A great review article describes the bottom-up and top-down processing from Marr’s computational-algorithmic-implementation perspective to understand depressive and anxious disease states. The review illustrate examples of bottom-up processing as basolateral amygdala signaling and projections and top-down processing as medial prefrontal cortex internal signaling and projections. Understanding these internal processing dynamics can help us better model the multifaceted elements of anxiety and depression.

The brain is a dynamic system that depends on multiple hidden variables, of which we can only observe a minority. The ongoing activity of a single cell is governed by the combination of inputs: their amplitude, location, timing, and regulation of ion channels combined with slower signals from neuromodulation. On a larger scale, a cell receives inputs from tens of thousands of other neurons, whose connections and activity are unknown. Such a vast number of hidden variables in neural activity demand computational models that can represent biological activity accurately—understanding the brain as a dynamic system accounts for these hidden variables that cannot be observed. Such models contain “attractor states,” which represent states that a system gravitates toward regardless of initial conditions. As Antonio Damasio argues in his work, The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness, motivational senses of self emanate from a proto-self—a collection of patterns that summate and map the momentary homeostatic needs of an individual in many dimensions.

Mounting evidence suggests that neural ensembles demonstrate activity that is similar to attractor state models. An attractor network (distinct from the attractor state) is a type of dynamic network that evolves toward stability over time.

Patients with diagnosed anxiety and depression reveal different brain states as represented by functional MRI (fMRI) readouts, suggesting that anxiety and depression exist in separate attractor states. Human imaging studies indicate a significant relationship between anxious arousal and increased amygdalar–subcortical activity. In humans experiencing anhedonia, researchers observe increased limbic–paralimbic activity. Interestingly, areas with increased activity in anxiety had decreased activity in patients with depression and areas with decreased activity in anxiety had increased activity in patients with depression. The existence of these separate brain states supports the theory that there are bistable attractor states that can represent anxiety and depression (Figure 1A–E). As individuals exhibit an increased tendency toward TD or BU processing, attractor states reflect a similar geometry—the depth of one attractor state represents the increased likelihood that network activity will gravitate toward that type of processing. As we illustrate in Figure 1, healthy individuals can smoothly alternate between TD and BU processing states to modulate behavior appropriately.

In pathologic conditions, the depth of the attractor states increases such that network activity is heavily biased toward either TD (in depression) or BU (in anxiety) (Figure 1B,C).

Bottom-up (orange) and top-down (blue) processing in

(A) healthy, (B) anxious, (C) depressed, (D) slow-switching comorbid, and (E) fast-switching comorbid states are represented through attractor state dynamics (upper), where the ball indicates population activity at a given state with arrows showing average range of motion, and through the transition probability between states (lower), where the thicker arrows indicate higher transition probabilities.

(F) Disordered transition probabilities result in different phenotype presentations. When the transition probability between TD/BU states is critically low, patients present anxiety, depression, or slow-switching comorbidity. When the transition probability between TD/BU states is critically high, patients present fast-switching comorbidity.

(G, upper) Attractor state depth can change from Hebbian (purple) and homeostatic (green) plasticity changes.

(G, lower) Plasticity changes are altered on different timescales; whereas Hebbian plasticity deviates from the basal setpoint, homeostatic plasticity resolves plastic deviations and, if needed, re-establishes the basal setpoint.

Abbreviations: AMPAR, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic receptor; BU, bottom-up; TD, top-down.

Changes in the geometry of an attractor state may represent neural dynamic changes in firing rate or synaptic strength. Increased depth of attractor states has been biologically described by excitatory glutamatergic ion receptor function and spine concentration (Figure 1G). Changes in the geometry of an attractor state may represent neural dynamic changes in firing rate or synaptic strength.

Increased depth of attractor states has been biologically described by excitatory glutamatergic ion receptor function and spine concentration. In the context of attractor networks, plasticity is the way that attractor states can change and stabilize their geometry. While the depth of attractor states is dependent on plasticity, changes in plasticity probability can be induced through long-term enhancement or depression of excitability via homeostatic plasticity.

