Creative ideas emerge from the process of searching and combining concepts in memory, involving both associative and controlled mechanisms.

How these processes unfold during memory search and relate to creativity remains unclear.

We explored the neurocognitive underpinnings of semantic memory search using a clustering–switching framework and the Marginal Value Theorem (MVT) from optimal foraging theory.

During an associative fluency task with polysemous words, most responses aligned with MVT predictions, but some deviated from them. These behavioral results were replicated in an independent sample. Connectome-based modeling revealed that functional brain connectivity predicted these MVT-deviant patterns and mediated the relationship between brain connectivity and creative performance. These findings suggest that the cognitive policy favoring creativity may differ from the policy optimizing fluency (i.e., MVT).

This study introduces novel measures of semantic search, identifies their neurocognitive correlates, and underscores the importance of search patterns in understanding creative abilities.

Alternative uses task (AUT)

In the AUT, participants were instructed to generate as many alternative uses as possible for three common objects: tire, bottle, and knife. The experimenter presented the instructions orally, and then participants read them on the computer screen before starting the task. After reading the instructions, the object’s name was displayed on the computer screen and remained until the time ran out. Participants were given 3 minutes for each object to write all their responses on the computer using a keyboard. At the end of the 3 minutes, participants were asked to select their two most creative ideas for each object (top-2). We computed three scores for each object: AUT_fluency, AUT_uniqueness, and AUT_ratings.

The combination of associates task (CAT)

The CAT is an adaptation of the classical creativity task named the Remote Associates Test. In the CAT, participants were presented with 100 trials composed of triplets of cue words that, at first glance, seem unrelated. For each trial, participants were asked to find a fourth word (i.e., the word solution) that relates to all the cue words within 30 seconds. In this version of the task, the trials vary on the semantic distance between the cue words and the solution, being composed by 50 close trials (low semantic distance between the cue words and the response) and 50 distant trials (high semantic distance between the cue words and the response). At the end of each trial, participants were asked to report whether the solution was found with a feeling of insight or Eureka, that is, when the solution comes to mind suddenly and effortlessly. We computed three scores: CAT_CR, CAT_index, and CAT_eureka

Executive function tests

We assessed executive functions with three classical neuropsychological tests: digit span (working memory, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – WAIS), trail-making (set-shifting), and Stroop (inhibition).

Polysemous Fluency Task (PolyFT)

Using polysemous words as cues to characterize behavioral components of clustering and switching. Findings indicated that clustering and switching components both relate to individual differences in creative abilities but reflect distinct neurocognitive processes. Specifically, the clustering component was linked to greater fluency and originality in a divergent thinking task and involved higher brain functional connectivity between executive control and attentional networks.

