“Boredom and curiosity: the hunger and the appetite for information“

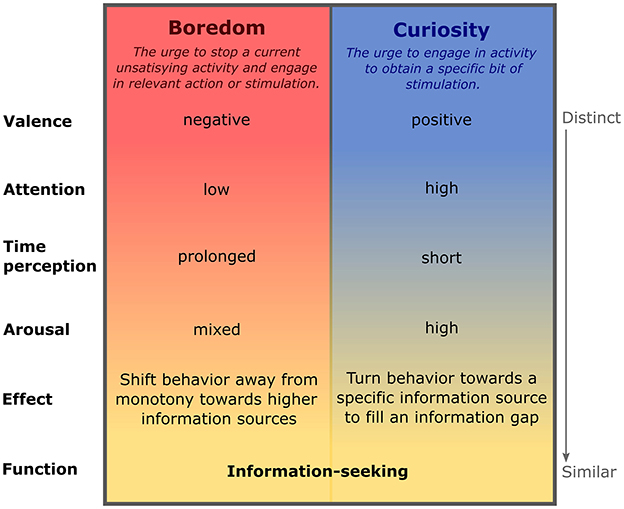

Boredom and curiosity are common everyday states that drive individuals to seek information. Due to their functional relatedness, it is not trivial to distinguish whether an action, for instance in the context of a behavioral experiment, is driven by boredom or curiosity.

Are the two constructs opposite poles of the same cognitive mechanism, or distinct states? How do they interact? Can they co-exist and complement each other? Here, we systematically review similarities and dissimilarities of boredom and curiosity with respect to their subjective experience, functional role, and neurocognitive implementation.

We highlight the usefulness of Information Theory for formalizing information-seeking in the context of both states and provide guidelines for their experimental investigation. Our emerging view is that despite their distinction on an experiential level, boredom and curiosity are closely related on a functional level, providing complementary drives on information-seeking: boredom, similar to hunger, arises from a lack of information and drives individuals to avoid contexts with low information yield, whereas curiosity constitutes a mechanism similar to appetite, pulling individuals toward specific sources of information.

We discuss predictions arising from this perspective, concluding that boredom and curiosity are independent, but coalesce to optimize behavior in environments providing varying levels of information.

Boredom and curiosity appear most commonly as transient mental states in response to particular environmental or internal conditions of an individual.

We describe curiosity and boredom as two independent cognitive states, that converge on a functional level. Surprisingly, despite their functional relatedness, both constructs have mostly been studied in isolation, leading to a fragmented understanding of their interplay. Can both states co-occur, or are they mutually exclusive?

In contrast to their nature as a state, boredom and curiosity on a trait level can co-exist and even influence each other. In this context, it was found in self-report-based studies that trait boredom and trait curiosity can exhibit a negative correlation as well as a positive correlation, reflected by correlation coefficients in the range of ~-0.3 and +0.5. This opens the possibility for individuals to profit from both, either boredom or curiosity that can both be potentially elicited, depending on the current situational condition. While a highly boredom-prone subject in a given environment, offering average degrees of stimulation, might be overall more likely to experience boredom, the evoked state of boredom can transition into curiosity in the next moment, for instance when changing the environment. Over longer time scales, both states might hence alternate and, even if they do not co-exist at the same time, affect and complement each other over consecutive points in time. In line with this perspective, it was shown that the trait of being open to novel experiences is a strong positive predictor of trait curiosity, but correlates negatively with boredom proneness. In the same study, personality traits were identified as significant factors mediating the relationship between boredom and curiosity. Thus, trait boredom and trait curiosity together with other personality features may set a foundation for individual cognitive response tendencies, while at the same time allowing individuals to fall into different states based on the conditions of the current situation, thus flexibly switching between curiosity and boredom.

