Dysfunctional breathing disorder(s) (DBD) is an umbrella term for a set of poorly distinguishable clinical conditions including the most emblematic and anciently known hyperventilation syndrome. DBD affects in a variable proportion (between 5 and 35%) both adults and children, with a highly negative impact on health-related quality of life. DBD is consensually considered as a condition encompassing one or several forms of altered breathing pattern (dysfunctional breathing) associated with an array of intermittent or chronic symptoms that may be respiratory, notably dyspnea, and/or non-respiratory in the absence or in excess of, organic disease.

Highly convincing recent work suggests some of the before-mentioned concerns regarding DBD may actually correspond to a more wide-ranging conceptual issue, namely our current implicit view of symptom perception in general, i.e., considering symptoms as resulting from perception of physiological changes within the body via a direct bottom-up sensory input. Indeed, during the latest decades, symptom perception has been put in broader and more complex frameworks, notably by an alternative ground-braking model, the Bayesian brain hypothesis. Paradoxically however, these new insights are mostly overlooked in daily clinical practice.

The article “Puzzled by dysfunctional breathing disorder(s)? Consider the Bayesian brain hypothesis! ” by Claudine Peiffer tries to show why and how the Bayesian brain hypothesis appears to be an ideal model to explain the many different aspects of DBD that remained hitherto obscure and difficult to explain.

(A) general principles of the model and

(B) its application to dysfunctional breathing disorder(s) (DBD).

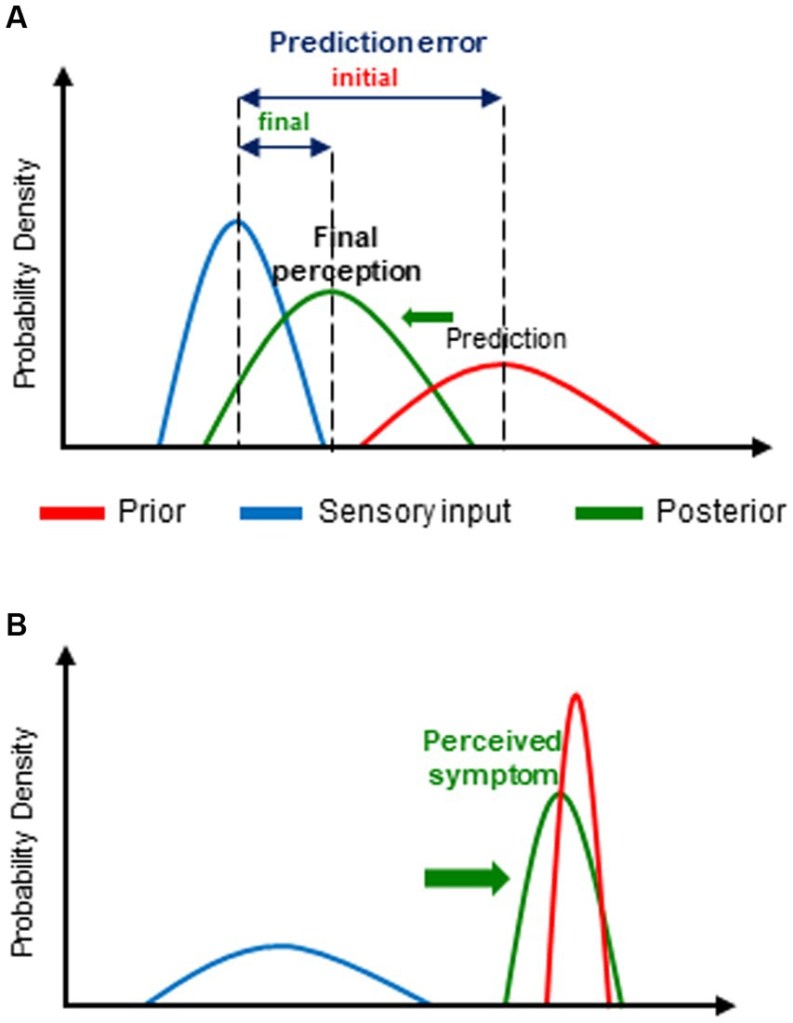

(A) For the purpose of prediction error minimization, the initial prediction or expectation (prior) is updated in the light of new incoming information (sensory input). The resulting updated posterior belief (posterior) (and thereby, the corresponding conscious perception) is crucially determined by the relative weight, i.e., the precision, of the prior and of sensory input. Thus, the posterior is predominantly influenced by biased toward (→) the one of its 2 determinants with the highest precision (i.e., the narrowest distribution of its expected values). Each parameter is represented by its corresponding probability distribution.

