Delusions in psychosis involve complex and dynamic experiential, affective, cognitive, behavioural, and interpersonal alterations.

Their pattern of emergence during the early stages of illness remains poorly understood and the origin of their thematic content unclear.

Phenomenological accounts have emphasised alterations of selfhood and reality experience in delusion formation but have not considered the role of life events and other contextual factors in the development of these disturbances.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between self-experience and the lived world in first-episode psychosis by situating the phenomenological analysis of delusions in the context of the person’s life narrative.

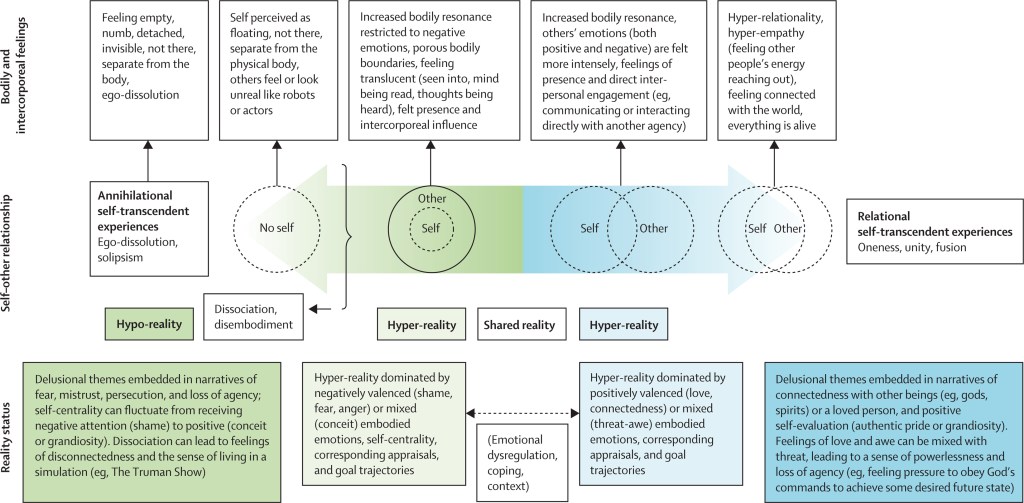

On the left (green) is the global transformation (driven by shame) of the lived world into a hostile and rejecting social world, and the lived body into a vulnerable and translucent medium that does not have privacy over the intrusion of the omnipresent gaze of the other. On the right (blue) is the predominantly positive transformation of the world driven by awe, love, and hope.

In our study, some participants described dynamic, sometimes rapid, shifts between different emotions and world experiences, moving back and forth across the spectrum. These fluctuations were characterised by varying degrees of emotional instability shaped by factors such as coping strategies (eg, avoidance vs immersion or absorption), substance use, not getting enough sleep, and the affective character of the social and material environment. Because feelings of threat could be had both in relation to shame and awe (as in threat-awe), persecutory ideas were present at either side, but the representation of the self was negative on the left (eg, perceive themselves to be a “paedophile”, “monster”, or “bad person”) and positive on the right (eg, a spiritual person, the “chosen one”, or connected to God.). At the extreme ends are high-intensity self-transcendent experiences, which were described as positive (eg, similarly to peak and mystical experiences) when immersed in positive emotions, or negative when resulting from disembodiment in the context of predominantly negative embodied emotions (such as shame, fear, anger, and hubristic pride).

The research shows that unpacking the complexities of delusions requires rejecting their conceptualisation as purely cognitive, mental, or disembodied phenomena that are separate from perception, action, or affect and recognition of their embodied and intercorporeal character. Addressing the subjectivity of delusions and their rootedness in affective consciousness and in embodied processes of emotional regulation and intercorporeal attunement is key for advancing our understanding and treatment of delusions.