When babies first begin to talk, their vocabulary is very limited. Often one of the first sounds they generate is “da,” which may refer to dad, a dog, a dot, or nothing at all.

How does an adult listener make sense of this limited verbal repertoire? A new study “How adults understand what young children say” has found that adults’ understanding of conversational context and knowledge of mispronunciations that children commonly make are critical to the ability to understand children’s early linguistic efforts.

The research team created computational models that let them start to reverse engineer how adults interpret what small children are saying. Models based on only the actual sounds children produced in their speech did a relatively poor job predicting what adults thought children said. The most successful models made their predictions based on large swaths of preceding conversations that provided context for what the children were saying. The models also performed better when they were retrained on large datasets of adults and children interacting.

The findings suggest that adults are highly skilled at making these context-based interpretations, which may provide crucial feedback that helps babies acquire language.

“An adult with lots of listening experience is bringing to bear extremely sophisticated mechanisms of language understanding, and that is clearly what underlies the ability to understand what young children say,”

Roger Levy

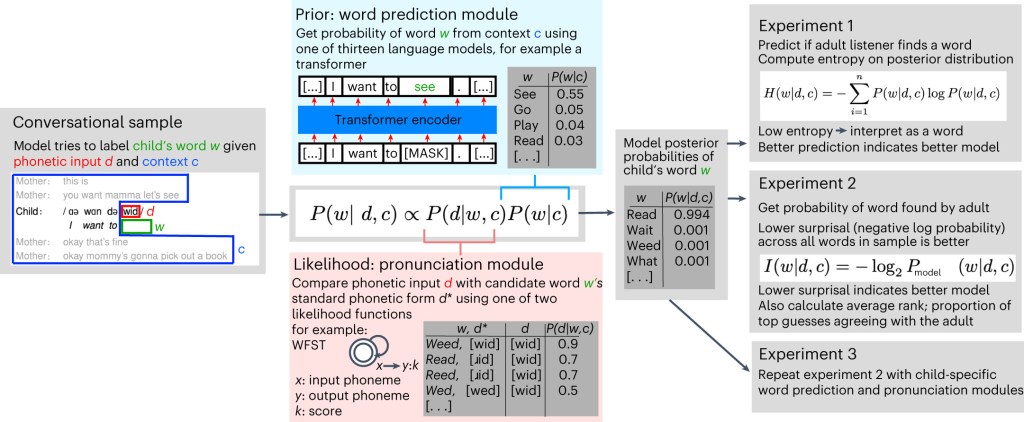

Models take phonetic transcripts of child speech as input and try to predict the adult interpretation using the surrounding context and the phonetic signal provided by the child.

Each model makes use of (i) a prior (light blue box), in the form of a probabilistic language model that predicts the word identity w based on the context c; and (ii) a probabilistic pronunciation model (light pink box). The prior and likelihood are combined using Bayesian inference to form a posterior distribution (light gray box) over candidate words w given c and d.

This posterior is evaluated against human annotations in two ways: first, how well it predicts whether an adult listener takes the input to be an intelligible word or treats it as unintelligible (Expt. 1); second, for intelligible input, how well it predicts which word is found by the adult listener (Expt. 2). We then test models tuned to specific children to see if adults tune to aspects of the speech of specific children (Expt. 3).

“At this point, we don’t have direct evidence that those mechanisms are directly facilitating the bootstrapping of language acquisition in young children, but it’s plausible to hypothesize that they are making the bootstrapping more effective and smoothing the path to successful language acquisition by children.”

In Panel a, all models use the Phoneme-Specific likelihood in the pronunciation module. The solid line with slope = 1 indicates chance performance. A larger area under the curve (AUC) corresponds to better classification performance.

Panel b compares classification performance of the two likelihoods. Every model with a Phoneme Specific likelihood (solid lines) outperforms the analogous one using the Edit-Distance likelihood (dotted lines).

“Most people prefer to talk to others, and I think babies are no exception to this, especially if there are things that they might want, either in a tangible way, like milk or to be picked up, but also in an intangible way in terms of just the spotlight of social attention. It’s a feedback system that might push the kid, with their burgeoning social skills and cognitive skills and everything else, to continue down this path of trying to interact and communicate.”

Elika Bergelson

This research finds strong evidence that context-specific beliefs about what children are likely to say are critical for replicating adult interpretations of noisy child speech.

There is further evidence of child-specific adaptation: models that are fine-tuned to the pronunciations, topics, constructions, and word choices of specific children yield even better approximations of adult interpretations of those children’s speech. This research paves the way for new avenues of inquiry into how children become mature language users through the contributions of adult listeners.