(B) In the case of DBD, the prior (prediction) is mostly abnormally precise and/or the sensory (physiological) input imprecise. Consequently, the posterior, i.e., the actually perceived symptom, is predominantly determined by the prior (that, moreover, is often erroneous).

The fundamental principle of the Bayesian brain hypothesis (BBH) is based on Bayes’ theorem. The latter allows to determine the posterior probability (posterior) of a hypothesis given prior beliefs about its probability (prior) and the likelihood of relevant associated data, by an operation called Bayesian inference. The conceptual framework of the BBH further relies on the still-relevant hypothesis of von Helmholtz who first submitted in the nineteenth century that perception is an unconscious inference of the causes of sensation and includes the “free energy principle” as well as relevant theoretical input from recent hypotheses and models of interoception. Since a few decades, there is increasing body of evidence from research in neuroscience, notably the seminal work of Friston, that Bayesian inference is a fundamental characteristic of brain function – referred to as Bayesian predictive coding (BPC).

This hypothesis submits that, rather than being a neutral receptor of sensory input from the inner and/or outer world, to which it has no direct access, the brain is actually an active inference machine that generates unconscious predictions about the most likely causes of that sensory input (priors) which are compared with actual incoming sensory input. Priors are based on innate homeostatic values but predominantly, on expectation and beliefs themselves grounded on past experience and associative learning and on contextual cues. In the case of difference (mismatch) between the prior (predicted sensory input) and the input actually received, a prediction error (an error signal of unexpected sensory input or surprise) is generated. The latter leads to an update of the prior by improving prediction and thereby, to the formation of a so-called posterior that determines the final conscious perception, and in turn, will be the new prior for a subsequent sensory event. This update consists of minimizing as much as possible the corresponding prediction error either by modifying the prior (by changing “expectations”) or by the way it samples afferent sensory information. Maximal reduction of prediction errors (i.e., sensory surprise) is indeed a fundamental characteristic of brain function based on the “free energy principle,” a basic property of biological (self-organizing) systems, i.e., resistance against the tendency to entropy (disorder).

Furthermore, the probabilistic nature of all the different components of the BPC process allows the brain to deal with uncertainty, an important feature of neural processing, in this case, uncertainty regarding prediction of sensory input by the prior, the sensory input itself (i.e., its signal to noise ratio) as well as associated prediction errors. The highest precision (highest weight or lowest uncertainty) is associated with the narrowest distribution of the probability of occurrence (likelihood) of a range of possible values of each of these variables. Precision and expected precision of the latter have a major impact on the final conscious perception. Indeed, the final posterior belief is biased toward the one of its determinants (prior belief and actual sensory input) with the highest precision.

Each given sensory input may generate a great number of different posterior beliefs, and ultimately, conscious perceptions, according to the different combinations of the relative precisions of the prior and the sensory input. Furthermore, the precision of the prior and of sensory input and thereby, their relative contribution to the posterior, are highly dependent on both contextual and individual factors which essentially impacts the way how the final perception is consciously experienced. Contextual factors and cues include attention as well as conscious personal expectations and beliefs, themselves related to personal history as well as to the cultural and social backgrounds, whereas individual factors include personality traits, especially negative affect, gender and genetic factors. Thus, for the crucial formation of the final perceptual construct, the BPC process involves also conscious high-ordered cognitive processes including interpretations (attribution of significance, hedonic and affective tone to sensory input) as well as expectation and beliefs involving associative learning all of them also contributing to the unconscious prior formation.

Moreover, according to the BPC model, the corresponding neuro-cognitive process is hierarchically organized, i.e., it takes place within and between multiple hierarchically structured and interacting cortical levels.

This consists of a main (first-order) continuous, bi-directional flow of information through these levels running from lower to higher areas and backward from higher to lower of information through these levels, i.e., ascending (bottom-up) prediction errors related to sensory input and descending (top-down) predictions (priors) that are progressively updated. At each of these hierarchical levels, the prior is compared to sensory input with formation of a prediction error that is send to the level above to form a new posterior that will constitute the updated prior for the level below.

