“Contextualizing predictive minds” discusses how the structure of human memory seems to be optimized for efficient prediction, planning, and behavior.

We propose that these capacities rely on a tripartite structure of memory that includes concepts, events, and contexts—three layers that constitute the mental world model.

We suggest that the mechanism that critically increases adaptivity and flexibility is the tendency to contextualize. This tendency promotes local, context-encoding abstractions, which focus event- and concept-based planning and inference processes on the task and situation at hand. As a result, cognitive contextualization offers a solution to the frame problem—the need to select relevant features of the environment from the rich stream of sensorimotor signals.

We draw evidence for our proposal from developmental psychology and neuroscience. Adopting a computational stance, we present evidence from cognitive modeling research which suggests that context sensitivity is a feature that is critical for maximizing the efficiency of cognitive processes.

Finally, we turn to recent deep-learning architectures which independently demonstrate how context-sensitive memory can emerge in a self-organized learning system constrained by cognitively-inspired inductive biases.

Long-term memory can be viewed as a particular kind of contextualized model. Our argument is that due to the large quantity of both available sensory information and potential environmental interactions, a central challenge for our brain lies in the selective activation of only those model components that are relevant for the current task at hand—or a small set of tasks that are unfolding in parallel when multitasking. The crux lies in the frame problem, that is, in the problem of knowing what is relevant without effortful computations.

To solve the frame problem, our brain appears to learn to flexibly generalize away from the sensorimotor data and learn a compressed contextualized world model.

Beyond the frame problem, the ultimate purpose of the model is to facilitate flexible, adaptive (including compositional), and efficient human behavioral decision making and control of environmental interactions in a task- and goal-oriented manner.

On the longer-term, inference leads to the development and adjustments of long-term memory. It generalizes and abstracts the developing world model, selectively memorizes episodic, contextualized experiences, and learns and optimizes behavioral policies.

On the shorter time scale the here-and-now is processed. In this case, active inference processes determine (i) current perceptions and (ii) attention and motor behavior. Perceptions integrate incoming sensory information inferring context as well as, within the inferred context, concepts and events. Attention and motor behavior are controlled prospectively in a goal-oriented manner.

We maintain that active inference is guided by a set of phylogenetically-optimized, innate inductive biases that have pre-structured our brain, its developmental pathway, and the unfolding neurobiological dynamics.

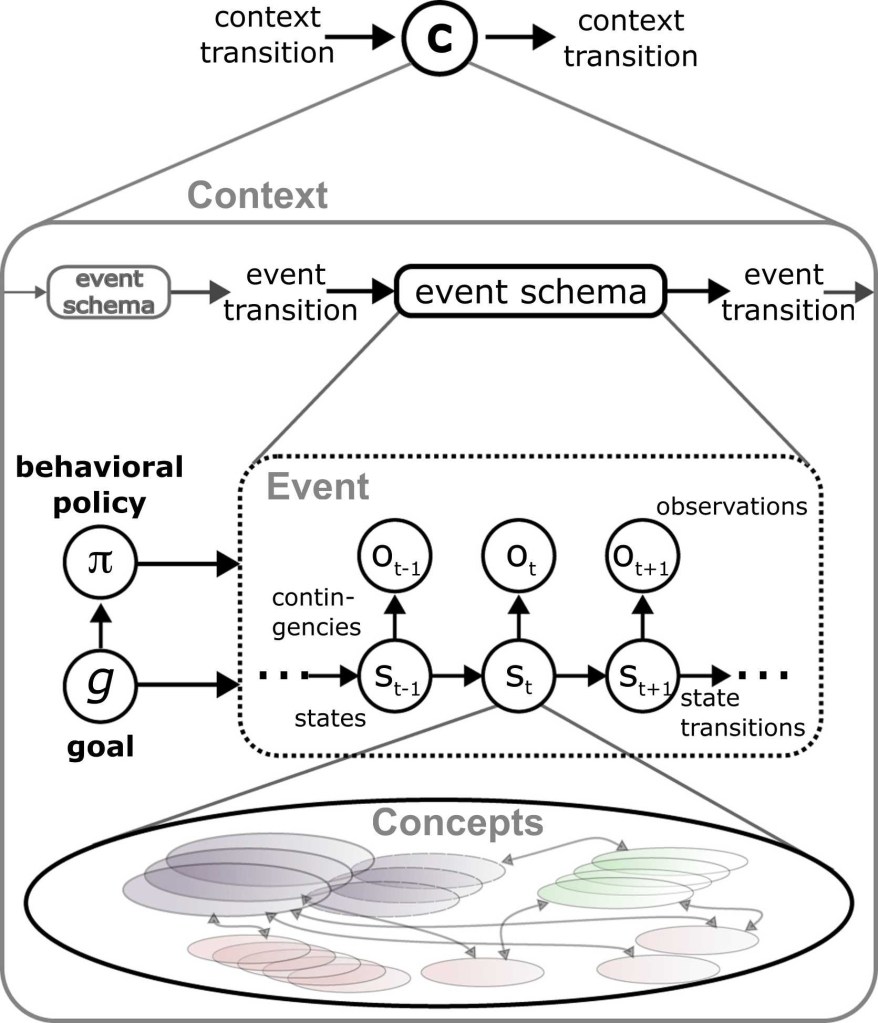

Bottom: A distributed network of instantiated concepts and prior concept activities constitutes the concept encoding level of a state of mind.