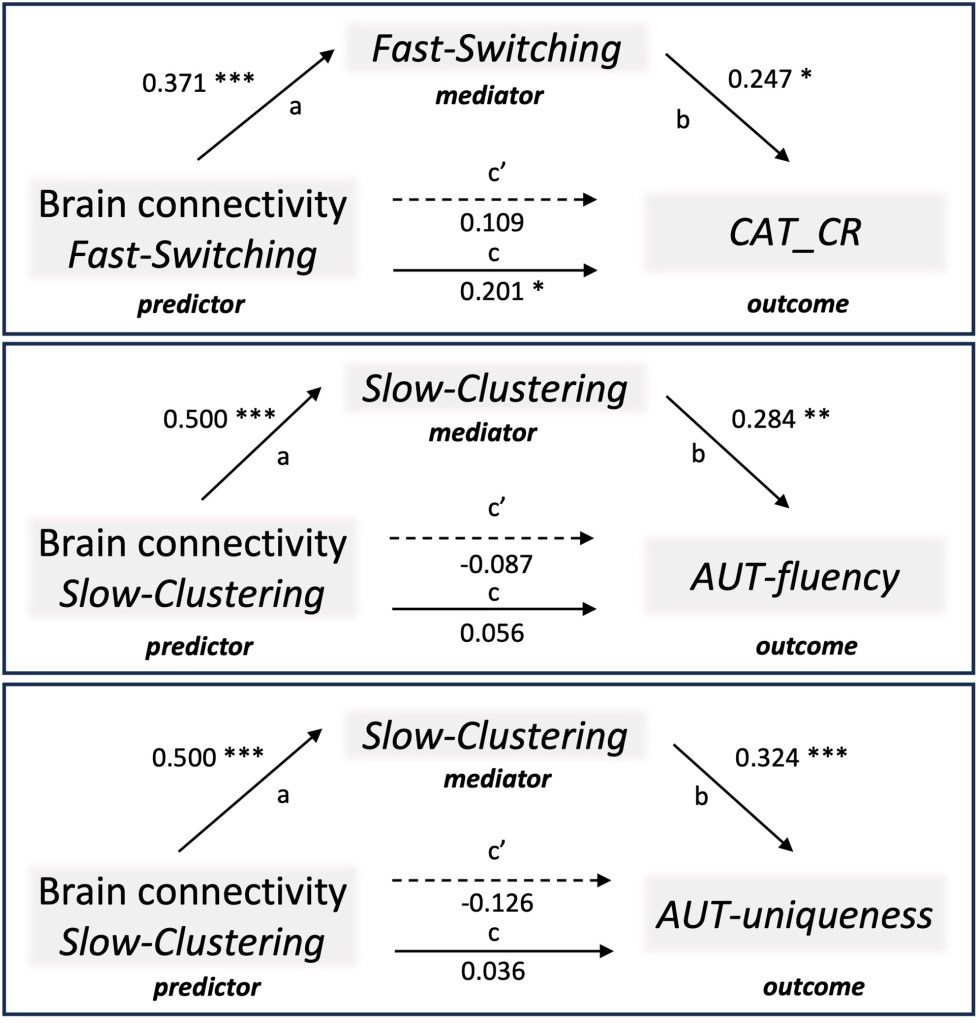

We examined the mediating role of Fast-Switching on the relationship between the brain connectivity patterns predicting it (predictor) and CAT_CR.

The regression coefficients between the brain connectivity pattern and Fast-Switching (b = .371, p < .001) and between Fast-Switching and CAT_CR (b = .247, p < .05) were significant. The total effect (c path) represented by the regression coefficient between the brain connectivity patterns and CAT_CR was significant (b = .201, p < .05), and the direct effect (c’ path) was not significant (b = .109, p = .294). The indirect effect was significant (0.371 × 0.247 = .092), with a 95% bootstrapped confidence interval [0.019, 0.206].

Hence, Fast-Switching mediated the relationship between the positive predictive network model of Fast-Switching and CAT performance: The higher the strength of connectivity in the positive network model that predicts Fast-Switching, the higher the number of Fast switches in semantic retrieval, and the higher the abilities to combine remote associates in memory.

We also explored the mediation analyses for Slow-Clustering. Because Slow-Clustering correlated only with the fluency and originality of the participants in the AUT, we explored the mediating role of Slow-Clustering on the relationship between the brain connectivity patterns predicting it (predictor) and AUT_fluency and AUT_uniqueness in independent analyses.

As shown in the previous analyses, the regression coefficient between the brain connectivity pattern and Slow-Clustering (b = .50, p < .001) was significant. The regression coefficients between Slow-Clustering and AUT_fluency (b = .284, p < .01) and between Slow-Clustering and AUT_uniqueness (b = .324, p < .001) were significant.

The total effect (c path) and the direct effect (c’ path) between the brain connectivity patterns were not significant for AUT_fluency (total effect: b = .056, p = .549; direct effect: b = -.087, p = .390) or for AUT_ uniqueness (total effect: b = .036, p = .691; direct effect: b = -.126, p = .200). For AUT_fluency, the indirect effect was significant (0.50 × 0.284 = .142, with a 95% bootstrapped confidence interval [0.06, 0.29]), while for AUT_originality, the indirect effect was significant (0.50 × 0.324 = .162), with a 95% bootstrapped confidence interval [0.072, 0.32].

Hence, Slow-Clustering mediated the relationship between the positive predictive network model of Slow-Clustering and AUT performance: The higher the strength of connectivity in the positive network model that predicts Slow-Clustering, the higher the frequency of slow clustering responses during semantic retrieval, and the more participants were fluent and original in the divergent thinking task.