The basic properties of incoming information are processed at lower hierarchical levels and its more complex and abstract aspects at the highest ones.

Throughout this hierarchical process up to the highest level of integration (final estimate of the brain), priors are progressively refined as to obtain the most reliable prediction (optimal guess) of sensory input. In this respect, it is important to emphasize that the information actually conveyed by this ascending flow through the different hierarchical levels is the prediction error related to sensory input rather than the whole sensory information. i.e.; only its unpredictable part is computed since the remaining sensory information is already contained in the prediction. Thereby, the brain avoids unnecessary computational work with redundant information as well as neural signaling delay, which in turn, allows adaptive behavior and potentially life-saving anticipation.

Furthermore, the BPC model submits the presence of an additional (second-order) bi-directional flow of information dealing with the precision of prediction errors and of lateral connections within each hierarchical level.

Interestingly, in the context of proprioception, agranular visceromotor regions (where priors are generated) are considered to be relatively insensitive to prediction errors thus highlighting again the predominant role of prediction in the final percept resulting from the BPC process. Likewise, precision corresponds to the activity of specific cells that modulate—mostly increase—synaptic gain (i.e., post-synaptic responsiveness) of cells encoding predictions and prediction errors. In functional motor and sensory symptoms, this increased gain has been shown to be related to misdirected attention from higher-level.

BBH provides a highly innovating explanatory framework for the underlying mechanisms of a number of clinical conditions, i.e., basically, an alteration of the BPC process regarding precision weights of priors relative to sensory input and metacognitive interpretation of this input . This explanatory model has been applied to neuropsychiatric disorders that are characterized by, or associated with abnormal concepts (delusion) or/and sensations, e.g., hallucinations and illusions and/or movements and most interestingly, to scFS (so-called functional syndromes) or equivalent.

The BBH model—including similar theoretical frameworks that are more specifically focused on interoception and symptom perception provide an innovative and powerful explanatory framework for the underlying mechanisms of the scFS including DBD.

DBD, can be reasonably considered as being part of the scFS nebula. Thus, for the symptom formation and perception of all the corresponding clinical conditions, the BBH submits a unifying pattern of altered BPC process. The latter consists basically of erroneous predictive coding, i.e., false inferences, that are mainly related to abnormally precise and mostly erroneous priors but also to, and interacting with imprecise physiological input both leading to a predominant influence of prior beliefs upon final perception (Figure B). These abnormal prior beliefs, are predominantly related to altered health beliefs involving several high-ordered conscious cognitive processes such as expectation of incoming health problems and ultimately, erroneous attribution of threatening health problem as the most likely cause of—sometimes minor—changes in physiological input. Interestingly, the relative contribution of priors, and consequently, that of contextual cues (leading to learned associations with symptoms) tends to increase over time, typically in long-lasting symptoms as scFS and presumably DBD, and may thereby explain their progressive decoupling from initial physiological input and potentially contribute to the perpetuation of these clinical conditions.

The alteration of the BPC process,by imprecise physiological input, has been attributed to several factors including poor interoceptive abilities in scFS patients, as well as, here again, in otherwise healthy high symptom reporters, expectation of imprecise physiological input, as well as to an increased activation of affective networks.

Most of the before-mentioned aspects of the altered BPC process may explain several of every-day clinical observations in DBD patients. Likewise, the underlying mechanisms of the alteration of the BPC process, i.e., imprecise physiological input may explain several clinical observations in DBD patients, such as the so-called disproportional dyspnea, i.e., high intensity of dyspnea in case of low intensity physiological input may be related to the low precision of that input.

It further may explain the a priori counterintuitive observation that anxious, hyper-vigilant and health and body-focused subjects are less accurate in their perceptual abilities.

“even if one keeps in mind that the BBH is only a model, i.e., the best possible explanation at a given historical moment, it is undoubtfully a major step forwards in our understanding of DBD and its numerous related symptoms, thereby contributing to improve our management of this complex and distressing clinical condition.”

Claudine Peiffer

One response to “Puzzled …? – Consider the Bayesian brain hypothesis!”

[…] of arousal, which in turn could provide evidence for fear or excitement, depending on the context. Each of these models is thought to consume energy, a finite resource, leading to competition within the organism for an […]

LikeLike