“The coevolution of cognition and sociality“

Cognition serves to resolve uncertainty.

Living in social groups is widely seen as a source of uncertainty driving cognitive evolution, but sociality can also mitigate sources of uncertainty, reducing the need for cognition.

Moreover, social systems are not simply external selection pressures but rather arise from the decisions individuals make regarding who to interact with and how to behave. Thus, an understanding of how and why cognition evolves requires careful consideration of the coevolutionary feedback loop between cognition and sociality. Here, we adopt ideas from information theory to evaluate how potential sources of uncertainty differ across species and social systems. Whereas cognitive research often focuses on identifying human-like abilities in other animals, we instead emphasize that animals need to make adaptive decisions to navigate socio-ecological trade-offs.

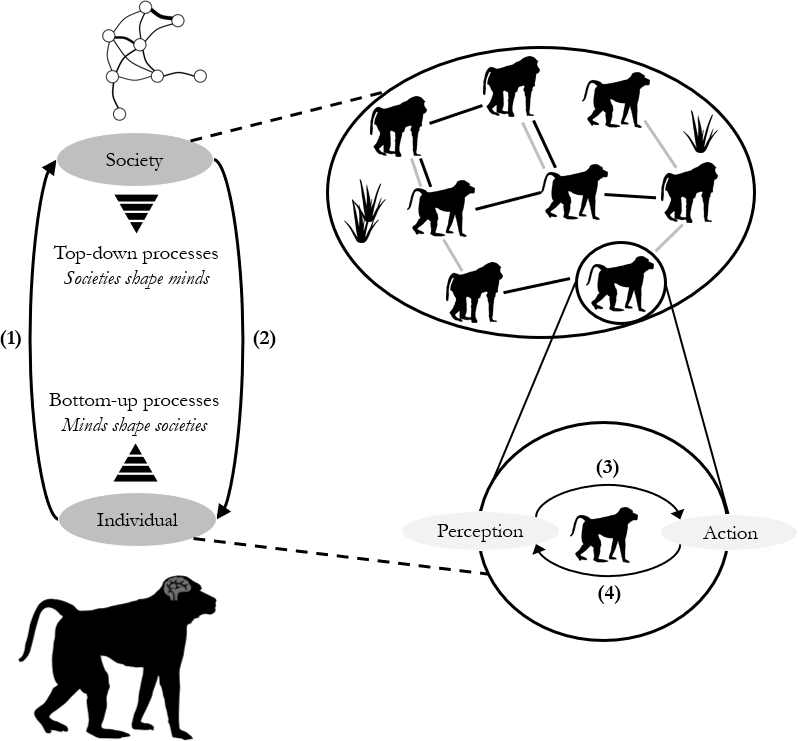

These decisions can be viewed as feedback loops between perceiving and acting on information, which shape individuals’ immediate social interactions and scale up to generate the structure of societies. Emerging group-level characteristics such as social structure, communication networks and culture in turn produce the context in which decisions are made and so shape selection on the underlying cognitive processes. Thus, minds shape societies and societies shape minds.

Minds shape societies via bottom-up processes (arrow 1), and societies shape minds via top-down processes (arrow 2). Societies can be conceptualized as social networks of interactions between individuals in different contexts, such as grooming or mating (symbolized by lines between individuals, with colours representing different social contexts). The social network provides the context for and is shaped by individual decision-making. Individual decision-making unfolds through a perception–action feedback loop (arrows 3 and 4) by which individuals use and update their knowledge to increase their payoffs. Individual decisions and group outcomes (e.g. social structure) are embedded in and influenced by external ecological factors, such as resource availability and distribution.

The traditional perspective that social life is intrinsically ‘difficult’ and requires cognitive solutions is beginning to give rise to a view considering the coevolutionary interplay between sociality and cognition.

However, perhaps because of the nature of bidirectional causation, progress in understanding the role of social factors in cognitive evolution still lags behind that of external selection pressures.

For instance, this special issue showcases the great progress that has been made in unravelling cognitive solutions to foraging problems, like trap-lining in butterflies and spatial memory for cached food in chickadees.

Research, including work on facial recognition in wasps and cleaner–client mutualisms in fish, highlights the potential for similar progress in the social domain, but major questions remain. Below, we outline some outstanding questions and how they may be addressed in the future.

(a) How does social life modulate uncertainty?

To understand the social sources of uncertainty that influence cognitive evolution, we must identify what decisions animals need to make and what information-processing abilities are required. Rather than grounding research in anthropocentric assumptions of what humans do, we advocate the use of tools, such as playbacks and automated experiments to manipulate the outcome of social interactions and the value of social partners. By simulating changes in the dynamics of a biological market, researchers can then evaluate what information animals attend to and act upon to resolve social uncertainty.

(b) What is the adaptive value of cognition in resolving social uncertainty?

Many correlational studies indicate that individuals that form and maintain strong social relationships gain fitness benefits. However, the causal basis of these links, and whether they are underpinned by cognitive processes, remains unclear. Do individuals that are better socially integrated obtain such positions by means of their social cognition? If so, could individuals with socio-cognitive abilities that occupy central social positions also excel at other fitness-relevant tasks, such as foraging and

predator avoidance, confounding the relationship between social integration and fitness? To address this, we must integrate research on the adaptive value of sociality and cognition. For instance, long-term monitoring of natural populations can help to reveal the degree to which social traits (e.g. network centrality or dominance) are shaped by information gained from experience throughout development. Moreover, as experimental studies of social decision-making commonly reveal

substantial variation in individual performance, there is ample scope for work linking this variation to its fitness consequences.

Studies focusing on how animals resolve trade-offs (e.g. between long-term investment in social partners versus short-term gains of social plasticity) will provide important advances.

(c) What are the bottom-up effects of individual decisions on emergent social structure?

To understand bottom-up effects, an important focus will be to address how (variation and plasticity in) individual decisions can give rise to social structure. By better understanding how individual decisions shape social structure, we will better understand how individuals’ actions affect both their and conspecifics’ exposure to uncertainty. Natural ecological events

(e.g. extreme weather), changes in group composition and experimental manipulations can also offer valuable opportunities to establish how decision-making affects the re-configuration of networks following disturbances. Here, advances in social network analysis will be essential, enabling explicit investigation of how individual actions drive dynamic changes in network structure.

(d) How do (emergent) group-level properties arise and shape selection on individual decision-making?

Understanding the evolution of social traits (and the cognitive processes underpinning them) is complicated by the fact that individuals’ phenotypes depend not only on their own genotypes but also on those of their social partners. Recent advances in quantitative genetic modelling now allow us to determine genetic variance in, and covariance among, individual cognitive and sociability phenotypes (e.g. dyadic bond strength and social network positions) and estimate direct and indirect contributions to fitness. In tandem with ongoing improvements in quantifying individual cognitive variation, such approaches will help us to understand how the structure of social networks influences the direction and strength of selection. Meanwhile, formal theoretical modelling will be invaluable to understand long-term evolutionary dynamics, as it forces us to be explicit in our assumptions and enables investigation of coevolutionary dynamics that are difficult to observe directly.