STIMULUS PROCESSING INVOLVES A BALANCE OF TOP-DOWN AND BOTTOM-UP

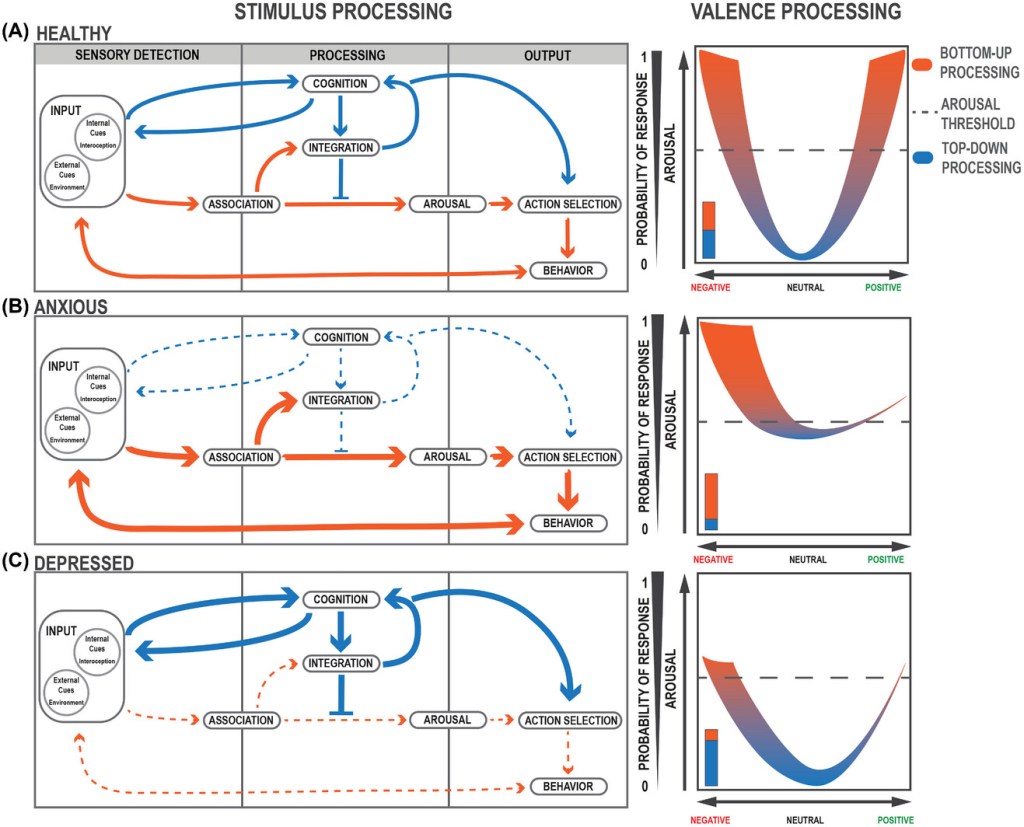

Changes in attractor state dynamics can result in major shifts in how stimuli are processed. At the algorithmic level, we distinguish between two feedback loops that, when balanced, allow for appropriate assessment and response to stimuli. The rapid and unidirectional BU feedback loop allows for immediate responses to sensory stimuli, whereas the slow and convoluted TD feedback loop allows for more complex assessments of the environment and fine-tuned behavior. These loops proceed in three main steps: sensory detection, processing, and output (Figure 2A).

Sensory detection

The first task of the system is to appropriately identify relevant information from an overwhelmingly stimulus-filled environment. Input signals, composed of both external (e.g., sounds from the environment) and internal cues (e.g., hunger), are detected by sensory processes in the body in a preattentive, automatic phase. Here, the brain must determine what is salient enough to bring to the forefront of attention and potentially act upon. For instance, studies have indicated that individuals have a latency bias toward identifying fearful stimuli among a background of nonfearful stimuli when compared to the reverse.

Salient stimuli will meet an attention threshold at the first BU node: association (Figure 2A). Associative processes, both learned and innate, allow for valence assignment of the stimulus as positive (appetitive or rewarding), negative (threatening or aversive), or neutral.

At the same time, input cues are sent to the central node of the TD loop: cognition, involved in conscious, goal-directed thinking.

Processing

Integration receives inputs from both BU and TD centers to contextualize and assess relevant information about the stimulus. The BU loop allows for information concerning the valence and intensity of the stimulus to be transmitted directly to the arousal node to bring the body into a state of psychological and physiological alertness. The TD loop may counteract these efforts by filtering out stimuli that are irrelevant or unnecessary for goal-oriented behavior. This allows for disengagement from the stimulus to prevent an inappropriate response. The TD loop continuously incorporates new information from changing environments and involves multiple iterative, inner feedback loops to continue amending cognitive assessments of stimuli. A loud barking sound, for example, might initially prompt a startle response, triggered by BU processing, but as more relevant information surrounding this sound is integrated by TD processes, one would notice the dog is safely held by an owner on the leash.

Output and feedback

Action selection is again informed by a balanced interplay of both loops: arousal and cognition. Once the action has been selected, a behavioral response is produced, to move toward or away from an external stimulus (e.g., moving away from a spider) or to change an internal state (e.g., eating food). Action selection feeds back into the cognitive node allowing for future strategization and goal orientation. These actions reconfigure the set of stimuli presented to the system, completing the loop.

In a healthy state, these parallel processes allow for appropriate and evolutionarily adaptive behavioral responses that can change depending on the valence, intensity, and relevance of stimuli. The BU loop, driven by reflexive, innate, emotional responses to stimuli, allows for rapid, immediate processing to respond to very threatening or very rewarding stimuli (Figure 2). As stimuli valence intensifies (more positive or negative), arousal generally increases, resulting in a higher likelihood of a behavioral response. The TD loop prevents unnecessary increases in arousal levels by filtering out stimuli that are neutral and irrelevant (Figure 2A).

