“Homo sapiens, industrialisation and the environmental mismatch hypothesis”.

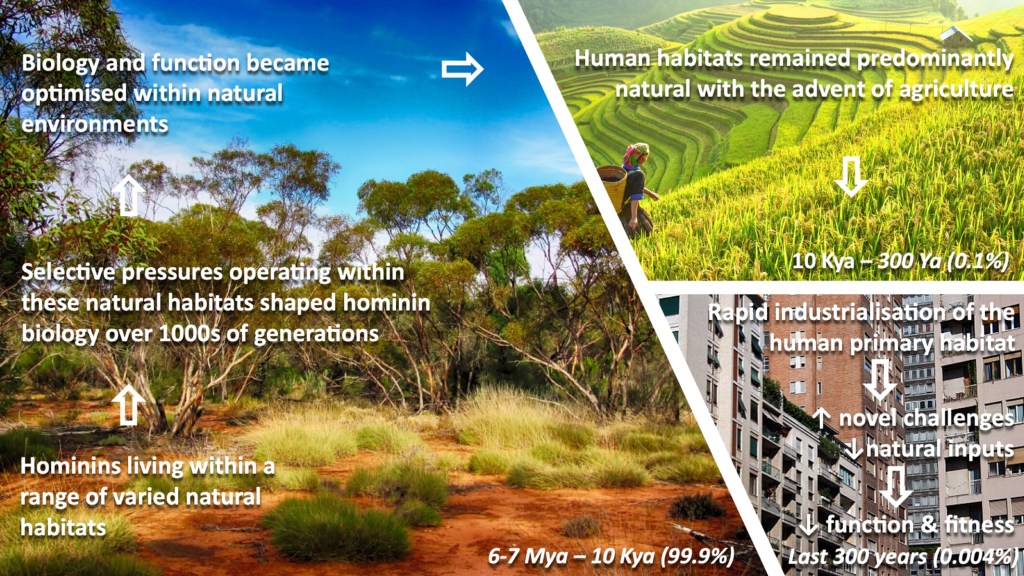

For the vast majority of the evolutionary history of Homo sapiens, a range of natural environments defined the parameters within which selection shaped human biology.

