“The adaptive value of stubborn goals”

- Humans show strong attachment to goals they have selected.

- While often framed as a maladaptive bias, we outline three adaptive functions leading to stable goals:

efficient cognitive resource allocation,

shielding from interference, and

scaffolding motivation in the absence of immediate and tangible reward signals. - These considerations shape the algorithmic architectures that support naturalistic goal pursuit, such as the mechanisms that select, implement, and revise goals.

- Understanding how these different mechanisms become miscalibrated may have important implications for characterising alterations in goal commitment affecting mental health.

Humans exhibit a striking tendency to persist with chosen goals. This strong attachment to goals can often appear irrational – a perspective captured by terms such as perseverance or sunk-cost biases.

In this review, we explore how goal commitment could stem from several adaptive mechanisms, including those that optimise cognitive resources, shield decisions from interference, and scaffold motivation in the absence of accessible reward signals.

We propose that these computational considerations have important implications for algorithmic architectures supporting decision making, including separate algorithms for goal selection and implementation, and for monitoring ongoing goals versus alternative sources of reward.

Finally, we discuss how a variety of mechanisms supporting goal commitment and abandonment could relate to dimensions affected in mental health.

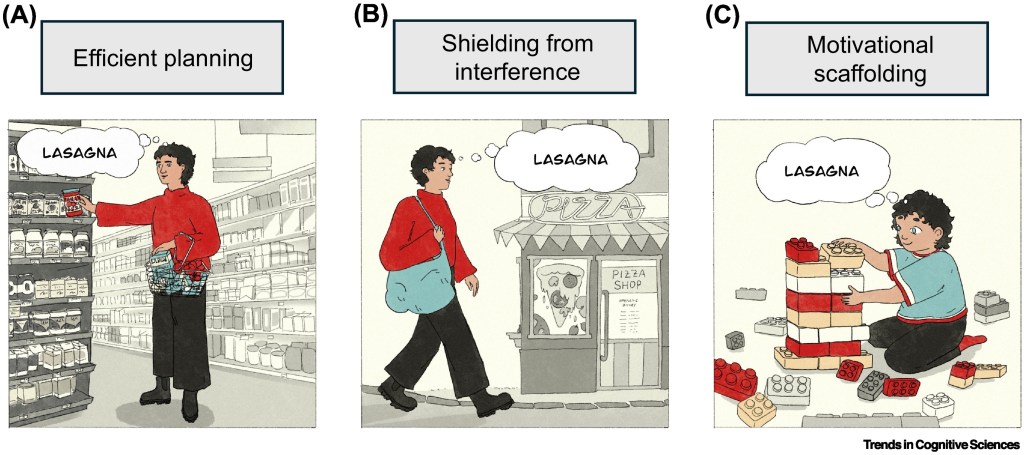

(A) Goal commitment could arise from efficient use of cognitive resources – for example, allowing cognitive resources to be used for implementing the goal (e.g., shopping for lasagna ingredients), rather than continuously deliberating about alternative goals (e.g., when faced with ingredients for other possible recipes).

(B) Mechanisms that limit reconsideration of alternative options after goal selection may help insulate decision making from transient fluctuations in preferences, for example, the short-term temptation of getting a take-out. These mechanisms could shield long-term goals from interference while leading to goal commitment.

(C) Beyond their role in constraining the space of options, goal selection can generate motivational signals that could shape behaviour in the absence of external rewards. This would lead to stable goals by making pursuit of the goal intrinsically valuable. For example, the motivation to complete self-imposed goals during play – such as a child carefully assembling a Lego lasagne – could promote learning and exploration. In turn, this ‘scaffolding’ role of goals extends into adulthood, particularly when the connection between behaviour and the target outcome requires support through an intermediate reward signal.

Humans have the extraordinary capacity to be captivated by the goals we choose. This often manifests as a strong reluctance to abandon goals – even in the face of high costs or better alternatives. Rather than viewing this tendency as a maladaptive bias, we suggest it reflects an adaptive set of mechanisms that solve key computational challenges. Stable goals may stem from optimisation of cognitive resources, shielding long-term goals from interference, and scaffolding complex behaviour in the absence of basic reward signals. Considering these adaptive functions will be key to developing algorithmic models capturing the central role of goals in decision making. In turn, characterising the different ways these processes could be miscalibrated will provide crucial insights for understanding disruptions of goal commitment affecting mental health.