“Insight and the selection of ideas” describes the mechanisms underlying Eureka heuristic, explained within an active inference framework.

Perhaps it is no accident that insight moments accompany some of humanity’s most important discoveries in science, medicine, and art. Here we propose that feelings of insight play a central role in (heuristically) selecting an idea from the stream of consciousness by capturing attention and eliciting a sense of intuitive confidence permitting fast action under uncertainty.

First, implicit restructuring via Bayesian reduction leads to a higher-order prediction error (i.e., the content of insight).

Second, dopaminergic precision-weighting of the prediction error accounts for the intuitive confidence, pleasure, and attentional capture (i.e., the feeling of insight).

This insight as precision account is consistent with the phenomenology, accuracy, and neural unfolding of insight, as well as its effects on belief and decision-making.

| • Insights can heuristically select ideas from the stream of consciousness. • Prior learning and context drives insight veridicality. • The content of insight reflects a higher-order prediction error. • The feeling of insight reflects the dopaminergic precision of the prediction error. • Misinformation and psychoactive substances can bias insights and generate false beliefs. |

We do not just think about ideas, we feel them too. Whenever we listen to a presentation by a scientist (or a politician), we quickly sense whether we agree with the ideas being shared. The same is true for our own ideas. When an idea appears in our own minds, we also feel whether that idea is likely to be true, valuable, or exciting, and then decide whether to ignore it, share it with our colleagues, or abandon it. When a new idea comes to mind as insight it feels true and immediately imbues us with the sense that the idea is a good one.

According to feelings-as-information theory, phenomenology carries information that helps us to efficiently navigate the world and to reason appropriately

The insight experience has also been characterized as an emotional reaction regarding the relevance of a solution to the organism’s goals. This account frames insight as the result of combining novel neural representations, which result in further novel emotional neural representations that evaluate the idea in terms of its payoffs. One similarity here is that the insight experience is assigned a higher-order function.

Implicit processing is important because it highlights why an insight heuristic may be necessary. If an idea appears spontaneously following unconscious ‘work’, then there ought to be a way for the organism to judge whether the idea can be trusted.

One result requiring explanation is the fact that insights are characterized by higher accuracy. For example, 92% of the time people have an insight they are likely to be correct.

The feeling of insight and its intensity appears to have informational value about the accuracy of new ideas, which makes sense if coherence with past learning is partly driving the intensity of the insight experience.

[…] participants appeared to misattribute their Aha! experiences to the temporally coincident but irrelevant fact, suggesting that the feeling of Aha! influences one’s sense of what is considered ‘true’. We then extended this paradigm to axiomatic worldviews, such as “it is useless to pursue justice” or “free will is a powerful illusion”. […] we found that irrelevant Aha! moments lead to a ‘ring of truth’ that results in greater belief in the presented worldviews

The accuracy of the feeling of insight can be confounded by exposing the participants to misleading information, effectively breaking the heuristic (i.e., the extent to which past knowledge or context was accurately informing the phenomenology).

Considering the similarities between quickly switching attention to sudden inputs and the involvement of the LC-NE system ( locus coeruleus-norepinephrine), it is likely that the Aha! feeling aids the selection of ideas in awareness specifically by its ability to capture attention.

Eureka Heuristic integrates processes of the mind, brain, body, and behaviour, under a single process known as prediction-error minimization. As yet, the process of sudden discovery and ‘Aha!’ experiences that characterize insight have not been fully integrated under this Bayesian inferential view of mind. This framework shows promise as a context for understanding the dynamics and functions of the Aha! experience including the Eureka Heuristic.

“Fact free learning” rests on an assumption that the optimization of models (prediction-error minimization) can also occur without new information from outside the body. That is, no new facts are necessary for the system to continue refining its understanding. One can see how this is important for sudden learning events like insight, in which one can discover something seemingly novel while in the shower, or just before falling asleep. Fact free learning occurs through Bayesian model reduction—a simple and efficient form of Bayesian model selection.

Bayesian model reduction entails finding more parsimonious and generalizable explanations of the data already possessed. It is a kind of ‘active incubation’ where one’s knowledge is tested against itself—“only of itself and on itself’’ —in order to find simpler explanations.

The above account provides a candidate formal explanation of how a sudden discovery can emerge from unconscious processes. Crucially, however, the Bayesian reduction account does not explain the feeling or function of insight.

Bayesian model reduction only addresses the preceding implicit belief updating and selection processes (the transition from incubation to illumination). It does not account for the ‘experience’ of the Aha! moment and its downstream consequences.

Precision is associated with attention, confidence, and is believed to be encoded by neuromodulators like noradrenaline and dopamine —and therefore an idea with high precision ought to capture attention, feel right, feel good, and inspire confident action; either motor action or autonomic. Computational formulations in the context of decision-making indicate that the precision of beliefs about action reflects its expected value or utility, consistent with the secondary component of reward prediction errors. This fits comfortably with the fact that insights seem intrinsically valuable when they arise. An idea with low expected uncertainty (high precision) should also be objectively accurate on average given reliable prior and contextual knowledge, see Fig. 1. In some fields, this kind of (intrinsic) value is known as intrinsic motivation, of the sort that underwrites exploration and epistemic affordances.

