On the face of it, wishful thinking seems incompatible with the Bayesian brain hypothesis.

This is why defenses of Bayesianism have taken an eliminative stance toward wishful thinking, showing that many apparent instances of wishful thinking are not wishful after all.

This strategy has succeeded in defeating many challenges to the Bayesian brain hypothesis, with at least one major exception: the phenomenon of wishful belief polarization. Instead of recasting wishful belief polarization in non-wishful terms, we have established that wishful belief polarization and Bayesianism are compatible. Data in this research support a fully Bayesian account of wishful belief polarization. In our model, when defending a position is incentivized, the motivation to obtain the incentive leads to better-than-predicted feelings about defending the position.

The resulting APE (affective prediction errors) is used to shift beliefs into alignment with the to-be-defended position—a process that is at once directionally motivated and Bayes-rational.

In addition to reconciling the Bayesian brain hypothesis with wishful thinking, the model advances theories

of how people use their feelings as information about the external world.

That people use their feelings as information is well-established, but accounts of the computational mechanisms underlying this process are in their infancy. Recent work suggests that feelings are used to update beliefs according to Bayesian principles.

Our work supports this idea by providing evidence that affect-based belief updating adheres to two predictions of

Bayesian optimality:

(i) it is a function not of affect per se, but of APEs, and

(ii) the noisier people think their affect is, the weaker the relationship between APEs and belief updating.

The results highlight the fact that Bayesian brains, though rational in one sense of the word, are perfectly capable of producing irrational output.

This is because the rationality of a Bayesian brain is limited to the structure of its learning process: It updates its beliefs rationally given the data it encounters and its current internal model. When fed false data, or when using a flawed internal model, Bayesian logic can produce irrational outcomes.

Here, the irrational outcome is wishful belief polarization, and the modeling flaw that seems to produce it is an overly pessimistic belief about how good it will feel to defend a position in the service of a desired outcome.

Where does this overly pessimistic belief come from, and why does it persist in the face of disconfirming evidence?

Why has a lifetime of learning not produced a more accurate internal model?

One possibility is that evolution has endowed people with an extremely strong prior that affect is more autocorrelated than it really is, and therefore less responsive than it really is to situational factors like incentives to advocate. This hypothesis is supported by decades of research on the projection bias, and fits comfortably in a Bayesian framework. It also raises a new question: Why would evolution select for an extremely strong and spuriously high prior on the autocorrelation of affect?

We suggest that such a prior is advantageous precisely because it drives wishful thinking, which often promotes adaptive behavior. People are more persuasive, for instance, when they actually believe what it is they are arguing.

Bayesian brains therefore stand to gain from believing in the positions they are incentivized to defend even if those positions defy the available evidence.

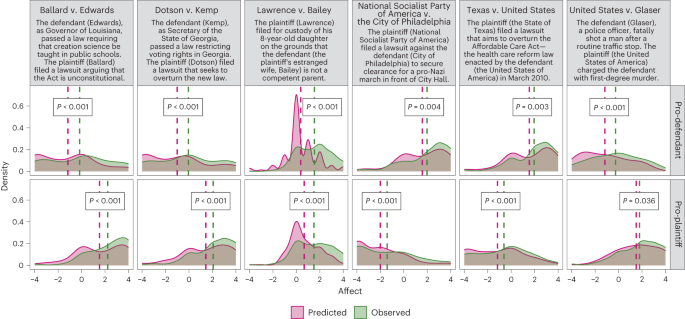

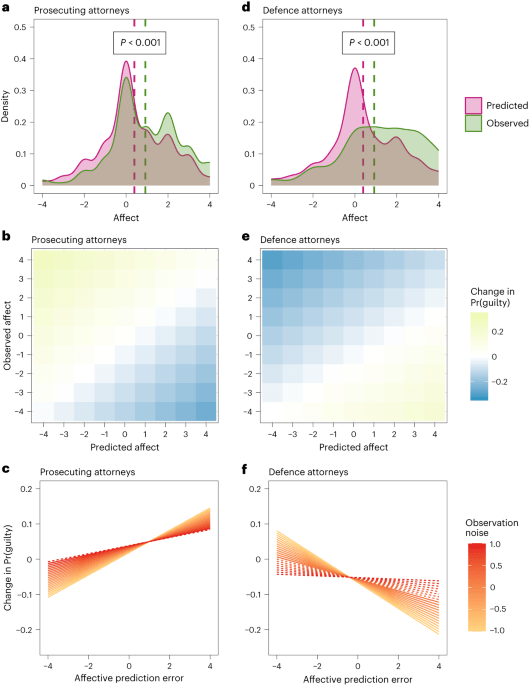

the position that Harriet is guilty.

B. Independent effects of predicted and observed affect on change in Pr(guilty).

C. Change in Pr(guilty) as a function of APEs (observed minus predicted affect) and subjective observation noise among prosecuting attorneys.

D. Predicted versus actual affect about defending the position that Harriet is innocent.

E. Independent effects of predicted and observed values

of affect on change in Pr(guilty).

F. Change in Pr(guilty) as a function of APEs and subjective observation noise among defense attorneys.

Another reason why affective predictions are so frequently wrong may be a failure to generalize appropriately.

If a person feels better-than-expected about defending a position in one specific context, that person may infer that their feelings are less autocorrelated than previously thought in that particular context, but not in general. This would lead to more accurate affective predictions in the context where the initial prediction error was encoded but not in other contexts.

There may be additional paths, besides the one uncovered here, from Bayesian inference to wishful belief polarization. One possibility that has been raised is that wishful belief polarization emerges from a strong prior

that nature is “benevolent,” or “rigged” in one’s favor.

Simulation studies have shown that if an agent holds this belief and observes that they would benefit from a particular event, the agent will conclude that the event will occur.

Perhaps the deepest question for future work is the one we started with: Is the brain Bayesian? The current investigation does not settle the issue, but it does lend support to proponents of the Bayesian approach by defending it against one of its greatest empirical challenges.

One response to “Bayesianism and Wishful Thinking are Compatible”

[…] This implies that decision-making, planning and information-seeking are, in a generic sense, ‘wishful’. We take an interdisciplinary perspective on this perplexing aspect of the free-energy principle […]

LikeLike