of a “computational triangulation” approach. The first two vertices are no surprise: the neurosciences and the cognitive sciences. Building bridges between these two domains is the traditional “grand challenge” of cognitive science of Fig. 1B, to bridge the apparent gap between brain and mind. However, the third, comparative, vertex traditionally plays a minor role in cognitive science. But to fully leverage the importance of algorithmic and implementational insights in constraining cognitive theories, species differences in cognition need to be identified and understood.

I suggest that modern biology should play a central role this overall bridge-building enterprise, not least because of the impressive progress in comparative neuroscience and animal cognition made in the last few decades.