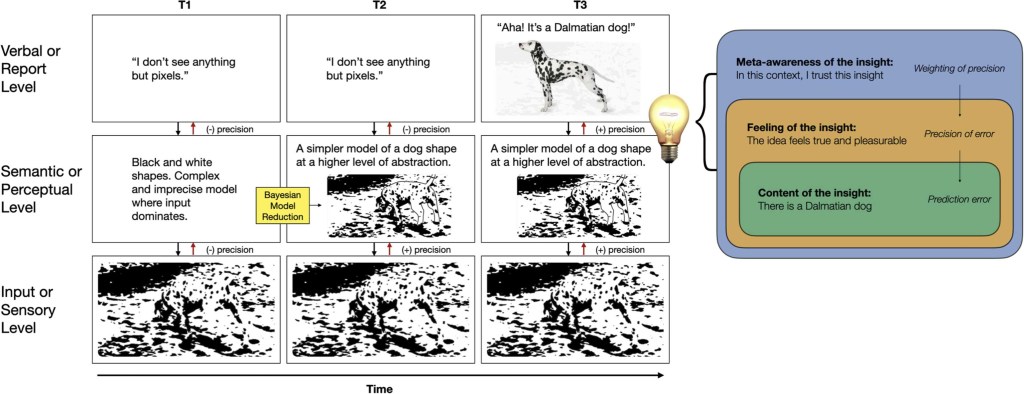

At the next “semantic or perceptual level” we see a change from T1 to T2 following Bayesian model reduction. A new simpler, less complex, and more parsimonious model of the black and white “blobs” or pixels emerges at a slightly higher level of abstraction (i.e., the shape of a dog).

At the highest verbal or report level we see a shift from T2 to T3 from “I don’t see anything but pixels” to a “Dalmatian dog!”: The reduced model of the Dalmatian dog leads to a precise prediction error and a corresponding Aha! experience as the higher-order verbal model restructures.

On the right side, we present additional nested levels of inference about the precision of an idea, which brings to light the role of meta-awareness in evaluating the reliability of feelings of insight.

Overall, the figure illustrates the gradual emergence of an insight through changes at different levels of the predictive hierarchy over time, involving Bayesian reduction and ascending precision-weighted prediction errors.

[…] in the case of insight, we have an idea, we also have a feeling about that idea, and we can also have a meta-awareness about the feeling (i.e., how confident am I that this feeling is trustworthy in this context?).

This next level of inference that corresponds to meta-awareness is simply another layer of precision-weighting over the feeling.

Such high-order representations of mental states are necessary to both recognise a quantitative change in ascending prediction errors and generate descending predictions of precision to instantiate an attentional set—a set that may be necessary to consolidate the insight and imbue it with a sense of veracity.

This high-order aspect of hierarchical predictive processing is the same architecture that has been proposed for phenomenal experience. Such high level representations are necessary to recognise various states of mind (e.g., mind-wandering or insight experiences) and upon which mental or covert action can be conditioned (e.g., what one pays attention to).

In this sense, the phenomenal experience is both cause and consequence; much in the same way that various affective states of mind recognise and cause interoceptive signals via interoceptive inference

Table: Aha moments as dopaminergic precision.

| Mechanism | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Precision reflects uncertainty given prior learning | Insights are accurate (on average) |

| Precision is experienced as felt confidence | Insights feel obvious and increase confidence |

| Dopaminergic modulation of precision | Insights feel pleasurable |

| Precision drives model selection | Insights affect beliefs Insights are remembered |

| Precision reflects attention and salience Precision prepares action | Insights capture attention and correlate with salience network activation Insights promote drive |

| Dopaminergic modulation of precision | Insights are associated with the reward system |

John Nash was famously asked why he believed that he was being recruited by aliens to save the world. He said that,

“…the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously”

His response powerfully illustrates the recursive danger of the Eureka heuristic.

The consequences of false insights can also be dire.

Consistent with the insight as precision framework, when an insight moment occurs, subjects are less likely to accept an alternative solution to the problem and are more likely to stick with, and remember, solutions that are similar to their insight. Insights also promote inspiration and provide a drive towards action, consistent with dopaminergic model selection. Thus, relative to an incorrect-but-analytically derived idea, when a false insight occurs, it may be more difficult to change the person’s mind and to prevent them from behaving as if the solution were true.

The word Eureka originates in Ancient Greece from the word εὕρηκα (heúrēka), and before that from heuriskein, which means “I find.”

Heuriskein is also the ancient origin of the word heuristic, which refers to shortcuts that help humans to solve problems.

The shared origin of the two words Eureka and heuristic may point to a forgotten wisdom about the nature of the insight experience, namely, that humans use the feeling of Eureka as a heuristic signal to help them select from myriad thoughts and ideas appearing in awareness.

To explain the mechanics of the heuristic, we have extended the computational framework of Bayesian model reduction to include the feeling of insight as dopaminergic precision; namely, felt uncertainty.

That is, insight may be derived through implicit Bayesian model optimization “…much like a sculpture is revealed by the artful removal of stone”.

From a decision-making perspective, Aha! moments therefore directly reflect reductions in expected epistemic uncertainty, making for a good heuristic.