(A–C, left) Flow of stimulus and valence processing in (A, left) healthy, (B, left) anxious, and (C, left) depressed states. Larger, thicker arrows indicate increased bias or activation. Dashed, thinner arrows indicate decreased activation.

(A–C, right) Valence processing curves. (A, right) In a healthy state, valence processing corresponds appropriately to increases in arousal and positive–negative valuations of valence. The dashed line indicates the threshold of responding to a given stimulus. (B, right) In an anxious state, arousal is increased with a negative valence bias. (C, right) In a depressed state, arousal is decreased with a negative valence bias.

ANXIETY DISORDERS CAN ORIGINATE FROM HYPERACTIVITY IN BOTTOM-UP REGIONS

BU processing at homeostatic levels is necessary for an animal to remain vigilant and cautious; however, pathological increases of activity in areas associated with adaptive anxiety processing can lead to maladaptive anxiety symptoms and behavior. Within the context of BU processing, the amygdala is a critical region in the brain for associative learning, BU processing, and arousal. The amygdala is also involved in processing changes in the internal state as an important interoception axis. What must be noted is the theorized bidirectional relationship between interoception and emotional arousal. As internal states change, emotions may arouse through conscious or subconscious evaluation of these homeostatic deviations. This interplay between internal state and emotional response reflects classic theories of emotion and illustrates how amygdala activity can simultaneously reflect interoceptive and emotional status. As evidenced by experiments in humans, patients with amygdalar insults struggle to generate physiological responses in anticipation of risky behavior or in response to losing in a gambling task. Further human behavior experiments show that associative processing related to emotion is also impaired—patients with amygdala lesions fail to recognize fearful emotions in faces, although they can decipher personal identity.

DEPRESSION MAY EMERGE FROM HYPERACTIVITY IN TOP-DOWN REGIONS

The mPFC has been historically linked to mood disorders and connectivity within this region has been implicated in depression. Encoding in the mPFC is attributed to reward learning, emotional memory, decision making, and moral assessment. Patients with vmPFC lesions exhibit impaired strategic decision making and intuitive moral judgment, suggesting that the mPFC plays a critical role in TD processing. Activity in the frontal cortices, specifically the anterior cingulate cortex, is associated with increased optimism and likelihood to imagine positive future outcomes, suggesting that the mPFC is required for long-term mediation that is characteristic of TD processing. Experimental and functional imaging studies have demonstrated dramatic changes focused on the PFC in depression. MDD has been associated with hyperactivation of the mPFC and reduced activation in reward-processing dopaminergic neurons in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). […]

What is also of importance are the connections between the mPFC and other regions, namely, the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and lateral habenula (LHb). The VTA is highly associated with reward and motivated behavior, whereas chronic inhibition of VTA–dopamine (DA) neurons induces depressive-like symptoms. Activity in the VTA is also susceptible to stress on different timescales—acute stress increases VTA neurons projecting to the mPFC, while chronic stress depresses VTA–mPFC activity.

OSCILLATORY ACTIVITY AS A DRIVER FOR TOP-DOWN/BOTTOM-UP BALANCE

Proper attention to stimuli relies on a healthy balance of TD and BU processing. In contrast, salient stimuli are processed in a BU fashion through sensory inputs, deliberate TD control of attention allows one to focus not only on vestibular senses but also on the long-term evaluation of these stimuli.

Oscillatory activity in the brain refers to the rhythmic and synchronously phase-locked activity between brain regions. This synchrony allows for distant brain regions to communicate and hold long-term information for conscious problem-solving by linking the information in these regions via a temporal framework. In both humans and monkeys, local field potential (LFP) gamma frequency (25–140 Hz) coherence between the PFC and visual cortex drastically increases during attention to a visual stimulus, implicating a concerted role of the mPFC for driving long-term attention. This type of oscillatory activity also provides the PFC with the ability to represent a variety of distinct categories of information in concert, allowing for more complex working memory.

Many disparate subfields interface with mental health disorders, from computational psychology to neuropharmacology to modern circuit neuroscience, yet they are poorly integrated.

This review article linked the computational, algorithmic, and implementational levels of investigation to connect the conceptual frameworks posited by each field.

On a computational level, the function of the mind in health and disease can be compared to attractor states, analogous to brain states.

On an algorithmic level, we explore how TD or BU brain states represent psychological processing pathways that are mediated by neural circuits.

On an implementational level, we can probe the way synaptic changes can alter neural dynamics and shift brain states along multiple distinct parameters.

The review presents a framework through which to understand and decipher the differences observed in anxious and depressed subjects based on behavioral and neural readouts.

To forge a path forward amidst the last frontier of our understanding—ourselves—we must integrate and synthesize the diverse perspectives for investigating psychiatric disease.