“Mapping interactions between adversity and neuroplasticity across development”

Highlights:

- We propose a theoretical framework to formalize major ways in which experience (particularly adversity) interacts with neuroplasticity during human development.

- Adversity can uniquely influence neural circuitry depending on the state of neuroplasticity during the developmental timing of exposure (i.e., neuroplasticity as a moderator).

- Neuroplasticity is itself sensitive to experience. Adversity can accelerate or delay its developmental course, as well as amplify or dampen its magnitude (i.e., neuroplasticity as an outcome).

- Longitudinal designs with multimodal indicators of neuroplasticity are required to understand consequences for behavior, cognition, and psychiatric risk.

The human brain undergoes a protracted course of development that provides prolonged opportunities to be sculpted by experience. Yet, persistent definitional and measurement challenges have complicated efforts to understand how experience interacts with neuroplasticity during human development. Here, we synthesize previously siloed perspectives to propose an integrative framework defining key dimensions along which adversity interacts with neuroplasticity. We discuss how the state of neuroplasticity during the timing of exposure may modulate how adversity shapes brain development. We also outline how adversity may accelerate or delay the timing of neuroplasticity and amplify or dampen its magnitude. Identifying how, where, and when experience calibrates the brain’s capacity for change may inform how neuroplasticity dynamics can be harnessed to promote healthy development.

