The authors argue that many different biases, such as the bias blind spot, hostile media bias, egocentric/ethnocentric bias, and outcome bias, can be traced back to the combination of a fundamental prior belief and humans’ tendency toward belief-consistent information processing.

Thought creates the world and then says,

—David Bohm (physicist)

“I didn’t do it.”

One of the essential insights from psychological research is that people’s information processing is often biased. By now, a number of different biases have been identified and empirically demonstrated. Unfortunately, however, these biases have often been examined in separate lines of research, thereby precluding the recognition of shared principles.

Here we argue that several—so far mostly unrelated—biases (e.g., bias blind spot, hostile media bias, egocentric/ethnocentric bias, outcome bias) can be traced back to the combination of a fundamental prior belief and humans’ tendency toward belief-consistent information processing.

What varies between different biases is essentially the specific belief that guides information processing.

More importantly, we propose that different biases even share the same underlying belief and differ only in the specific outcome of information processing that is assessed (i.e., the dependent variable), thus tapping into different manifestations of the same latent information processing.

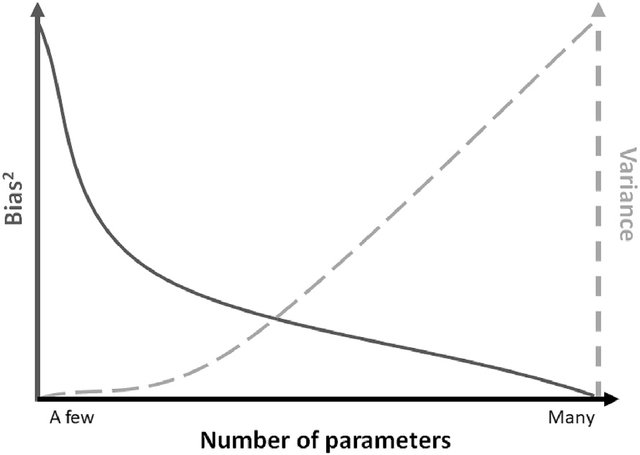

In other words, we propose for discussion a model that suffices to explain several different biases.

We thereby suggest a more parsimonious approach compared with current theoretical explanations of these biases. We also generate novel hypotheses that follow directly from the integrative nature of our perspective.

“I make correct assessments”

The main hypothesis (H1) is that several biases can be traced back to the same basic recipe of belief plus belief-consistent information processing. Undermining belief-consistent information processing (e.g., by successfully eliciting a search for belief-inconsistent information) should—according to this logic—attenuate biases. Thus, to the extent that an explicit instruction to “consider the opposite” (of the proposed underlying belief) is effective in undermining belief-consistent information processing, it should attenuate virtually any bias to which our recipe is applicable, even if this has not been documented in the literature so far. Thus, cumulative evidence that experimentally assigning such a strategy fails to reduce biases named here would speak against our model.

At the same time, we have proposed that several biases are actually based on the same beliefs, which leads to the assumption that biases sharing the same beliefs should show a positive correlation (or at least a stronger positive correlation than biases that are based on different beliefs, H2). Thus, collecting data from a whole battery of bias tasks would allow a confirmatory test of whether the underlying beliefs serve as organizing latent factors that can explain the correlations between the different bias manifestations.

Further hypotheses follow from the fact that there is a special case of a fundamental belief in that its content inherently relates to biases—the belief that one makes correct assessments. Essentially, it might be regarded as a kind of “g factor” of biases. Following from this, we expect natural (e.g., interindividual) or experimentally induced differences in the belief of making correct assessments (e.g., undermining it; for discussions on the phenomenon of gaslighting) to be mirrored not only in biases based on this but also other beliefs (H3). However, in consideration of the fact that we essentially regard several biases as a tendency to confirm the underlying fundamental belief (via belief-consistent information processing), “successfully” biased information processing should nourish the belief in one’s making correct assessments—as one’s prior beliefs have been confirmed (H4). For example, people who believe their group to be good and engage in belief-consistent information processing leading them to conclusions that confirm their belief are at the same time confirmed in their convictions that they make correct assessments of the world. The same should work for other biases such as the “better-than-average effect” or “outcome bias,” for instance. If I believe myself to be better than the average, for instance, and subsequently engage in confirmatory information processing by comparing myself with others who have lower abilities in the particular domain in question, this should strengthen my belief that I generally assess the world correctly. Likewise, if I believe that it is mainly peoples’ attributes that shape outcomes and—consistent with this belief—attribute a company’s failure to its CEO’s mismanagement, I get “confirmed” in my belief that I make correct assessments. Only if belief-consistent information processing failed would the belief that one makes correct assessments likewise not be nourished. This is, however, not extremely likely given the plethora of research showing that people may see confirmation of the basic belief even if there is actually none or only equivocal confirmation, let alone disconfirmation. If, however, engaging in any (other) form of bias expression would attenuate biases following from the belief of making correct assessments, this would strongly speak against our rationale.

There is one exception, however. If one was aware that one is processing information in a biased way and was unable to rationalize this proceeding, biases should not be expressed because it would threaten one’s belief in making correct assessments. In other words, the belief in making correct assessments should constrain biases based on other beliefs because people are rather motivated to maintain an illusion of objectivity regarding the manner in which they derived their inferences. Thus, there is a constraint on motivated information processing: People need to be able to justify their conclusions. If people were stripped of this possibility, that is, if they were not able to justify their biased information processing (e.g., because they are made aware of their potential bias and fear that others could become aware of it as well), we should observe attempts to reduce that particular bias and an effective reduction if people knew how to correct for it (H5).

Above and beyond these rather general hypotheses, further corollaries of our account unfold. For instance, we would expect the same group favoritism for groups people do not belong to and identify with but which they believe to be good (H6). This hypothesis would not be predicted by the social-identity approach, which is most commonly referred to when explaining in-group favoritism.

To put it briefly, theoretical advancements necessitate integration and parsimony (the integrative potential), as well as novel ideas and hypotheses (the generative potential).

We believe that the proposed framework for understanding bias as presented in this article has merits in both of these aspects. We hope to instigate discussion as well as empirical scrutiny with the ultimate goal of identifying common principles across several disparate research strands that have heretofore sought to understand human biases.