“The illusion of information adequacy“

“The science behind why people think they’re right when they’re actually wrong“

You don’t know what you don’t know.

–Socrates

How individuals navigate perspectives and attitudes that diverge from their own affects an array of interpersonal outcomes from the health of marriages to the unfolding of international conflicts. The finesse with which people negotiate these differing perceptions depends critically upon their tacit assumptions—e.g., in the bias of naïve realism people assume that their subjective construal of a situation represents objective truth.

The present study adds an important assumption to this list of biases: the illusion of information adequacy.

Specifically, because individuals rarely pause to consider what information they may be missing, they assume that the cross-section of relevant information to which they are privy is sufficient to adequately understand the situation.

Participants in our preregistered study (N = 1261) responded to a hypothetical scenario in which control participants received full information and treatment participants received approximately half of that same information. We found that treatment participants assumed that they possessed comparably adequate information and presumed that they were just as competent to make thoughtful decisions based on that information.

Participants’ decisions were heavily influenced by which cross-section of information they received.

Finally, participants believed that most other people would make a similar decision to the one they made.

We discuss the implications in the context of naïve realism and other biases that implicate how people navigate differences of perspective.

There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.

–Donald Rumsfeld

Anecdotally, friction between parties holding divergent perceptions seems particularly prevalent in today’s world—clashes over vaccines, abortion rights, who holds legitimate claims to which lands, and climate change surface in the news regularly. Conflicts on social media, between passengers and flight attendants, and among parents and referees at children’s sporting events seem equally common. Correspondingly, the need to ascertain the various causes of poor perspective taking feels particularly acute at present.

Naïve realism offers one clear explanation of how our default assumptions can derail our attempts to understand others’ perspectives. We complement this line of research by proposing that a second major contributor to misunderstanding the perspectives of others is the illusion of adequate information.

This study provides convergent evidence that people presume that they possess adequate information—even when they lack half the relevant information or be missing an important point of view. Furthermore, they assume a moderately high level of competence to make a fair, careful evaluation of the information in reaching their decisions.

In turn, their specific cross-section of information strongly influences their recommendations.

Finally, congruent with the second tenet of naïve realism and the false consensus effect, our participants assumed that most other people would reach the same recommendation that they did.

We interpret our results as complementing the theory of naïve realism by illuminating an important, additional psychological bias that fuels people’s assumption that they perceive objective reality and potentially undermines their motivation to understand others’ perspectives.

“Our brains are overconfident that they can arrive at a reasonable conclusion with very little information,”

— Angus Fletcher

How might greater doubt or humility facilitate the understanding and appreciation of others’ perspectives?

We suspect that in many real-world situations individuals rarely pause to consider how complete their picture of a situation is before passing judgment. Comedian George Carlin’s observation—that, relative to our driving, slower drivers are idiots and faster drivers are maniacs—is often invoked in discussions of naïve realism.

Although people may not know what they do not know, perhaps there is wisdom in assuming that some relevant information is missing.

In a world of prodigious polarization and dubious information, this humility—and corresponding curiosity about what information is lacking—may help us better take the perspective of others before we pass judgment on them.

“It’s not just that people are wrong.

It’s that they are so confident in their wrongness

that is the problem,”The antidote is

— Barry Schwartz

“being curious and being humble.”

The fact that the people in the study who were later presented with new information were open to changing their minds, as long as the new information seemed plausible, was encouraging and surprising, the researchers and Schwartz agreed.

“This is reason to have a tiny bit of optimism that, even if people think they know something, they are still open to having their minds changed by new evidence,” Schwartz said.

In the context of this research, I would like to repeat and would stress the importance of

- being humble and show the needed intellectual humility, to avoid failure, allowing “playful” decision making, to support the missions defined, and be curious

- The quote in the article refers to the unknown unknowns.

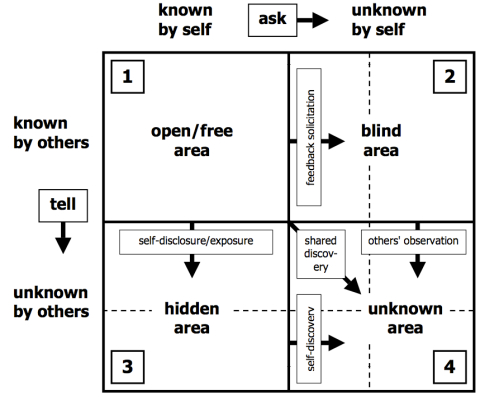

However, from experience and literature, the Johari Window exposes an even more interesting quadrant, open for simple improvement, related to the conclusion of this research:

Known Unknowns, – Blind Spots, – “ask for feedback“.