Trade-offs between producing costly movements for gathering information (‘explore’) and using previously acquired information to achieve a goal (‘exploit’) arise in a wide variety of problems, including foraging, reinforcement learning and sensorimotor control.

Determining the optimal balance between exploration and exploitation is computationally intractable, necessitating heuristic solutions.

In “Mode switching in organisms for solving explore-versus-exploit problem“, the authors show that the electric fish Eigenmannia virescens uses a salience-dependent mode-switching strategy to solve the explore–exploit conflict during a refuge-tracking task in which the same category of movement (fore-aft swimming) is used for both gathering information and achieving task goals. The fish produced distinctive non-Gaussian distributions of movement velocities characterized by sharp peaks for slower, task-oriented ‘exploit’ movements and broad shoulders for faster ‘explore’ movements. The measures of non-normality increased with increased sensory salience, corresponding to a decrease in the prevalence of fast explore movements.

The same sensory salience-dependent mode-switching behaviour is found across ten phylogenetically diverse organisms, from amoebae to humans, performing tasks such as postural balance and target tracking.

The authors propose a state-uncertainty-based mode-switching heuristic that reproduces the distinctive velocity distribution, rationalizes modulation by sensory salience and outperforms the classic persistent excitation approach while using less energy.

This mode-switching heuristic provides insights into purposeful exploratory behaviours in organisms, as well as a framework for more efficient state estimation and control of robots.

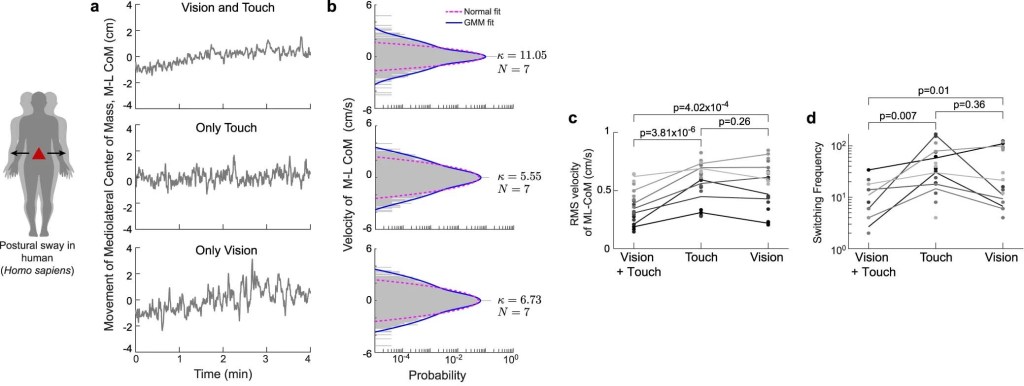

a, Postural sway in humans (Homo sapiens) during maintenance of quiet upright stance

b, Microsaccades in humans (H. sapiens) during fixated gaze

c, Bilateral eye movements in mice (M. musculus) during prey (cricket) capture

d, Pinnae movements in big brown bats (E. fuscus) while echolocating prey (mealworm)

e, Olfactory-driven head movements in eastern moles (S. aquaticus) in response to food (earthworms)

f, Odour plume tracking in American cockroaches (P. americana) in response to sex pheromone (periplanone B)

g, Tactile sensing by Carolina sphinx hawkmoth (M. sexta) while searching for a flower nectary

h, Visual tracking of swaying flower by hawkmoths

The second column shows representative temporal traces of the active exploratory movements and the third column shows the respective velocity traces. The fourth column presents velocity histograms showing that, unlike the normal distribution (magenta dashed curve), the three-component GMM (blue solid curve) captures the broad-shouldered nature of the velocity data across species, behaviours and sensing modalities.

Resolving this conflict between explore movements versus goal-directed exploit movements is a computationally intractable optimization problem. How do organisms resolve the explore–exploit conflict? A simple heuristic to solve this problem would be for an organism to perform goal-directed exploit movements while superimposing continuous small exploratory sensing movements—in other words, to use a persistent excitation approach. Indeed, this heuristic has proven effective (if suboptimal) as an engineering approach to solve the explore–exploit problem of identifying states and parameters of a dynamical system during task execution. If organisms were to employ such a strategy, they would produce movement statistics that correspond to a single behavioural mode (for example, a single-component Gaussian distribution) that continuously superimposes explore and exploit behaviour.

In contrast, we discovered that E. virescens does not use a persistent excitation strategy; instead, it shows a mode-switching strategy between fast, active-sensing movements (explore) and slow, corrective movements (exploit).

The modeling significantly better approximated by three-component Gaussian mixture models (GMMs) than by single-component models. The three-component GMMs generally comprised a sharp central Gaussian peak, capturing slow, task-oriented station-keeping movements, and two Gaussian ‘shoulders’, capturing faster, positive (forwards) and negative (backwards) exploratory movements. Only modest improvements in the fit of the GMMs occurred when using more than three components.

To assess the generality of this mode-switching strategy we investigated ten additional tasks performed by ten species ranging from amoebae to humans, using five major sensing modalities—vision, audition, olfaction, tactile sensing and electrosensation.

A broad phylogenetic array of organisms perform a variety of behavioural tasks using different control and morphophysiological systems. Just as these behavioural systems evolved within each of the lineages represented in our reanalyses, we suggest that mode switching probably evolved independently in each lineage as well. In other words, the similarities we found across taxa are the result of convergent evolution towards a common solution—mode switching—for the explore-versus-exploit problem.

Why might animals use mode switching, rather than the simpler heuristic of applying continual, low-amplitude exploratory inputs used by control engineers?

Active exploration is essential for better tracking performance as it improves state estimation. But, there is a point of diminishing returns: although higher (more energetic) active excitation can result in excellent state estimation, there is a point beyond which these additional active-sensing movements lead to greater tracking errors.

On the basis of this extensive reanalysis, we found that such mode switching—and its dependence on sensory salience—is found across diverse behaviours, taxa and sensing modalities. Inspired by this widespread biological strategy, we propose an engineering heuristic for selecting behavioural modes based on state uncertainty, and show that this heuristic captures key features of mode switching found across organismal models.

Furthermore, we show that this mode-switching heuristic can achieve better task-level performance, and do so with less control effort, than the conventional persistent-excitation strategy.

(c,d) Comparison of the RMS velocities (c) and switching frequency (d) for different experimental conditions.

Different shades of gray denotes different human subjects.

“Surprisingly, active sensing is largely avoided in engineering design despite being ubiquitous in animals. The performance of engineered systems may benefit from the generation of movement for improved sensing.”

The explore–exploit trade-off arises from the need for active-state estimation in a subset of tasks in which movement is used both for acquisition of information and achieving task goals.

However, similar trade-offs arise in a wide variety of potentially more complex behaviours. For example, in foraging where the resources are found in patchy distributions, organisms balance the trade-offs between exploiting a local food source, exploring for distant sources and the costs of predation across the habitat.

Similarly, reinforcement learning involves choosing whether to adhere to a familiar option with a known reward or taking the risk to explore unknown options that can lead to increased rewards over the longer term. We do not have direct evidence that the broad-shouldered feature we have identified in animal movements described here—reflecting the manifestation of mode switching—are also be found in these behavioural domains across taxa.

Recent evidence from studies of human reinforcement learning, however, appear to be consistent with mode-switching behaviour.