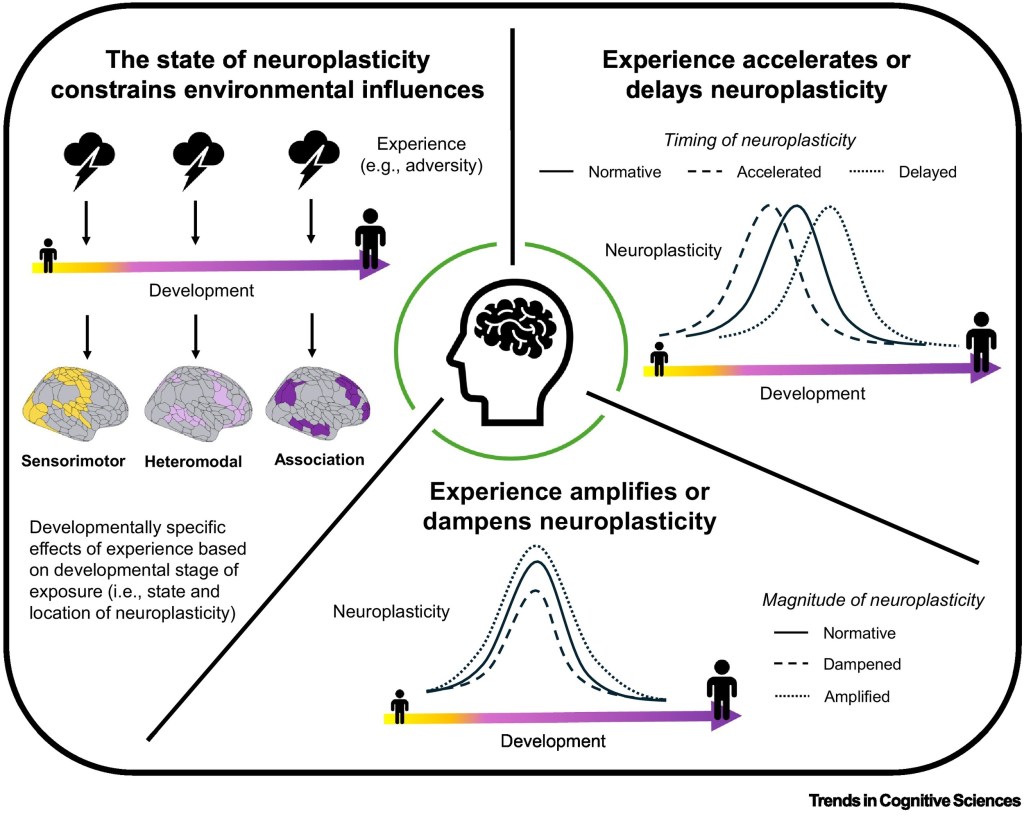

Conceptual representation of the three proposed dimensions along which experience interacts with neuroplasticity across childhood and adolescence. The state of neuroplasticity constrains environmental influences: the same environmental experience (e.g., adversity, nurturance) may influence different neurobiological properties and circuits, and ultimately cognitive and affective functions, depending on the state of neuroplasticity during the timing of exposure. Experience accelerates or delays neuroplasticity: experience can shift the timing of neuroplasticity by either accelerating or delaying the pace of brain maturation and, consequently, neuroplasticity progression. Such shifts may also extend or shorten the duration of neuroplasticity, although these dynamics are not illustrated here for parsimony. Experience amplifies or dampens neuroplasticity: experience can modulate the magnitude of neuroplasticity by either amplifying or dampening its extent.

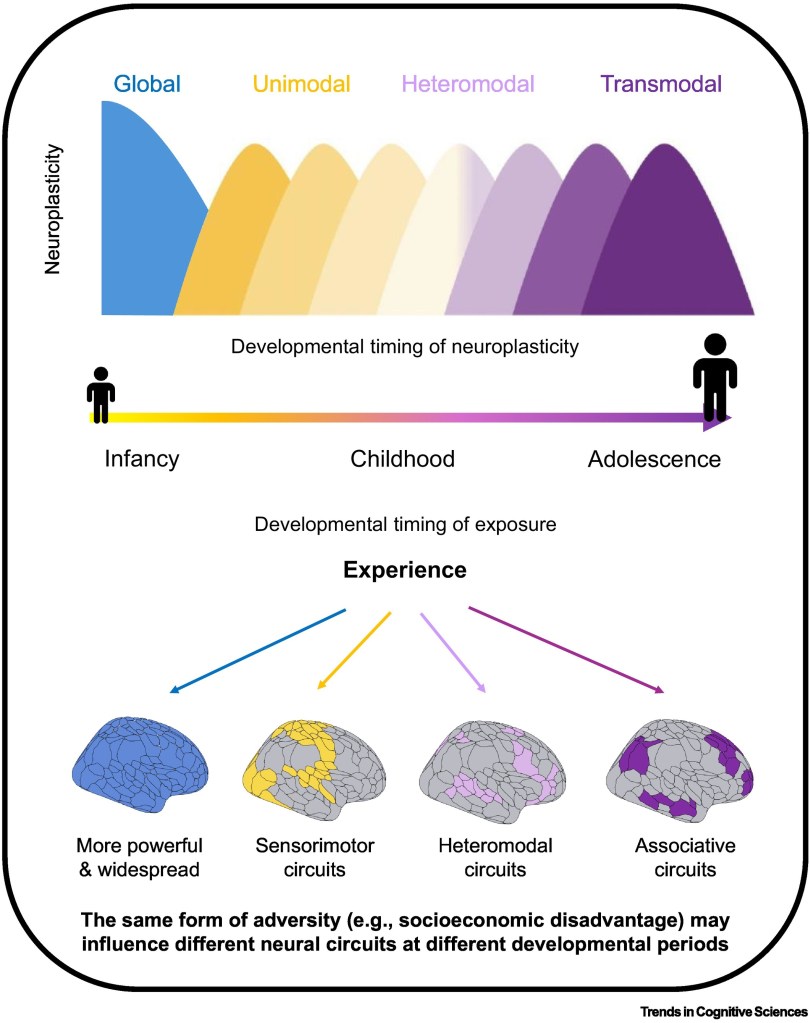

Theoretical illustration depicting how the biological embedding of experience may differ depending on the state of neuroplasticity during the developmental timing of exposure. During infancy and early childhood, neuroplasticity appears to be globally elevated across the entire brain. After early childhood, neuroplasticity may decline at the global scale and increase at the local scale to facilitate circuit-specific refinements in response to experience. Specifically, across childhood and adolescence, a recent neurodevelopmental model charts how neuroplasticity may progressively unfold from unimodal to heteromodal to transmodal circuits. Experience may consequently exert more widespread and powerful effects on neurodevelopment during early childhood relative to later developmental periods. After early childhood, experience may exert more powerful effects on neural circuits that are engaged by the specific experience and exhibit the highest neuroplasticity during the developmental timing of exposure. These neuroplasticity dynamics may therefore filter experience to influence behavior, and risk for psychopathology, through biologically- and developmentally-dependent pathways.