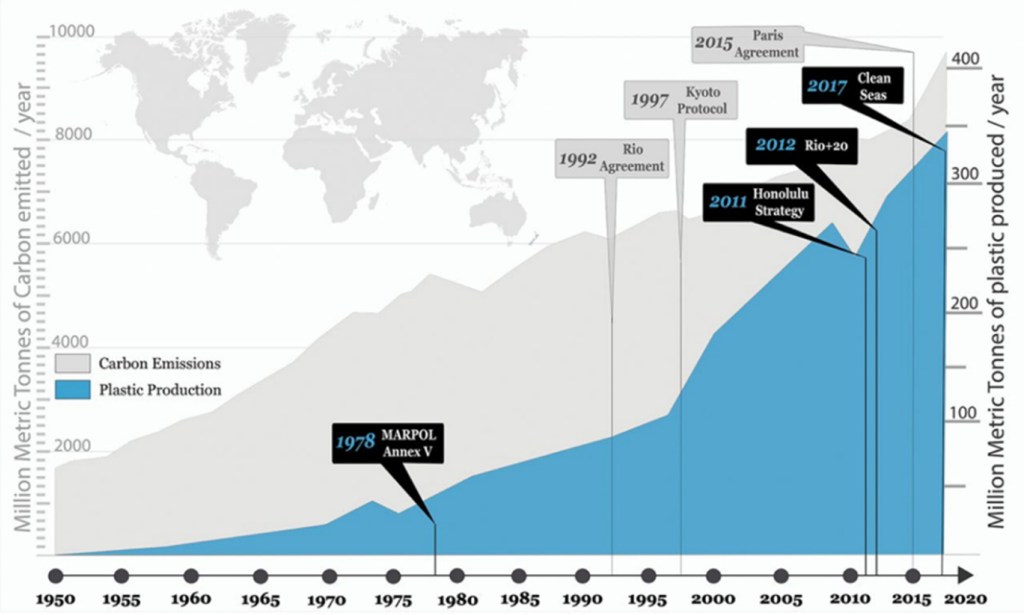

Although human-induced alterations to the terrestrial biosphere have been evident for over 10,000 years, the pace and scale of change has accelerated dramatically since the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century. Industrialisation has profoundly transformed our various natural habitats, driving rapid urban expansion, increasing reliance on fossil fuel energy and causing environmental contamination, ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss.

Today, most of the world’s population resides in highly industrialised urban areas. These new primary human habitats differ fundamentally from our ancestral natural habitats, creating novel environmental challenges while, simultaneously, lacking key natural features linked to health and function.

Although the adaptive capacity of humans has enabled survival in diverse and fluctuating environmental conditions, this capacity is limited. It is possible that the rapid industrialisation of our habitat is outpacing our adaptive capacity and is imposing selective pressures that threaten our evolutionary fitness. A growing body of observational and experimental evidence suggests that industrialisation negatively impacts key biological functions essential for survival and reproduction and, therefore, evolutionary fitness.

Specifically, environmental contamination arising directly from industrial activities (e.g. air, noise and light pollution, microplastic accumulation) is linked to impaired reproductive, immune, cognitive and physical function. Chronic activation of the stress response systems, which further impairs these biological functions, also appears more pronounced in industrialised areas.

Here, we consider whether the rapid and extensive environmental shifts of the Anthropocene have compromised the fitness of Homo sapiens. We begin by contrasting contemporary and ancestral human habitats before assessing the effects of these changes on core biological functions that underpin evolutionary fitness. We then ask whether industrialisation has created a mismatch between our primarily nature-adapted biology and the novel challenges imposed by contemporary industrialised environments – a possibility that we frame through the lens of the Environmental Mismatch Hypothesis.

Finally, we explore experimental approaches to test this hypothesis and discuss the broader implications of such a mismatch.

Industrialisation has rapidly and profoundly transformed the various natural habitats of Homo sapiens. While industrialisation has provided numerous benefits, the resulting environmental changes may be imposing selective pressures (e.g. from air pollution, microplastics, artificial noise and light) that negatively impact evolutionary fitness (the ability to survive and reproduce).

Adaptation occurs across multiple timescales to maintain homeostasis and optimise evolutionary fitness.

Immediate responses include behavioural and physiological adjustments.

Over longer periods, phenotypic and developmental plasticity enable within-lifetime adaptation.

Across generations, epigenetic inheritance modifies gene expression in response to parental environments.

If these adaptive mechanisms fail to buffer environmental stressors and preserve function, natural selection favours heritable traits that enhance survival and reproduction, leading to long-term evolutionary change.

A primary consequence of industrialisation is the release of environmental pollutants. Industrial activities like mining, construction, farming and energy production release billions of tonnes of chemically active materials annually, leading to widespread contamination. These pollutants are so pervasive that carcinogenic components are found in the blood, breast milk and tissues of all human populations, including infants and the unborn.

Air pollution, which is significantly higher in urban areas, is also associated with impaired reproductive function. Exposure to elevated levels of air pollutants negatively affects both male and female gametogenesis and increases the risk of spontaneous pregnancy loss. Between 1973 and 2018, rising air pollution was associated with a 51.6% decline in global sperm concentration and a 62.3% decrease in total sperm count. A recent meta-analysis further supports this link, associating air pollution with decreased sperm concentration, total sperm number and mobility.

In rural areas, industrial pesticides and herbicides impair reproductive function. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 studies, for example, found a clear relationship between exposure to both organophosphate and N-methyl carbamate insecticides and reduced sperm concentration. Similarly, a recent systematic review found glyphosate-based herbicides – the world’s most widely used pesticides – were linked to lower testosterone, impaired sperm count and mobility, preterm birth (reported in two of three human studies), and birth defects (found in four of five studies, including two involving humans).