The results of the mediation models are presented in path diagrams. Each diagram indicates the beta weights of the regression coefficients, with the brain connectivity pattern of the model network (brain connectivity predictive of Fast-Switching and Slow-Clustering) as the independent variable (predictor), PolyFT responses (Fast-Switching and Slow-Clustering) as the mediator, and creative abilities to combine remote associates (CAT_CR) and divergent thinking (AUT-fluency and AUT-uniqueness) as the dependent variable (outcome).

The total effect of the predictor on the outcome is indicated by path c, the direct effect by path c′, and the indirect effect is given by the product of path a and path b. The indirect effect was significant in all the reported mediations. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Processes occurring during searching in memory are critical for creativity but remain to be clarified. This study characterized distinct foraging behaviors during semantic search and retrieval, explored their brain correlates, and their relationships with creative abilities and executive function abilities. Converging results from two datasets confirmed our core hypothesis: during PolyFT, individuals generally follow an optimal foraging policy consistent with the MVT. However, not all responses adhered to this policy, with some switches occurring faster and some clustering responses occurring slower than MVT predictions. The identification of such patterns provides new hypotheses and measures for investigating the processes involved in semantic foraging.

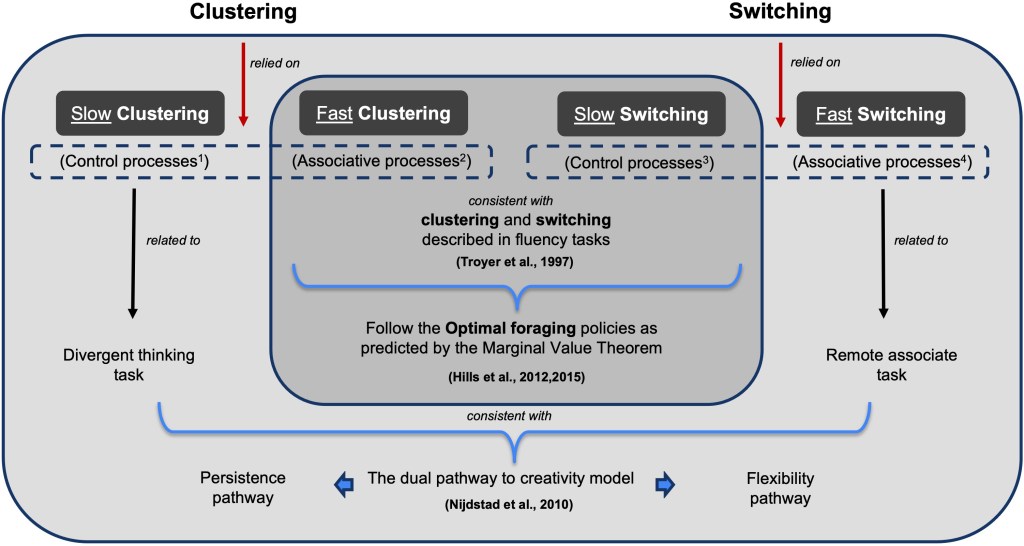

The differentiation between these fast and slow responses allows for reconciling prior theories and approaches, as these response types likely reflect distinct underlying cognitive processes or strategies. Specifically, fast clustering and slow switching are consistent with MVT principles and with the classical distinction of clustering and switching in fluency tasks. In contrast, fast switching and slow clustering are relevant to creativity and may align with the flexibility and persistence pathways of the “two pathways to creativity” model. We further identified functional connectivity patterns predictive of the frequency of fast switching and slow clustering responses, revealing that fast switching between clusters (which might be related to spontaneous processes) mediates the relationship between brain connectivity and the ability to combine remote associates in memory, whereas slow clustering (which might be related to controlled processes) mediates the relationship between brain connectivity and divergent thinking abilities.

This figure illustrates our interpretations of slow clustering, fast clustering, slow switching, and fast switching responses based on our findings at both the behavioral and brain levels.

The red arrows indicate that both clustering and switching responses rely on associative and control processes.

