“Going beyond the AHA! moment: insight discovery for transdisciplinary research and learning“

The concept of ‘insight discovery’ is developed as a key competence for transdisciplinary research and learning in this paper.

To address complex societal and environmental problems facing the world today, a particular expertise that can identify new connections between diverse knowledge fields is needed in order to integrate diverse perspectives from a wide range of stakeholders and develop novel solutions.

The capacity for “insight discovery” means becoming aware of personal mental representations of the world and being able to shape and integrate perspectives different from one’s own.

Based on experiences and empirical observations within the scope of an educational programme for Masters students, PhD candidates and post-doctoral researchers, we suggest that insights are the outcome of a learning process influenced by the collective and environment in which they are conceived, rather than instant moments of individual brilliance.

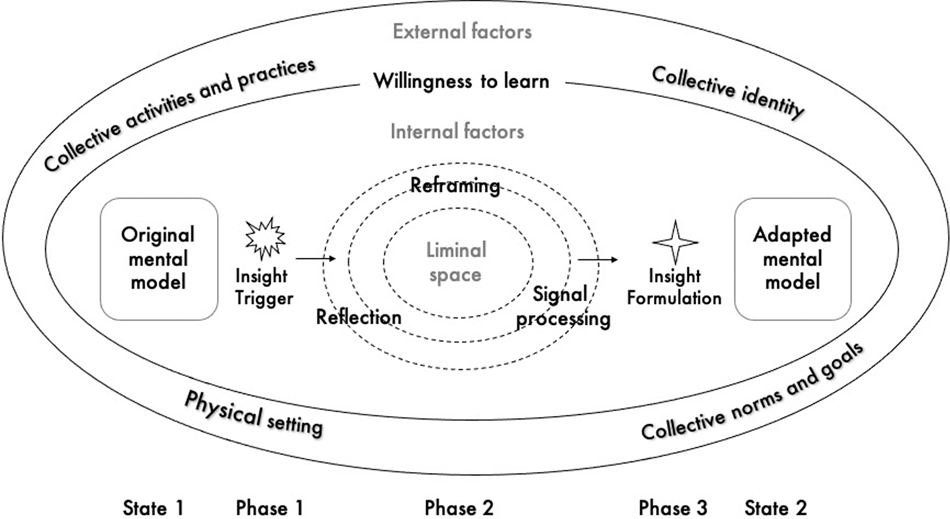

The process which we describe, named the insight discovery process, is made up of five aspects. Within a group setting, a person begins with an “original mental model”, experiences an “insight trigger”, processes new information within the “liminal space”, “formulates an insight” and eventually forms an “adapted mental model”.

There is a potential for incorporating such process as a fundamental competence for transdisciplinary curricula in undergraduate and graduate programmes by cultivating specific practices and safe learning environments, focused on the enquiry, exchange and integration of diverse perspectives.

The process begins with the original mental model (State 1), which is disrupted by an insight trigger (Phase 1), moves into a liminal space characterised by reframing, reflecting and signal processing (Phase 2), leads to insight formulation (Phase 3) which contributes to an adapted mental model of the problem or situation (State 2).

insights are the outcome of a learning process influenced by the collective and environment in which they are conceived, rather than instant moments of individual brilliance.

Different authors have referred to problems as “wicked”, “complex” or “ill-defined”. A common characteristic of this type of problem is that its definition depends on the perspective of the individual confronting the problem.

What enables effective engagement with this complexity is “insight discovery”, defined as the ability and willingness to identify and overturn one’s own assumptions by assimilating new experiences and knowledge. They require “new ways of knowledge production”, learning from a wide range of disciplines and the inclusion of knowledge from outside of academia.

One way to address these questions is to foster a willingness and capacity for discovering and acting on insights. The focus of this “insight discovery process” (IDP) is not only on acquiring a greater quantity of information, but on improving how we can better interpret information that is already available to us.

A dictionary definition of “insight” is the “capacity to gain an accurate and deep understanding of someone or something”. Common terms associated with insights include—the “AHA! Moment”, the “Eureka Moment”, the “lightbulb moment” or a “flash of illumination”.

The concept of “insight” as a research subject was introduced in the 1920s in Austria and Germany by Gestalt psychologists interested in understanding the process of problem solving. This work revealed that people solved problems by restructuring available information that, suddenly, leads to the emergence of a new understanding.

When taken into the context of complex problem solving in groups, there is an opportunity to further develop the insight concept in relation to the process of joint problem framing in transdisciplinary research.

Problem framing is the process of eliciting, searching and selecting relevant perspectives that restructure one’s perception of a situation, to determine the appropriate goals and criteria for the creation of effective solutions. Joint problem framing takes place in a group setting, when diverse points of views are integrated to create a shared understanding of a problem and its possible solutions.