In parallel, unprecedented production of plastic products has led to widespread environmental contamination by micro- and nanoplastics – plastic fragments smaller than 5 mm and 1 μm, respectively – generated from the breakdown of objects such as tyres and clothes and which are directly manufactured for use in cosmetics. Their small size and persistence allows them to accumulate in body tissues via ingestion, inhalation and cutaneous absorption. Micro- and nanoplastics impair male fertility by decreasing sperm quality via inflammation and oxidative stress and disrupt female fertility by altering metabolism, inducing oxidative stress, damaging DNA and modulating the epigenome, and inducing developmental abnormalities in offspring. A recent review called for larger observational studies to evaluate the direct impact of micro-plastics on human reproductive function.

Chemicals leaching from industrial and consumer products also compromise reproductive function. Flame-retardant chemicals such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers can permanently impair male reproductive function. Similarly, phthalates – ubiquitous plasticisers found in consumer products – disrupt endocrine function, interfere with nuclear and membrane receptors, intracellular signalling pathways and gene expression associated with reproductive function and cause fertility disorders in both men and women.

In summary, worldwide fertility rates are declining, partly due to the impairment of reproductive function caused by industrial pollution. Air pollution, more pronounced in urban settings, disrupts gametogenesis, reduces sperm quality and increases risk of pregnancy loss. In rural areas, pesticide and herbicide exposure lowers sperm quality and testosterone while increasing risks of birth defects and preterm birth. Micro- and nanoplastics accumulate in body tissues, decreasing sperm quality in men and impairing reproductive function in women. Additionally, chemicals such as phthalates and flame retardants disrupt the endocrine system, further interfering with reproductive pathways and leading to fertility disorders.

Future investigation into whether industrialisation has created a human-induced environmental mismatch would benefit from following three key principles.

First, research should comprehensively assess the impact of industrialised environments on key functions that underpin evolutionary fitness, relative to natural environments representative of ancestral habitats. Such an approach would reconcile the current scarcity of high-quality, reproducible studies that consider how industrialisation affects function and evolutionary fitness.

Second, studies should be designed to prolong exposure (lasting days rather than minutes) to both natural and industrial environments, allowing more time for environmental features to influence human biology. This would provide deeper insights into the cumulative effects of highly industrialised and natural environments and clarify how adaptive processes in ancestral environments have shaped human phenotypes. Regular assessment of biological function throughout exposure would further elucidate dose–response relationships.

Third, research should explore the mechanisms by which industrialisation influences biological function. This can be achieved through a combination of field and laboratory experiments designed to identify specific aspects of industrialised environments that impair human function and features of ancestral natural habitats that may be absent from contemporary industrialised settings and are essential for optimal function.

CONCLUSIONS

- (1) For the vast majority of the evolutionary journey of Homo sapiens, a range of natural environments defined the parameters within which selection shaped human biology.

- (2) The rapid environmental changes of the Anthropocene, driven by industrialisation, have profoundly transformed the human habitat, imposing novel environmental pressures.

- (3) The rate of environmental change may be outpacing human adaptive capacity, potentially compromising our evolutionary fitness.

- (4) A growing body of empirical evidence suggests that environmental industrialisation negatively impacts human biology, suppressing key biological functions essential for survival, reproduction and, therefore, evolutionary fitness.

- (5) We consider whether industrialisation has created a mismatch between our primarily nature-adapted biology and the novel challenges imposed by contemporary industrialised environments, a possibility framed through the Environmental Mismatch Hypothesis.

- (6) This mismatch could have broad interdisciplinary relevance, from advancing understanding of adaptational processes in prehistoric and 21st century humans to addressing contemporary public health challenges and issues of global sustainability.