Traditionally, resilience has been viewed as a general positive adaptation to stressors. However, the hallmark of resilience – returning to the previous state following a perturbation – may also have severe downsides, which are often overlooked.

Specifically, it may be unrealistic to return to the previous state or resilience may cause a person to become stuck in an undesirable state. In this article, we first call for a more nuanced theoretical conceptualization of resilience. To do so, we draw on insights from dynamical systems theory help to clearly define the role of a stressor and the idealized pathway to adapt to it. Then, we exemplify the potential downsides of resilience in the context of trauma and social adversity, learning, and goal-disengagement.

In conclusion, researchers and practitioners should become more cautious with the term resilience and provide nuanced accounts for what they mean to avoid potentially harmful consequences.

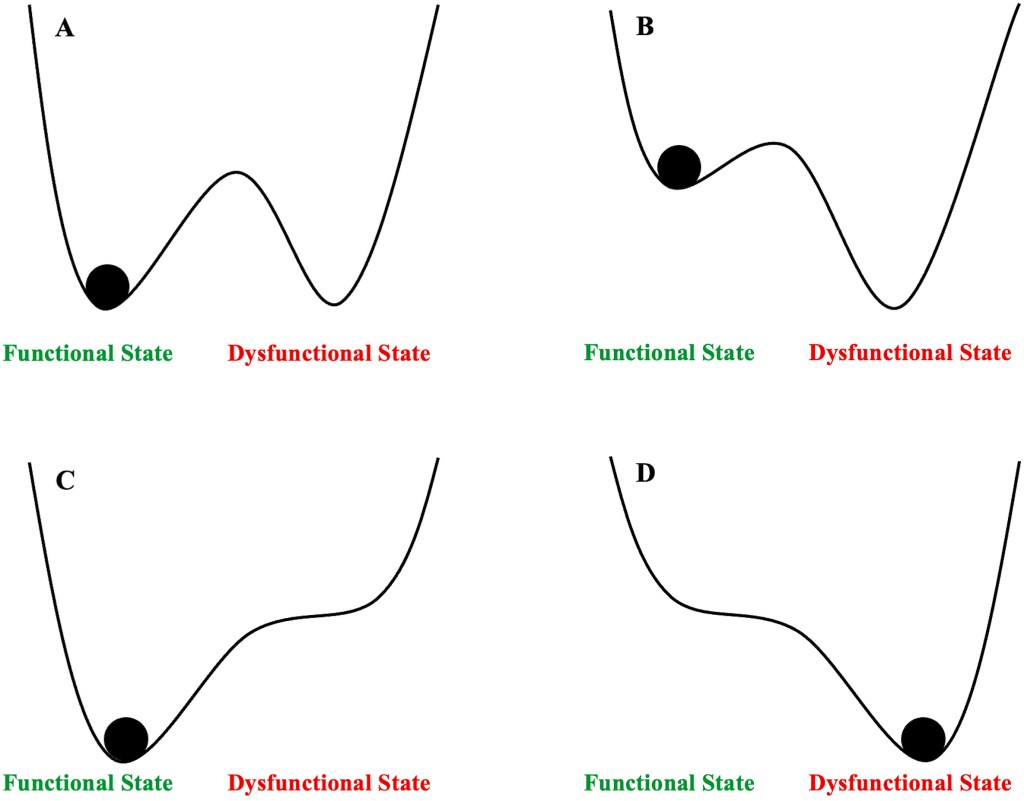

The current state of a person is represented by the ball within the landscape. In this example, the person resides in a functional state. The depth of the valley, measured from the top of the lowest adjacent peak to the bottom of the basin, determines the attractor’s strength. This means that the deeper the valley, the stronger a perturbation must be to move the ball out of the current state. If the perturbation is too small, the ball rolls back and re-stabilizes in the previous state (i.e., demonstrate resilience).

Fig. A displays a relatively strong attractor which is likely to demonstrate resilience following a perturbation. Note, however, that an equally strong dysfunctional state exists at the same time, although it is generally not accessible. If the perturbation is strong enough to move the ball to the dysfunctional state, the ball would stabilize in the dysfunctional state and an equally strong perturbation is needed to induce another shift.

In Fig. B, the attractor state is rather weak and a minor perturbation suffices to push the ball into the dysfunctional state. Furthermore, a much larger perturbation would be required to return the ball to the functional state.

In Fig. C, the dysfunctional state is so weak that the ball could never stabilize in this state. Thus, independent of the perturbation strength, the re-stabilization would occur in the functional state.

Conversely, people residing in a strong, undesirable state with no alternative state to stabilize in become stuck in the undesirable state (Fig. D).

(i.e., a projection of the three-dimensional “Lorenz butterfly”).

Although the system shows global stability – once in one of the two “wings” of the butterfly, the path never leaves the butterfly – the exact same state is never revisited. This means that a system producing a strange attractor is marked by fractal temporal structures. A strange attractor achieves global stability which is marked by local variability.

Cases of when resilience becomes undesirable:

- Harmful stressors: trauma and adversity

- Learning

- Goal-disengagement

The notion that resilience can potentially be undesirable also calls for some practical considerations for interventions. Some authors already called for caution regarding interventions aimed at improving resilience because these may have undesirable effects when the desired outcomes are not carefully specified. Similarly, promoting resilience in the form of returning to the previous behavioral or cognitive patterns in cases where different adaptations are necessary can be problematic.

Because the same level of functioning may be re-instated through alternative pathways, it is important to not only evaluate the level of functioning, but also how these states are achieved.

In line with the notion of the different attractor conceptualizations, an intervention may therefore seek to stabilize a desirable attractor, dissolve the existence of an undesirable attractor, or diversify the response patterns.

Although resilience is a desirable process in many contexts, it should not be considered as the ideal default response to every stressor. That is, the tendency to return to the previous level of functioning or associated cognitive and behavioral patterns can be dysfunctional.

Therefore, researchers and practitioners alike should be cautious when investigating or training resilience. More nuanced response patterns, such as functional adaptations through exploring new and alternative pathways may be warranted in various cases when people are at risk of becoming stuck in undesirable states. These nuanced theoretical differences also carry important implications regarding the specific aims of interventions for improving resilience.