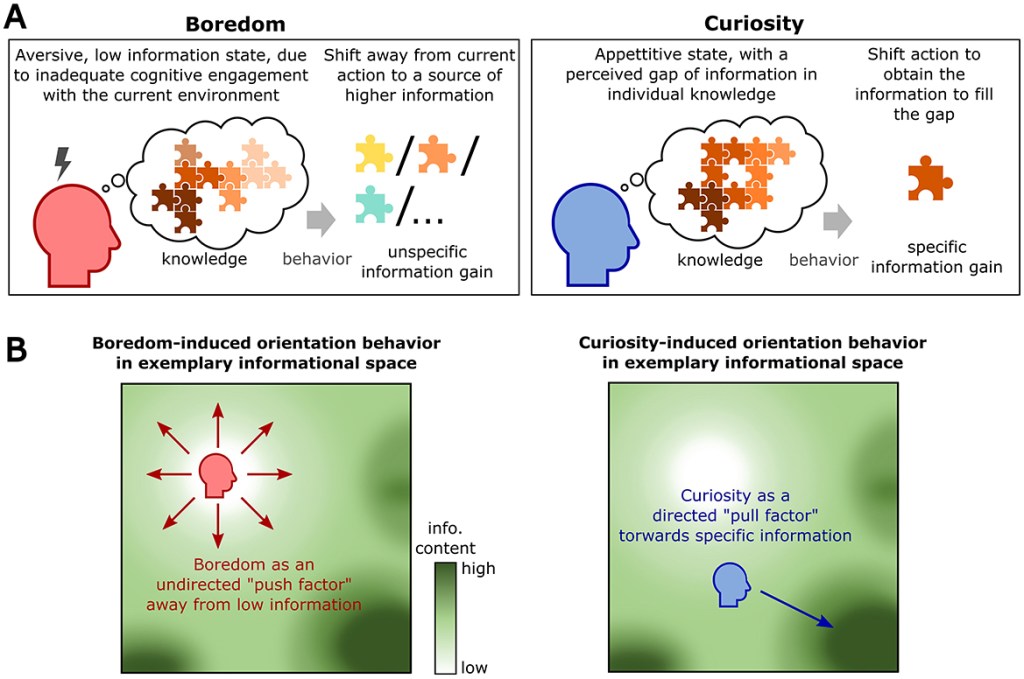

Boredom and curiosity both constitute central drivers of information-seeking that arise in different contexts, with distinct pull-push dynamics. In this section, we detail information-oriented perspectives on both phenomena: boredom, on the one hand, pushing individuals away from monotonous information sources, and curiosity pulling individuals toward specific information sources, aimed at filling information gaps. These distinctions affect downstream information-seeking behavior, determining the type of information sought and, as a result the individual’s overall knowledge.

Information, the abundance or scarcity of it, is a key concept in the emergence of curiosity and boredom.

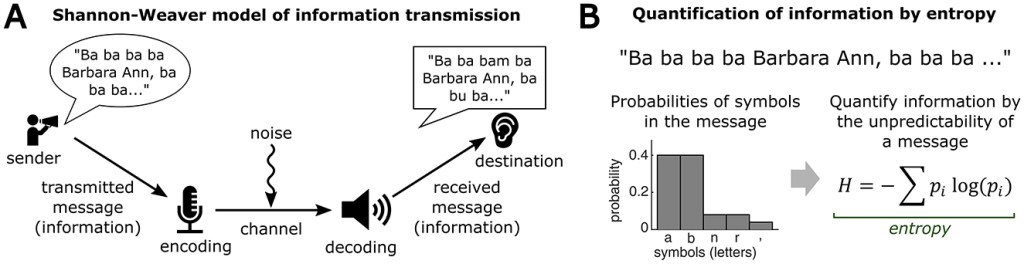

(A) A standard model of information transmission. A message is encoded into a sequence of symbols, and sent out through a communication channel, before becoming decoded and interpreted by a receiver. Thus, effectively transmitted information always depends on the interplay and coherence between sender and receiver.

(B) Information Theory allows a quantification of the information content of a message as entropy, based on the probability distribution of symbols in the message.

The Information Theory framework and the quantitative characterization of an environment’s entropy can be broadly applicable to experimental designs, where transmitted information may be conceived as originating from a source (e.g., an environmental auditory stimulus), passing through a channel of a sensory organ (e.g., cochlea) and being decoded by the brain into an updated perception.

An important note on quantifying informational entropy relates to the decision on the level of describing a stimulus, for example, the phonetic vs. semantic content of a spoken message. Here, an individual’s capability to effectively decode information from the sensory variability in a message is crucial. In particular, the internal personality features and cognitive abilities of an individual may determine its ability to effectively process sensory stimuli, thus affecting how much information is drawn from a sensory message.

Hence, effective information transmission depends on two factors, (i) the amount of objective variability in a sent message, and (ii) the subjective ability of a receiving agent to process the sensory variability and decode the message.

This information-theoretic perspective aligns well with the idea that the brain aims to optimally allocate its mental resources to environmental stimulus sources, in order to maximize its cognitive engagement: A mismatch of the objective information content provided by the current sensory environment and the internal decoding abilities of an agent would lead to low information transmission, reflected by low cognitive engagement. In contrast, a match of the objective information content in the current environment and the internal decoding abilities of an agent would lead to high information transmission, reflected by strong cognitive engagement. Thus, efficient allocation of mental resources to adequate environmental stimuli may drive cognitive engagement by ensuring a continuous, effective transmission of sensory information to the brain.

(A) Boredom and curiosity differently affect information-seeking. Left: Boredom arises in states of low information transmission, largely independent from prior knowledge, and unspecifically shifts behavior toward other sources of information in the environment. Right: Curiosity arises from specific gaps in the knowledge of an individual, largely independent from current information transmission, and drives behavior to fill these knowledge gaps by acquiring specific pieces of information.

(B) Illustration of action trajectories of bored and curious agents in an exemplary environment that offers sources with varying information content. Left: Boredom would push individuals away from sources of monotony (low information) to unspecifically explore sources of higher information. Right: In contrast, curiosity would pull individuals to exploit specific sources of information that fill internal information gaps.

