“Predecisional information search adaptively reduces three types

of uncertainty“

How do people search for information when they are given the opportunity to freely explore their options?

Information search is an integral part of the decision-making process. Every choice we make is based on information that must first be obtained. In many cases, information search is inherently consequential. For example, in trying out a new restaurant, we forgo the opportunity to eat at our favorite place around the corner.

How people navigate this balance between maximizing short-term gains and obtaining new information that can be useful in the long run has been thoroughly investigated.

However, information search is not always consequential. Modern information technology is creating ever-more opportunities to freely explore the available options before coming to a consequential decision: We can consult online restaurant reviews, use internet platforms to study the development of financial investments, or use simulations to learn about the dangers of diseases before making a decision. What drives information search in these situations?

Previous research has suggested that people focus on reducing uncertainty before making a decision, but it remains unclear how exactly they do so and whether they do so consistently.

We present an analysis of over 1,000,000 information-search decisions made by over 2,500 individuals in a decisions-from experience setting that cleanly separates information search from choice. Using a data driven approach supported by a formal measurement framework, we examine how people allocate samples to options and how they decide to terminate search.

Three major insights emerge.

First, predecisional information search has at least three drivers that can be interpreted as reducing three types of uncertainty:

structural, estimation, and computational.

Second, the selection of these drivers of information search is adaptive, sequential, and guided by environmental knowledge that integrates prior expectations, task instructions, and personal experiences.

Third, predecisional information search exhibits substantial interindividual heterogeneity, with individuals recruiting different drivers of information search.

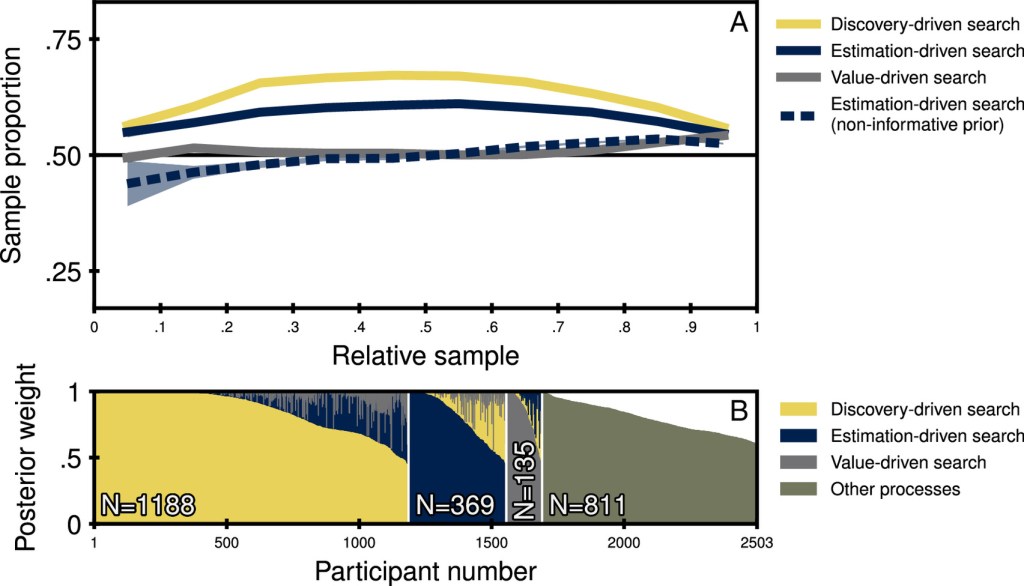

Panel (A) shows the proportion of sample-allocation decisions consistent with value-driven search (blue), estimation-driven search (gray), and discovery-driven search (yellow) as a function of the position of a sample within the sampling sequence (relative sample). All three model-based measures were aggregated across all participants and problems.

Shaded areas indicate the 95% CI.

Panel (B) shows the posterior weights for each individual and driver of information search. The x-axis is separated into four groups, depending on the predominant driver. Within each group, individuals are sorted in descending order by the posterior weight of that driver. The last group consists of individuals who were not described by any of the drivers above chance level. Here, the heights of the bars reflect the posterior mean of the error parameter.

Our analysis also showed that people engage in search that is informed by their prior expectations and environmental knowledge. People seem to transition from reducing structural uncertainty (via discovery-driven search) to reducing estimation uncertainty as soon as the former has been achieved. It is highly likely that people accumulate knowledge about the structure of the task environment by integrating prior expectations, study

instructions, and observed outcomes, and that they use this knowledge and experience to inform their subsequent information search. One possible algorithmic implementation of such knowledge acquisition is given in the prior of our measurement framework, which reflects the idea that people learn about the options typically encountered and their values. However, given that this prior did not fully close the gap between estimation and discovery-driven search, it seems that people’s environmental knowledge extends beyond the estimation of values and is also likely to include the number and kinds of outcomes to expect.

Together, these insights suggest that human information search is complex in ways that cannot be fully explained by monolithic accounts of

information search, including proposals focused on estimation uncertainty or cost–benefit analysis.

We conclude that broader theories of human information-search

behavior are necessary.

There is a growing body of work showing adaptive behavior in related domains.

We hope that future efforts to model and study information search will account for the diversity of behavior and thought that ensues from people’s creative approaches to information search.