The integration is made possible when individuals are open to changing their individual mental representation of the problem—their mental model—by identifying, exchanging and incorporating insights from inside and outside the group such that a shared group mental model can be developed.

In a transdisciplinary learning setting, the use of insights as the basis of joint problem framing has formed the foundation of the transdisciplinary “integrated systems and design thinking” methodology.

As opposed to a fact, or a single piece of data, an insight has explanatory power, addressing the “why” or “how” of a situation, rather than only the “what”. Based on observation, insights often also indicate a contraposition in the current understanding that defies intuition and can be explained concisely. Following existing concepts, insights are also explained as being information that restructures previously held assumptions, resulting in an “AHA!” experience for the individual.

The literature provides support for this definition of insight based on these key characteristics:

- Subjectivity: Although a group of people might receive the same piece of information, it is not automatically guaranteed that all of them will arrive at an insight. Insights can also yield a “realization about oneself” that is unique to each individual.

- Suddenness: In contrast to incremental problem solving, where the solver has an estimation on how to solve the problem and reach the solution in an incremental, analytical manner, having an insightful experience can be compared to a light bulb that suddenly switches on.

- Certainty: People who have an insight are confident “that the solution is correct without having to check it”.

- Emotions: People who have insights report positive feelings such as “a jolt of excitement”, but also experience a release of tension in sight of having overcome the experienced impasse.

Components of the insight discovery process

Based on the analysis of the insight diaries we were able to differentiate the insight discovery process into two states and three different phases. These are:

- State 1: Original mental model

The original mental model represents the original state of knowledge before the introduction of any new experiences or information.- Phase 1: Insight trigger

The first phase of the IDP model is the trigger in which an ‘AHA!’ moment occurs. A trigger is caused by the acquisition and incorporation of new pieces of information, both individually as well as collectively (i.e. such as in a group), which challenges the current mental model.

An analogy to a trigger is the concept of activation energy in thermodynamics. In order to initiate a transformation bringing a system to a more stable state, energy is required to “jump-start” the system.

The trigger is information that does not fit into an existing mental model of an individual—leading to cognitive dissonance - Phase 2: Liminal space (including reflection, re-framing and signal processing)

The insight process is also characterized by the presence of a liminal space. In making the decision to leave the comfort zone, one acknowledges the limits of the original mental model. The individual is moving into “unchartered territory” at this point. The process requires time, is challenging and can be associated with contrasting emotions, including those of uncertainty or ambiguity. The need of individuals to feel safe and supported during their time in the liminal space is important.

Three processes are a part of the liminal space:- Reflection: This is the process of questioning, carefully examining and evaluating one’s own assumptions.

- Problem reframing and iteration: This is the process of iteratively re-adjusting one’s assumptions or perspective on a problem situation or topic. Reframing occurs when individuals conclude that their original mental model (i.e. assumptions and beliefs) has become inadequate for understanding a problem situation or topic.

- Signal processing: This is the means by which individuals try to make sense of the external ‘signals’ the individual is exposed to while they are in the liminal space and making the shift between the original and the adapted mental model.

- Phase 3: Insight formulation

The third phase of our model is the formation of an insight—this is a moment of clarity and new-found understanding, which leads to a shift in an individual’s mental model. This phase is often characterized by a strong positive feeling of accomplishment and concludes with the formulation of knowledge that is understood and shareable by the individual. The formation of an insight is comparable to a threshold concept.

- Phase 1: Insight trigger

- State 2: Adapted mental model

Once an insight has formed, individuals enter a new state of knowledge. With a formed insight, the individual is able to apply and adapt their new knowledge. In this phase participants have an adapted mental model of the problem space, that incorporates the insight(s) gained.

“It is exactly this discomfort that opens room for new insights— leaving your comfort zone as a crucial prerequisite for learning processes”

Traditionally, institutions of higher education have been organized around providing students with the competences to succeed in individual disciplines rather than to have the capacity to solve problems in the real world. However, there is growing recognition that higher education should impart both skills needed for conducting high quality research, as well as for solving wicked sustainability problems in our societies.

In this article, we argued that insight discovery is a key competence for:

(i) conducting inter- and transdisciplinary research;

(ii) eliciting transformative learning; and

(iii) addressing wicked problems and societal dilemmas.

Despite being a very subjective experience, insight discovery processes do not take place in a vacuum and need to be understood in relation to their physical and/or group settings. Hence, insight discovery can be enabled or hindered through external factors. For instance, creating a safe environment to share new ideas, providing sufficient space to explore different points of views and encouraging people to go beyond their current mental model with the help of different tools and methods are conducive for an insight discovery process. These external factors can then facilitate leaving fixation and arriving at a new, adapted mental model.

We believe that by providing a clear IDP model and showing the integrative and transformative potential of insights, this article can support other transdisciplinary researchers and instructors in enabling insight discoveries in their own projects, programmes or university courses.