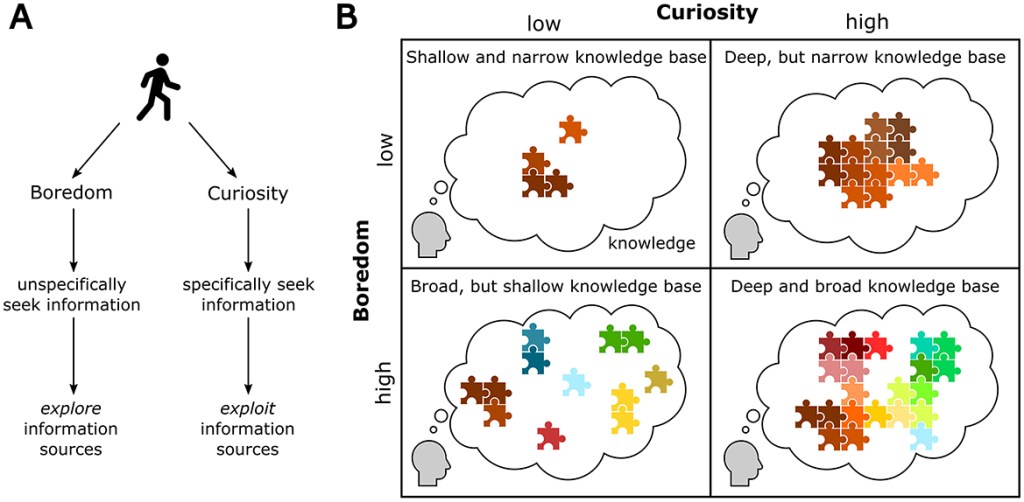

Complementing effects on exploration and exploitation behavior

The above characterization of boredom and curiosity as two independent cognitive signals that drive the search for unspecific vs. specific information, highlight both phenomena as functionally complementary cognitive mechanisms. Specifically, while boredom emerges under selective conditions where an individual’s current environment only provides scarce information, curiosity can emerge independently from the current environment, evoked merely by raised information gaps in internal knowledge. Moreover, boredom pushes individuals away from the current action to find higher information, whereas curiosity attracts individuals to specific sources of information. Hence, the functions of boredom and curiosity can be compared to other cognitive signals such as hunger and appetite that serve complementing purposes: Similar to hunger, which can be satisfied with basically any food, boredom drives individuals to engage in almost any action that leads to enhanced information. Importantly, in this condition subjects do not need any a-priori estimate of the quality of this achieved information, making boredom a central driver to explore novel actions and environments. In contrast, the function of curiosity can be well compared to appetite, directing individual behavior toward specific sources of stimulation that can integrate into specific knowledge gaps). Curiosity by definition requires a vague estimate of the desired information, defined by the individual knowledge network associated to the information gap. This in consequence promotes an exploitation of stimulation sources from which an individual would expect to receive the specific, desired bits of information. Thus, boredom acts as a safeguard mechanism to prevent individuals from stagnancy in uninformative, meaningless environments, whereas curiosity attracts individuals to develop their knowledge about the world and increase their behavioral fitness, appearing in basically any environment. Both features together can serve to balance out exploitation-exploration strategies, overcome local minima of information in an environment and hence optimize long-term reward.

(A) Given the distinct effects on information-seeking, boredom essentially drives unspecific exploration behavior, whereas curiosity drives specific exploitation of information sources.

(B) This predicts different knowledge structures of agents characterized by varying extent of boredom and curiosity respectively. Agents with low boredom and low curiosity would only have narrow and scarcely developed knowledge base. High boredom and low curiosity would lead to a widely spread knowledge network that however shows only low density and hence leaves many gaps. High curiosity and low boredom would lead to a dense knowledge base with only few information gaps, however with only little extent on different topics. High boredom and high curiosity combined would lead to a multidimensional and densely connected knowledge network.

oredom and curiosity constitute highly relevant cognitive states, ubiquitously experienced across life. While both phenomena are characterized by distinct and widely opposing experience, they functionally cooperate to drive information-seeking. Boredom, characterized by negative affect, low attention and prolonged time perception, typically arises in situations of low sensory information transmission to an individual and drives individuals to behaviorally search for any source of higher information. Curiosity, defined by positive affect, enhanced attention and shortened time perception, arises from defined internal knowledge deficits, driving individuals to seek for specific information to fill these deficits. Hence boredom and curiosity form a functional unit, complementing each other: Similar to hunger, boredom pushes individuals to unspecifically explore, whereas curiosity, similar to appetite, pulls individuals to exploit specific information sources. These cooperative effects on different dimensions of information-seeking guide individuals to flexibly adjust their behavior in environments with varying and dynamic sources of sensory information. Considering this interplay can in the future help to delineate boredom- and curiosity-related effects in empirical studies, and hence yield a deeper understanding of how both phenomena are rooted in the brain and how they affect cognition.