Middle: An event (schema) expression (dashed box) yields a network of event-constituting concept instantiations including entities, properties, and relational concepts as well as representations of the currently unfolding dynamical changes of these concepts. Behavioral policies π co-determine the dynamic event progressions over time, dependent on the currently active, task-inferred goals g. The addition of conditions when an event may commence and how long it may unfold (not shown), leads to the encoding of event schemata. Event schema expressions are temporally sequentialized, offering potential episodic memory content.

Top: The inferred context c sets priors over events and concepts. Event progressions and potential context switches are co-inferred via an additional episodic memory loop, which supports selective, active inference-driven planning and reasoning on context-relative, event-schematic levels.

The developing hierarchical world model consists of three fundamental levels: concepts, events, and contexts.

Two further complementary processes appear crucial for memory consolidation and stream-lining behavioral decision making: an episodic processing loop and policy optimization.

In the brain, an episodic processing loop seems to exist complementary to the developing hierarchical world model.

This loop enables the memorization and selective recollection of contextualized episodic experiences, offering not only an immensely useful replay buffer but also the computational means to plan and reason in an extended, episode-oriented, temporal manner. Behavioral policy optimization encourages the context- and goal-conditioned optimization of behavioral routines.

Predictive coding suggests that our brains develop generative predictive world models with the purpose of supporting the invocation of flexible behavior via active inference. While the predictive view of the mind had gained momentum at the turn of the last century, its roots reach much further back into the history of cognitive science as predictive coding integrates both the ideomotor principle and Helmholtz’ idea of ‘unconscious inductions’ (1867).

Active inference is a process-oriented derivative of predictive coding and the free energy principle. Generally speaking, the free energy principle formalizes that an organism has the inherent goal of maintaining internal homeostasis, which corresponds with the objective to minimize anticipated free energy given homeostatic goal states. Following the free energy principle, we differentiate between long-term and short-term active inference processes.

Within the active inference framework and given homeostatic future states, both perception and behavior become task- and goal-oriented. Shorter-term inference processes that are repeated many times will undergo behavioral policy optimization. As a result, behavioral routines and habits form.

As long- and short-term inference processes naturally feed back onto each other, they need to balance a trade-off between learning models that are very detailed, increasing accuracy but reducing generalizability, or very abstract, decreasing accuracy but increasing generalizability.

Knowledge about the world is encoded in long-term memory. The memory can be broadly partitioned in a generative world model, procedural competencies in the form of behavioral policies, and its autobiographic, episodic memory.

The world model contains semantic and factual knowledge an agent has inferred so far. For adaptive flexible behavior to be possible, the model should support predictions at various time-scales and levels of abstraction. For example, it should be possible to selectively instantiate contexts with rather narrow representations—as when fully focusing on cleaning one particular object, like a chess piece—or rather broad contexts—as when thinking about what type of board game to play.

As a result, the world model should enable the selective invocation of sparse targeted predictions about those aspects of the environment that are believed to be vital for the current task.

This challenge can be met in a system that is structured hierarchically into concepts, events, and contexts.

We have thus sketched out a framework, which effectively facilitates the efficient invocation of highly adaptive behavior.

Due to the bias to contextualize its actively predictive mind, concept-event-context-structured long-term memory develops. The memory structures include

(i) a developing semantic world model, which is hierarchically structured into concepts, events, and contexts,

(ii) procedural knowledge in the form of context-conditioned behavioral policies, which streamline covert attention as well as overt motor behavior, and

(iii) episodic memory.

Active inference processes within the developing model are inherently task- and goal-directed. They shape the developing model structure dependent on the so-far developed model and its bias to infer contexts first and context-focused, context-relative events and concepts second. To further focus behavioral inference on those behaviors that have been successful in previous similar contexts and given similar goals, context-relative behavioral policies are learned. An episodic memory loop supports the contextualized selective optimization of behavioral policies as well as the generalization and compaction of the developing world model. The loop also supports active planning and reasoning by considering alternative sequences of contextualized events.

The interdisciplinary research provides evidence on how our brains might inductively learn progressively more elaborate long-term memory structures.

Model learning biases and hierarchical concept-event-context information processing biases conjointly with active-inference-based planning, decision making, and behavioral control interactively bootstrap inductive learning.

The interdependence effectively balances model learning, policy learning, the formation of episodic memory, and behavioral inference effort.

As a result, progressively more effective, contextualized models and involved cognitive and behavioral policies develop.

A contextualizing world model, contextualized behavioral policies, plus a context-relative episodic memory loop may thus offer an explanation of how our mind solves the long-standing frame problem in AI, that is, the problem of being able to flexibly decide on what is task-relevant at any point in time.

Combined with task-oriented active inference processes, we expect that the resulting cognitive architecture will be able to model human-like cognitive development as well as human-like planning, reasoning, and decision making abilities. Endowed with larger cognitive processing capacities, possibly even human-superior but still human-compatible reasoning and problem solving may become possible.

The challenge is wide open to design the sketched-out system; that is, a cognitive system that learns semantic knowledge structures that enable the flexible invocation of concept-event-context orchestrations via inference processes.

The orchestrations essentially both interpret the environment and effectively prepare environmental interactions.

Evolution has solved this challenge to a certain extent. We hope that this review is a step toward solving this challenge with artificial cognitive models.