Light gray: slow clustering involves control processes and is related to divergent thinking tasks. Fast switching involves associative processes and is related to the remote associate task. These patterns are consistent with the dual pathway to creativity model, linking slow clustering and fast switching to the persistence and flexibility pathways, respectively.

Dark gray: fast clustering involves associative processes, while slow switching involves control processes. These patterns align with clustering and switching described in classical fluency tasks and follow the optimal foraging policies as predicted by the MVT.

Note: 1suggested by brain predictive patterns but not correlated with executive control tasks; 2hypothesized but not tested; 3correlation with TMT-shifting; 4suggested only by brain predictive patterns.

Overall, the current study clarifies and extends previous findings linking classical clustering and switching to semantic memory structure, executive control, and creative abilities. By analyzing the data using a different approach, in light of the MVT, we were able to advance our understanding of memory search processes in creative abilities. Here, we identify two distinct search patterns. One pattern, characterized by fast clustering and slow switching responses, is consistent with the MVT policies and with the classical interpretations of the processes underlying clustering and switching responses during searching in memory. Fast clustering likely involves associative processes, while slow switching relates to controlled processes. Consistent with our first and second hypotheses, these MVT-consistent patterns were associated with greater fluency, suggesting they reflect efficient retrieval processes during the PolyFT.

However, we introduce a second pattern including slow clustering and fast switching responses that is not following the MVT policy but relates to creative abilities and mediates the relationship between brain connectivity and creative abilities, confirming our third and fourth hypotheses. Theoretically, slow clustering and fast switching responses deviate from MVT policy but may align with the dual pathway to creativity model, which proposes persistence and flexibility as distinct paths for creative idea generation. In this model, persistence refers to an effortful, sustained search involving cognitive control, while flexibility refers to generating ideas by shifting between categories or perspectives, potentially involving automatic or controlled processes, depending on task demands and individual differences. We propose that slow clustering captures a persistent local semantic search to maximally exploit a cluster, requiring cognitive control, reflected in the involvement of the executive control and attentional networks, and is critical for divergent thinking. Conversely, fast switching reflects an associative form of flexible search across various semantic clusters, which seems to involve the default mode network, and relates to the ability to combine remote concepts (as measured by the CAT).

These findings are consistent with recent evidence showing that retrieval flexibility mediates the link between brain dynamics and creativity. Taken together, these findings refine existing models by suggesting that creativity can emerge not only from the interaction between default mode network and frontoparietal control network but also from the flexible recruitment of distinct network configurations depending on the type of cognitive search strategy.

Importantly, while MVT-consistent patterns (i.e., fast clustering and slow switching) maximize fluency in the PolyFT, MVT-deviant patterns (i.e., slow clustering and fast switching) may reflect persistence and flexibility during search that facilitate creativity, as we showed a link between these MVT-deviant patterns and greater originality of the responses in the PolyFT. Notably, participants were not instructed to be creative; yet our mediation and correlation findings showed that those with more fast switching or slow clustering responses had higher creative performance on independent creativity tasks (i.e., CAT and AUT). These results support the idea that cognitive policies fostering creativity may diverge from those optimizing fluency and highlight the importance of both persistence and flexibility in creative abilities.

Our findings demonstrate that the processes occurring during memory search differ between individuals and relate to creativity.

By characterizing fast and slow clustering and switching, we captured more nuanced aspects of semantic foraging behavior during the PolyFT, separating behavioral responses that reflect optimal foraging from those that represent creativity‐relevant deviations.

Patterns consistent with foraging principles (fast clustering and slow switching) supported efficient retrieval and fluency, while deviations from this policy (slow clustering and fast switching) mediated the link between brain connectivity and creative performance.

Slow clustering is interpreted as a persistent search supported by attentional and control networks and related to divergent thinking, whereas fast switching reflected a flexible search supported by default mode connectivity and related to combining remote associations.

Altogether, these findings help clarify the discrepancies between previous approaches and theories on memory search by extending classical foraging models, showing that deviations from purely optimal retrieval can be helpful for creativity and providing a framework for linking semantic search dynamics, creative thinking, and brain network organization.

Moreover, our findings introduce new measures of memory search behavior that can help advance our understanding of the cognitive processes underlying creativity in future studies.