In this review, we propose a framework with three organizing dimensions along which adversity interacts with neuroplasticity during human development: (i) the state of neuroplasticity modulates adversity’s effects on development, (ii) adversity accelerates or delays neuroplasticity, and (iii) adversity amplifies or dampens neuroplasticity.

The first dimension explicates how the state of neuroplasticity (i.e., which circuit is most plastic) during the timing of exposure modifies how adversity becomes neurobiologically embedded, as reviewed for global-to-local and limbic-to-prefrontal scales. Importantly, early-maturing circuits and cognitive processes hierarchically orchestrate the development of later-maturing circuits and cognitive processes. Experience, brain, and behavior must consequently be measured longitudinally across multiple timepoints to elucidate how neuroplasticity shapes biobehavioral embedding. Additionally, we focus on the developmental timing of adversity given its relevance for neuroplasticity. However, the recency and accumulation of experience likely also influence neurodevelopment. Parsing this heterogeneity is essential for delineating how experience interacts with neuroplasticity.

Second, we outline how adversity may shift the timing of neuroplasticity earlier or later in development (or extend or shorten its duration). Nevertheless, several questions remain. Do differences in brain maturation reflect the same trajectory that is accelerated or delayed, or merely a distinct trajectory with unique milestones? Which types of adversity induce accelerated versus delayed versus qualitatively different trajectories of neurodevelopment? Are different proxies of neurodevelopmental pace measuring the same process, or are they tapping slightly distinct patterns, resulting in mixed findings? Do deviations in the pace of neurodevelopment indeed shift the timing of neuroplasticity? Longitudinal designs from infancy through early adulthood are needed to confirm whether trajectories, peaks, and endpoints of neuroplasticity are similar but differ in timing (i.e., accelerated/delayed maturation), duration (i.e., shorter/longer neuroplasticity windows), or are qualitatively distinct.

Third, we review indicators of myelination, intrinsic activity, and glutamatergic tone to characterize how adversity may amplify or dampen neuroplasticity. Other measures sensitive to neuroplasticity include more myelin-specific indices from mean apparent propagator models and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging, and excitation–inhibition ratios from biophysical network models and electrophysiological markers, including aperiodic activity and gamma oscillations. As human neuroimaging proxies of neuroplasticity remain indirect, integrating across multimodal markers – together with non-human animal studies – is essential for clarifying how we can measure neuroplasticity as capacity for change and when adversity may downregulate or upregulate this capacity. Ambulatory designs can also reveal how dynamic environmental changes, such as enrichment (e.g., social support) following adversity (e.g., harsh parenting), influence neuroplasticity on a moment-to-moment timescale within individuals.

Lastly, several factors likely moderate how experience interacts with neuroplasticity. Defining adversity and parsing its heterogeneity remain active areas of inquiry that can clarify how different experiences impact neuroplasticity via distinct mechanisms. Dimensional models postulate that threat (e.g., abuse) and deprivation (e.g., neglect, restricted sensory input) may differentially shape brain and behavior, while recent frameworks consider additional dimensions of exposure (e.g., unpredictability, controllability). Furthermore, since different experiences may be most salient at different developmental stages (e.g., caregiving earlier in life, peers/neighborhoods during adolescence), the type, timing, accumulation, and recency of adversity may each interact with neuroplasticity. These processes may also depend on demographic factors. For example, biological and social processes generate sex and gender differences in the pace of neurodevelopment, degree of myelination, neuroplasticity expression, and neurobiological embedding of adversity.