Social learning is complex, but people often seem to navigate social environments with ease.

This ability creates a puzzle for traditional accounts of reinforcement learning (RL) that assume people negotiate a tradeoff between easy-but-simple behavior (model-free learning) and complex-but-difficult behavior (e.g., model-based learning). This publication offers a theoretical framework for resolving this puzzle: although social environments are complex, people have social expertise that helps them behave flexibly with low cognitive cost.

Specifically, by using familiar concepts instead of focusing on novel details, people can turn hard learning problems into simpler ones. This ability highlights social learning as a prototype for studying cognitive simplicity in the face of environmental complexity and identifies a role for conceptual knowledge in everyday reward learning.

- Social interactions present complex learning challenges.

- Recent computational models of learning assume people negotiate a tradeoff between complex-but-difficult behavior and easy-but-simple behavior.

- Humans have social expertise that lets them simplify difficult learning problems, reducing detailed scenarios to familiar social concepts that can subsequently guide learning.

- People can therefore use learning strategies that achieve flexible social behavior with easy cognition, using the earlier work of concept development to simplify the later work of complex choice.

- Accounting for pre-existing conceptual knowledge and expertise can enrich models of reinforcement learning in familiar environments.

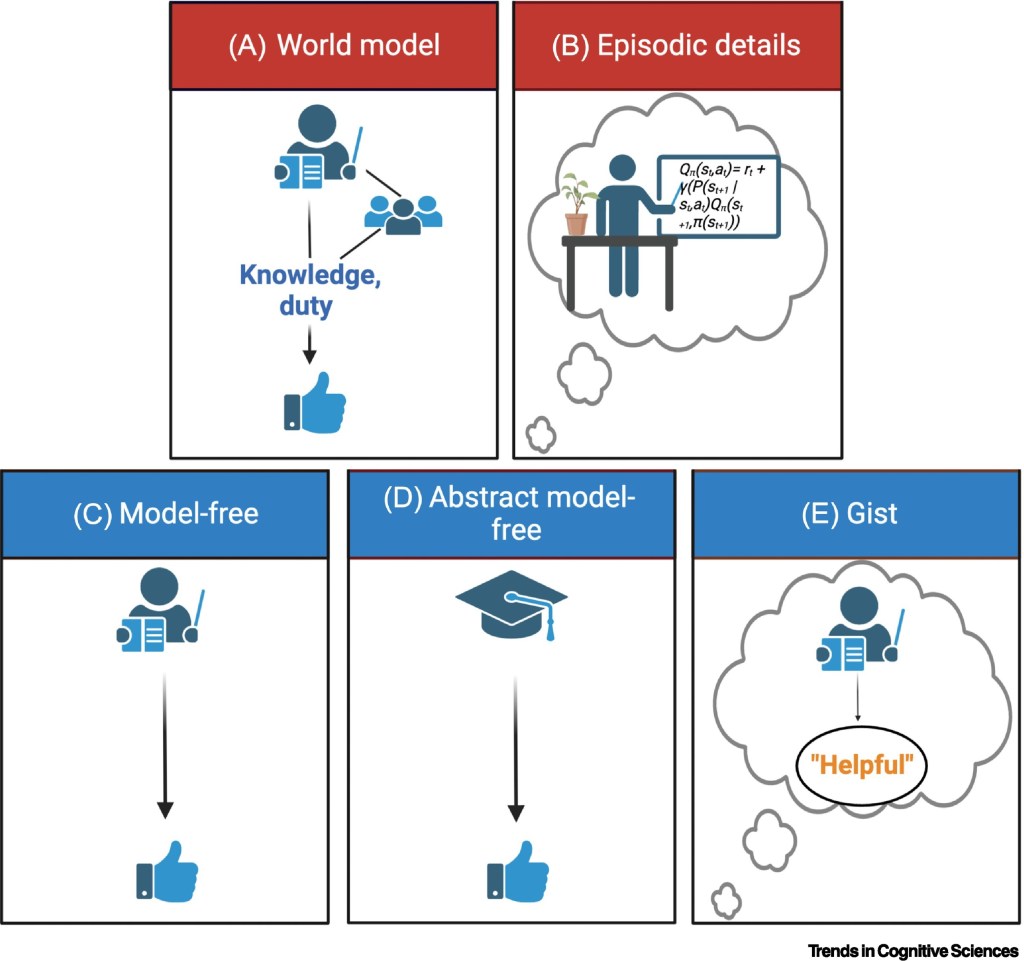

In this example, a student approaches Dr Smith’s office and experiences illuminating help, providing a rewarding experience. (A) To achieve complex behavior, a learner could use a model of the world, instantiated in a cognitive map, that specifies Dr Smith’s role in the class in relation to students and/or that specifies a causal model explaining why approaching Dr Smith will lead to reward. By using this cognitive map, a student can generalize to a new professor (Dr Jones), recognizing that a new professor occupies the same role and will lead to the same outcomes.

(B) Through episodic memory, the student could encode details of the exact interaction in which they received help. By later retrieving these details, they can make flexible choices based on any features present in the interaction.

(C) In traditional model-free learning, the student associates Dr Smith with reward. This learner would not generalize to new choices, such as visiting Dr Jones.

(D) Through social expertise, a student could use an abstract representation of ‘approach the professor’ and learn this action yields reward; this learning can be model-free, with no consideration of why the professor led to reward. Such a learner could generalize with low cognitive effort to a new individual categorized as a professor.

(E) Through expertise, the student could encode an abstract representation of a specific interaction with the professor, reducing details to a gist summary indicating the professor was helpful. The student could generalize this simpler representation to a diverse array of new situations, such as asking the professor for help fixing a broken bicycle or asking for a letter of recommendation.

Social learning is complex.

Traditional accounts suggest people must either follow simple model-free reward contingencies or pay a cost to use flexible learning computations.

Although people use these strategies, humans also have social expertise that can simplify learning problems, allowing flexible behavior with low cognitive cost. People effortlessly and spontaneously recognize abstract social concepts that describe roles (mentor, helper), behaviors (generous, competent), and other social patterns.

These concepts reflect semantic knowledge, representing generalized abstract relationships without retrieving specific details.

People can use pre-compiled abstract concepts to facilitate planning, associate abstract social roles with model-free reward, or encode the gist meaning of an interaction, allowing them to generalize reward and make adaptive choices with cognitive ease. Although these strategies cannot replace every kind of complex social learning, they can support flexible behavior through simple cognition in familiar settings, complementing more elaborate learning. However, people risk automatically mapping new situations to familiar abstractions even when they are not optimal, posing a limit to flexibility.

This framework demonstrates how RL supports complex social behavior, bridging social cognition with computational principles of RL. While this proposal applies to any domain where humans have expertise, social interaction offers an informative test case; although not all humans are chess or bird experts, nearly all humans have social expertise and must navigate complexities of social interaction.

Social learning can thus serve as a prototype for studying how people navigate complex everyday environments, building a bridge for future research between the study of concept development and the study of adaptive choice.