In many careers, a person must learn foundational skills before advancing deeper into their profession. Computer programmers need a solid foundation in basic mathematics; nurses must gain clinical experience and specialized training to become nurse practitioners; a negotiator’s ability to persuade depends on solid communication and active-listening skills.

A recent paper published in Nature Human Behaviour mapped the dependency relationships between workplace skills using data from millions of job transitions and U.S. workplace surveys. The authors identified a nested structure in many professions, where advanced skills depend on prior mastery of broader skills. This nestedness, they found, has significant implications for wage inequality and career mobility in increasingly complex labor markets.

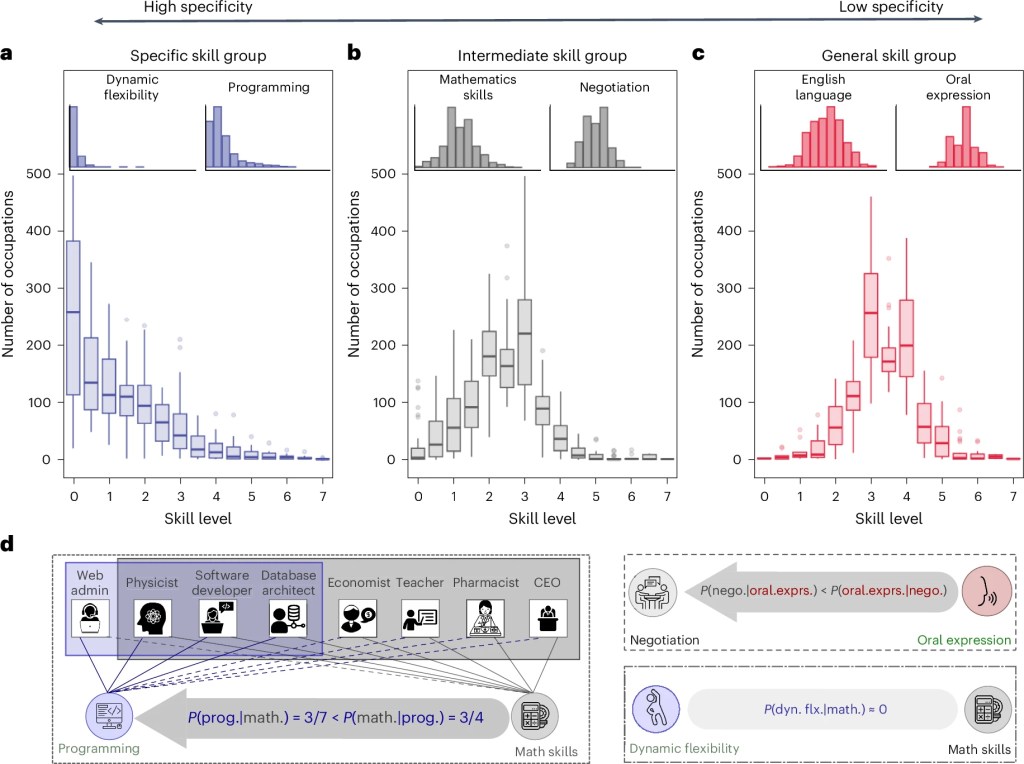

The box plots display the data range, with the boxes representing the interquartile range, the central line indicating the median and the whiskers extending to the minimum and maximum data points within the interquartile range. Skills are categorized on the basis of the characteristic shapes of their level distribution across occupations, exemplified by the insets. These categories are labelled as general (31 skills), intermediate (43 skills) and specific (46 skills), with an arrow at the top indicating increasing specificity from right to left. The skewed distribution shapes (blue on the left) peak at zero; that is, most occupations require little or no proficiency in these skills, and only a few require advanced levels. As we move general skills (red on the right), the distribution shifts towards the higher levels, indicating that a wide range of jobs require high proficiency in those skills. d, A schematic illustrating our inference method for dependency between skill pairs using the asymmetric conditional probability in job requirements—one skill being required given that another is. For example, if math skill is more likely needed given the presence of programming in occupations (compared with the reverse), p(skillmath∣skillprogram) >> p(skillprogram∣skillmath), we infer a directional dependency: math → programming, weighted by the level of asymmetry. Similarly, oral expression → negotiation, but math

↛ dynamic flexibility, as rare and independent events are filtered out.

“We found that many skills aren’t just complementary — they’re interdependent in a directional way, acting as prerequisites for others, snowballing layer over layer to get to more specialized knowledge.” says Moh Hosseinioun, a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University and lead author of the study.

The study grew out of a question about how the classifications of blue-collar and white-collar jobs arise, says SFI External Professor Hyejin Youn (Seoul National University), a corresponding author on the study. “In trying to answer this question, we found that these categories emerge around specialization.” Knowledge-based work tends to require more time to build specialized skills while physical work is often learned on the job.

“It’s like a succession model in ecology — acquiring complex skills requires a sequence of prerequisites,” Youn explains. Just as predators depend on prey, which rely on vegetation, which in turn requires soil created by microbes and fungi breaking down rock, cognitive development unfolds in layers within a kind of mental ecosystem. “Advanced problem-solving — like solving partial differential equations — first depends on mastering arithmetic, understanding mathematical notation, and grasping logical principles,” she says. “Basic educational skills are the cognitive equivalent of early organisms, creating the conditions in the mental ecosystem for higher-order reasoning to emerge, and are essential for developing the advanced skills that can lead to higher wage premiums.”

This job skills structure isn’t itself all that surprising, write the authors in a supplemental research briefing, but it has significant societal implications. “We find that skills that are more closely aligned with the nested hierarchy require a longer education, command higher wage premiums and are less likely to be automated,” they write.

c–e, Reachability (that is, arrival probability) from each skill to programming (c), negotiation (d) and repairing (e) (highlighted). Dark hues indicate a higher likelihood of arriving at the focal skill. Contrary to the well-nested programming and negotiation, repairing does not predominantly rely on general skills, indicating its unnested nature.

The nested structure in job skills has become more pronounced over the past two decades, suggesting a possible increase in job polarization as longer, deeper, and more complex sequences of prerequisites may hinder newcomers. Policy interventions may be needed to avoid increasing inequality and polarization in the job market; those unable to access education for foundational skills face barriers to entering higher-wage career paths. “The more we become specialized and nested, the more inequality and disparity across the labor market will occur,” says Youn.

The findings also have implications for education policy. Quick “reskilling” programs may have limited effectiveness without investment in general foundational skills, and moves by universities to remove foundational courses in favor of immediately applicable skills could have unintended consequences for graduates.

The findings also raise concerns about using AI to tackle problems that require foundational skills. “Large language models are unprecedented in how they target fundamental skills,” says Hosseinioun. “Is this an opportunity, where some of the layers of the hierarchy might be condensed? Or, if we outsource those fundamental skills, will we become unable to learn more advanced skills?”

The more our collective knowledge base grows, the harder it becomes for any one individual to master a universal set of skills. Our modern economy’s demands for ever-more-specialized skills is shaping broader social and economic systems, and the highest-paying skills are locked within a series of prerequisites.

“These structured pathways systematically shape professional development and the socio-economic landscape, driving differences in rewards and career accessibility based on early choice of skill acquisition,” write the authors. “This deeper nested structure imposes greater constraints on individual career paths, amplifies disparities and has macroeconomic implications, affecting the resilience and stability of the entire system.”

Read the study “Skill dependencies uncover nested human capital” in Nature Human Behaviour (February 24, 2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-024-02093-2

Original blog post copied from SFI:

https://santafe.edu/news-center/news/nested-hierarchies-in-job-skills-underscores-importance-of-basic-education